[scroll down for polish version / polska wersja językowa poniżej]

A few weeks ago, I had the pleasure to visit the studio of Paulina Tyro-Niezgoda, who is a young exhibition designer. She invited me to the attic of a building situated in a picturesque location, right at the Warsaw New Town market square. In our conversation she explained to me the nuances of work of an exhibition designer, elaborated on the role the studio plays in her daily work and told me the story of this extraordinary place which was previously used by her grandmother, Barbara Pisarczyk-Niezgoda.

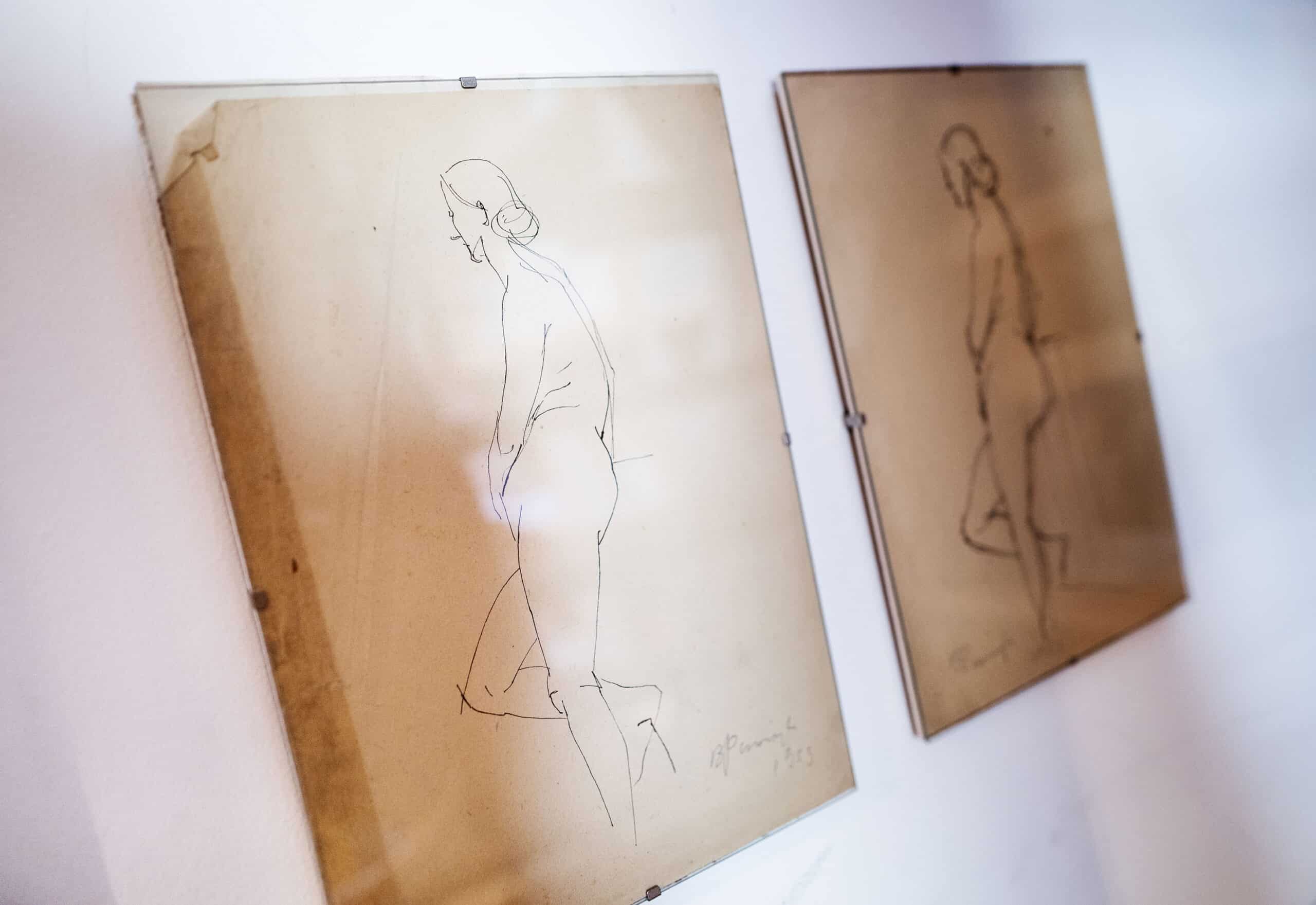

Art Studio of Paulina Tyro-Niezgoda, photo by Michał Korta

Patrycja Głusiec: Generally speaking, space plays an extremely important role in your work. I am wondering what is the specific function of your studio in your activities.

Paulina Tyro-Niezgoda: I heard a similar question from Professor Andrzej Dłużniewski, as he asked it to us, students. At that time he taught classes at The Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. I said then that my studio was like a case for me. My silhouette was impressed in this place. I still feel the same way.

PG: Let’s go into detail. Your studio is located within the Old Town in Warsaw, which is the area that attracts thousands of tourists. Nonetheless, your presence, the studio itself and how different generations of artists are connected through it prove that this part of our capital city is also offering a lot to its residents. Could you tell us something about the history of this Warsaw historic art studio?

PTN: It all started in 1982 when Barbara, my grandmother, who was a painter, was alloted an apartment which she could adapt for her workplace. Times were so much different and so interesting… Could you even imagine that large numbers of art studios are set up in council buildings right now? The area of the Old Town was just one of several areas in the city which boasted quite a significant number of such spaces. Most of the studios were located in the attics of tenement houses. It was just a building shell when our family was offered this space for use, with no wiring, plumbing and heating, there were even some pigeons flying inside. We had to decorate it to make it fit for its purpose. The interior had been changing virtually all the time for the next 30 years. Decorating the studio was no mean feat, it required resourcefulness and creativity, just like any other endeavour in the Polish People’s Republic. Also my parents started to carry out projects and follow their passions for architecture and design at the same studio. I think that this determined the need for a long-term transformation of these interiors and made the space malleable. The rooms acquired new functions, their shapes changed, some characteristic features were added or removed. In my opinion, the alterations were supposed to make the space more comfortable for its users. Those working here spent a lot of time inside so, unsurprisingly, the studio gradually became their second home. There were, however, some changes that I regret. There used to be incredible, long, ribbed radiators from a factory. They were removed because the building administrator wanted to modernize the heating system and make all relevant equipment uniform. Therefore, we can say that this change was induced by an external factor. When it comes to the photography studio which used to be in here, we got rid of it ourselves. It probably seemed at that point that analog photography was the thing of the past and nobody would be interested in it anymore.

PG: Why and how did your grandmother start to use this studio?

PTN: She was offered this opportunity because such was the city council policy at the time. Art studios were opened in different parts of Warsaw, many of them in the Old Town. Some artists received apartments on the ground floor, with easy access by car. Others were given more challenging spaces which had to be “erected” with their own efforts and expenditure. My grandmother got her studio in the year before my birth. Barbara and Paweł, my father, had to choose their studio and were offered this one and five other possible locations. This space seemed the most interesting despite the fact that it needed new heating system and much better lighting. Thirty seven years went by and the new chapter in the history of this studio opened. Barbara passed away in 2019. After her death the transformation of the space into a historic art studio began.

Art Studio of Paulina Tyro-Niezgoda, photo by Michał Korta

PG: Metamorphoses of spaces are very intriguing and this is what you chose to involve yourself in professionally. When a visitor comes to an exhibition, more often than not he does not think about who designed the space where the event is being held. We always think about an artist first, then about a curator. Nevertheless, it is in the hands of an exhibition designer to make the vision of the team working on an exhibition concept come into being. The designer also has an impact on the reception of the exhibition as such. Could you briefly tell us about the process of creating an exhibition and your role in it?

PTN: Organizing an exhibition at an art institution is sometimes quite a long process. It is probably one of its characteristic features. Things do not happen overnight like in other types of business. When a team works on an exhibition it needs time for various arrangements. A designer is an intermediary between the vision of a curator or an artist and the producer.

A designer draws up the whole concept of spatial arrangement and sums it up in a technical dossier which is the cornerstone or a basis for producing an exhibition and allows for pricing and subcontracting its particular constituent parts. The dossier includes a spatial plan which is interconnected with the narration that a curator designed. Apart from that, the dossier specifies where individual works will stand or hang. Their arrangement in space should be in line with defined view axes, which will enhance viewers’ experiences, and should take into account empty buffer space around individual works, so that visitors can interact with each object as a separate entity.

An exhibition design also includes small forms or street furniture and partition walls, which additionally divide space into sections. A designer also selects the colour of the background and other elements, for example the colours of picture frame mouldings. What is more, a designer suggests what display furniture to use, which entails selecting shelves, display cabinets, tables, domes and seats. The project dossier includes technical drawings of all these elements.

In addition, if there are no specific orders by artists, a designer and a curator decide together which video works are going to be screened for the audience and which ones will be made available on other carriers. It is a designer (and a curator) who decides whether sound will be heard in exhibition rooms or whether the soundtracks for videos will only be available through headphones. Will the viewer have an opportunity to sit down or will he rather stand while contemplating a particular work of art.

The designer makes a number of small and big decisions which influence the final appearance of the exhibition space and how the audience interacts with displayed pieces. We try to make these decisions as early in the process as possible. However, it needs to be emphasized that despite big art institutions being perceived as staid, the process of designing an exhibition is actually very dynamic. Changes are frequent when it comes to the selection of works to be displayed, conservator’s recommendations, as well as technical and production details. The whole process is concluded with the ‘assembly feast’, i.e. the time when the whole team has much more tasks to deal with. At this stage problems and solutions materialize spontaneously and some decisions must be made anew. Objects are usually delivered only during the assembly process and this is when we see them for the first time as such, not just in the pictures. This means that when we work on a project we rely on the information provided to us by artists or owners of works we are going to present (for example, they inform us about the sizes of individual works). Surprises like completely other sizes than declared earlier are endless. It also happens that when we create compositions of several works they do not look good against one another in reality, despite the fact that they seemed perfectly matched at the stage of planning. Assembly is the moment when the project assumes its final shape.

“Tamam Shud” exhibition of works by Alex Cecchetti, organized at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art

PG: How does the work of a designer complement the activities of a curator, a restorer and a producer? How important is cooperation between all of them?

PTN: The final effect, so the exhibition, is always the result of negotiations between a designer, a curator, a restorer, a team of technicians, etc. There are, of course, exhibitions prepared without a designer. Sometimes these tasks are fulfilled by a curator, sometimes it is an artist who designs the exhibition himself. I assume that the niche in the job market which allowed this job to be created appeared as a result of an overall specialization trend.

PG: Tell us something more about strategies implemented when designing exhibitions.

PTN: If anyone is interested in displaying strategies, I strongly recommend the publication entitled “Display” by Maria Haussakowska and Ewa Tatar. When it comes to projects themselves, there are two approaches – transparency and, let’s call it, distinctiveness.

A transparent project will not be noticeable. The exhibition will be well organized in terms of spatial arrangement and functionality and nobody will even reflect on the design as such.

A distinctive project, on the other hand, may interfere with displayed pieces in a certain way. It will definitely be visible, therefore it may be seen as a kind of statement. Such strategy may be suitable for exhibitions of archival materials and group exhibitions. In such cases the project aesthetics may reflect certain assumptions of a curator, communicate thoughts, emotions or present the nature of a given era. Such strategy is bothersome for some viewers and irritates them. For others, on the other hand, it proves very satisfactory. Out of the two options, the latter is definitely the more risky path as it requires feedback from the audience more blatantly. Sometimes their reactions can be impetuous.

PG: What can be problematic for exhibition designers nowadays?

PTN: I wonder what the future holds for these professionals. We need to realize that there is an increasing number of artworks created with the use of new media and this is why it has to be carefully analyzed whether exhibition designers should be in the swim of all the technology involved or they should leave it to the professionals working with the technical aspects of projectors, audio equipment, etc.

When it comes to art exhibitions, in my opinion designers should be ready to take up more mundane tasks in the future, mostly related to economizing on resources. This is not only about the budget, but also about building materials and effective use of working time. We should work so that excess no matter is generated that will not be utilized in any way later on. I think that in the future all exhibition-related activities will be more modest. This reflection stems from the reality which galleries face right now, because they rely on public funding and may be financially affected by the pandemic. Anyway, it was not due to COVID-19 that all the exhibition business got interested in Eco-saving. This topic was touched upon earlier on during the discussion about the impact that the Anthropocene has on the environment.

The art of exhibition is not only about galleries, but it is a hugely important part of infotainment as well. In these new centres, resources for exhibitions, as opposed to the gallery reality, seem endless. Big studios and huge teams work on such projects and the problems they face are on a different scale. Design issues there are related, for example, to the stability of various solutions, space productivity and security. The designers really design user experience, from the moment they enter up until they interact with the actual exhibit. Here comes an interesting question for me – how to make a balanced design of an exhibition which engages the audience, but does not turn into a funfair at the same time? Can we pass on knowledge in a manner which will not create a blatant ‘wow effect’?

‘Visual SPA’ in the offices in the Blue Skyscraper located at Plac Bankowy in Warsaw, photo by Kacper Minicel

PG: Which of the exhibitions you designed was the biggest challenge if you think about technical issues or the nature of works by a specific artist?

PTN: One of the extraordinary projects was “Tamam Shud” exhibition of works by Alex Cecchetti, organized at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art. I cooperated on this project with the curators, Joanka Zielińska and David Maroto. The exhibition was a medium for this artist to develop the narration for his book in which he tried to solve a crime mystery. David was another person who worked on his own project related to this particular exhibition. As part of his doctoral thesis he was writing a novel on how the exhibition was created. The protagonists of his novel were members of the team working on the project, so real persons were involved in fictitious plot. When we worked on this project we materialized the ideas of Alex and created individual parts of the equipment according to his recommendations. All of this happened in the context of the plot we did not know at that time. The “Tamam Shud” exhibition was an artwork in its entirety. The artist even planned the menu and the meals could have been ordered and consumed within the exhibition space. The project team and guests enjoyed this festive dinner on the vernissage day while other members of the audience were passing us by.

PG: What is the exhibition design project you are most proud of?

PTN: I am proud of the exhibitions which I created with Piotr Matosek that were the own, original projects of the Matosek/Niezgoda project duo. For nearly a year we led an experimental art-space in the centre of Warsaw, at Nowogrodzka street. This was an amazing space, mostly because you could have used it any way you liked. The owner of the building planned to tear the place down and to carry out some major renovation. We called the place #Poligon and organized ten exhibition-like events which were extremely interesting for us. We worked with an exhibition and space as time-based art, we explored ephemeral phenomena in exhibition art as well as the oppression of exhibitions which makes the audience behave in a particular way at a gallery. At this location we also organized workshops on designing exhibitions. We organized all these simultaneously with several exhibitions at various institutions, some of which were located outside of Warsaw. Apparently, a lot of challenges generated a lot of energy within us. This surge of energy kept us going until a year later when we organized a three-day exhibition in the offices in the Blue Skyscraper located at Plac Bankowy in Warsaw. This “Visual SPA” allowed the visitors to enjoy an ‘artistic treatment’ while directly interacting with artists. This happened in September 2016. In November we were trembling with cold on a guard duty in the street near provisional generators, at the same time producing an event which encompassed four performance spaces as part of the first edition of the Abstract Thinking Festival. In Mazowiecka street there was a stand with newspapers, collages and the act of forgiveness as towards the followers of Maria Kozłowska, in Ordynacka street – aria from “Rinaldo” opera directed by Maciej Chorąży. Zuza Golińska and Nomadic State duo cooperated with us at that time. I would like to retain this level of creative energy forever.

PG: What are the skills that an exhibition designer needs to master? What is the education you need to receive to become a professional in this field?

PTN: I am a graduate of The Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. My major was really in line with the field I work in because I prepared my diploma project at the Exhibition Design Studio. This studio was, however, focused on designing stands for fairs and shops rather than on presenting works of art. What we were taught at the Academy were mainly fine arts and a bit of technical knowledge on construction materials and lighting. What the programme lacked was knowledge about the work of museums, e.g. the issues related to renovating works of art. Designers who work with archival works must be aware how to protect objects against harmful environmental factors. What is more, there is an increasing number of multimedia works. Therefore exhibition designers would find knowledge about relevant equipment and acoustics handy. If it were up to me, I would add another aspect, which is awareness of ecology. We should process and convert more, use less toxic materials. I can see that currently institutions follow such new, more cautious and ecological approach and I am very happy about it.

‘Visual SPA’ in the offices in the Blue Skyscraper located at Plac Bankowy in Warsaw, photo by Kacper Minicel

PG: Does the history of your studio influence your work?

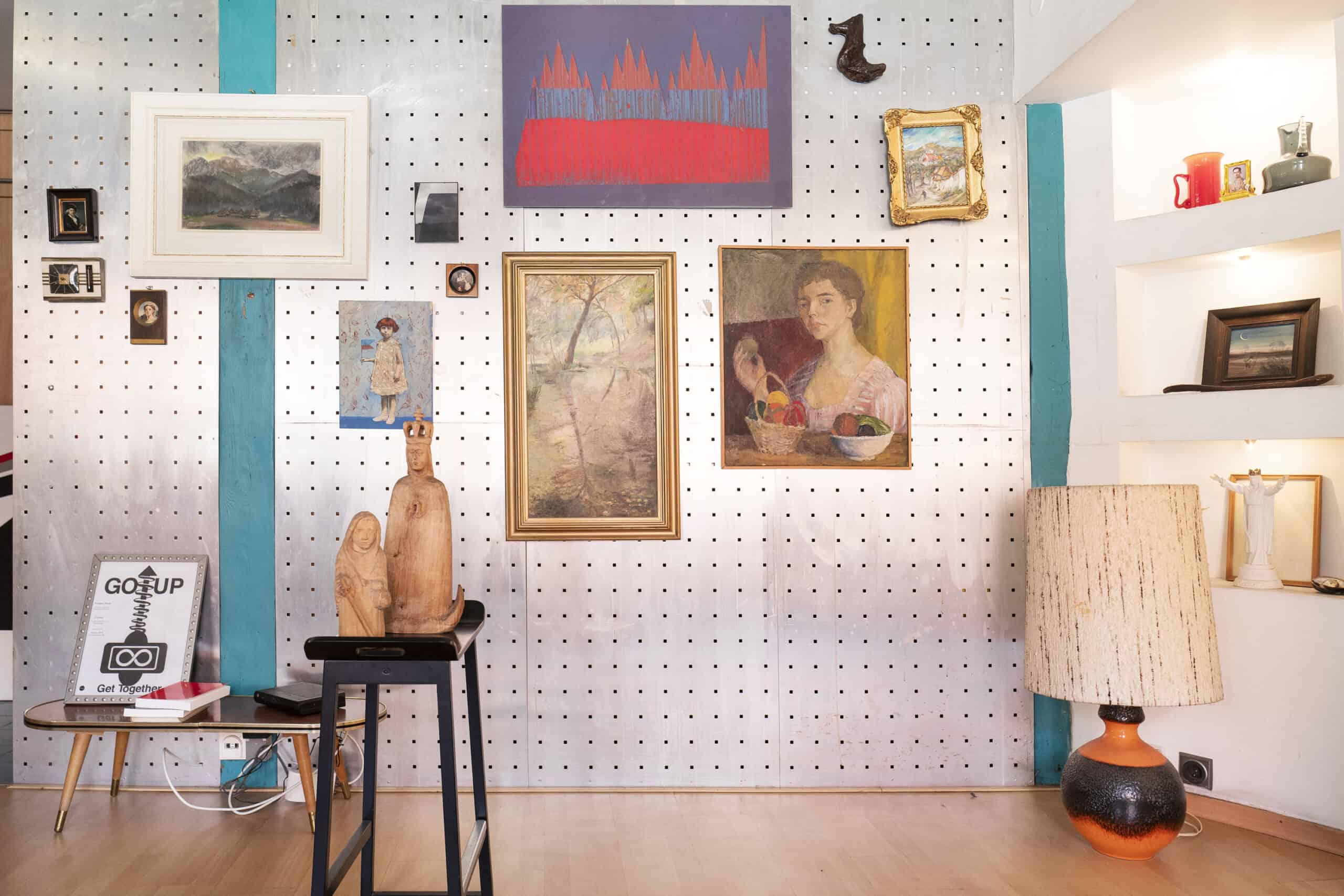

PTN: For sure it does! In this studio I could ask my grandmother for suggestions when it comes to painting and talk to my parents about architecture and design. I am sure this made it easier for me to begin my career. I have been working here since I was a student, i.e. since the year 2002. Just like other students, I wanted to be as active as possible “at a computer”, but our professors preferred traditional methods of work, such as creating models and drawing charts by hand. I am curious whether it still is like that. A room occupied by a student of interior design was like a factory of models, where you waded through pieces of cardboard and stumbled on glue containers. I had an opportunity to organize such workplace here. I am happy that there is a lot of space here to accommodate what I want. If I wish, I can organize myself a sewing table, because I recently got interested in sewing. I can also work with large formats, prototypes of stage design elements and anything I need to try out. There is even an exhibition space. Here I currently display works by my grandmother and several artists I know in person, but I am thinking about designing a specific form for this space and making a project around it. There are more things I plan to present and I would like to do it so that the display strongly interconnects with the interior. I think that in this way I will continue the process of transformation which is so characteristic for this place. I also plan to somehow make it available to the public.

PG: Are there any additional artistic activities organized in your studio as one of the historic art studios?

PTN: My studio only just became a historic art studio and all the administrative formalities are not over yet. Despite that, I managed to host the Teraz Poliż theatre collective in here. My studio was one of the highlights of an Old Town walk with dramatic productions by female artists. One of the works was read out and performed here and the audience from outside was invited. Soon, thanks to the cooperation with the Warsaw Historic Art Studios Team, I will invite here students from the New Media Department of The Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Their task will be documenting the interiors and objects collected here. I am looking forward to cooperating with them.

PG: To conclude our conversation, let’s go back to the beginnings of this studio. Can you tell us something more about the work of your grandmother who was the first person using this studio?

PTN: My grandmother, Barbara Pisarczyk-Niezgoda, studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. She graduated in 1955. When she was still a student, she took part in ethnographic exploration field trips organized by Professor Roman Reinfuss. She prepared drawings of certain elements of traditional wood architecture. She was also one of the creators of the visual setting of the 5th International Youth and Students Festival. I even have a few beautiful pictures from that time. At the later stages of her career she created illustrations and designs for books for Czytelnik publishing house. In the late 1960s and early 1970s she cooperated with Cepelia for whom she created objects decorated with painted motives. Some of these works stood the test of time and can be seen in my studio.

The main area of my grandmother’s activity was always painting. She specialized, for example, in landscape painting. She loved plein-air workshops, she eagerly participated in them and prepared materials for her work series she painted later on in the studio. She left me some specialist equipment, which is a fold-out easel to be used while painting outside (it folds just like a suitcase), as well as wooden cases for paints and brushes with straps attached, so that it was easy to carry them on the shoulder.

Her second speciality were portraits. I see the ones in miniature sizes as truly unique. There are also some of her miniatures with copies of old master paintings left until the present day, as well as several contemporary portraits. When they are presented together, they just look fantastic. When you look at them all, you can see the continuity of the portrait idea, which was a ‘selfie’ of the pre-digital era.

Ula Sieckle, Wolne gesty, U-Jazdowski, February 2018, photo: matosekniezgoda

Paulina Tyro-Niezgoda. Graduated from The Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw where she obtained her degree at the Interior Design Department. She obtained her MA diploma with distinction at the Exhibition Design Studio of Professor Henryka Noskiewicz-Gałązka. She received the Ministry of Culture Scholarship. Since 2009 she has been cooperating with Polish and international art institutions. In 2015 within the Wrocław European Capital of Culture project she designed an exhibition that was one of the official events of the 56th Venice Biennale. She created a creative duo with Piotr Matosek in 2015 and they focus on designing exhibitions. The Matosek/Niezgoda duo created exhibition spaces in the National Museum in Warsaw (including the permanent exhibition, namely the Gallery of Polish Design), Zachęta National Gallery, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, BWA in Tarnów and many other institutions. Together with Piotr Matosek she managed an independent art-space in Warsaw called Poligon. At that time 10 art events were organized at Poligon, namely exhibitions, performances and lectures, as well as a series of workshops on exhibition design entitled “Ex-around”.

The project is co-financed by the Capital City of Warsaw

Art Studio of Paulina Tyro-Niezgoda, photo by Michał Korta

“PRACOWNIA TO DLA MNIE TAKI FUTERAŁ. MAM TU ODGNIECIONY SWÓJ KSZTAŁT”.

Z WIZYTĄ W WARSZAWSKIEJ HISTORYCZNEJ PRACOWNI ARTYSTYCZNEJ UŻYTKOWANEJ PRZEZ PAULINĘ TYRO-NIEZGODĘ.

Kilka tygodni temu miałam przyjemność odwiedzić projektantkę wystaw Paulinę Tyro-Niezgodę w użytkowanej przez nią pracowni usytuowanej w wyjątkowo malowniczym miejscu, tuż przy Rynku Nowego Miasta w Warszawie. Artystka zdradziła na czym polega praca projektanta wystaw, jaką rolę odgrywa w jej pracy twórczej zajmowana pracownia oraz przybliża historię tej niezwykłej przestrzeni, którą niegdyś użytkowała jej babcia Barbara Pisarczyk-Niezgoda.

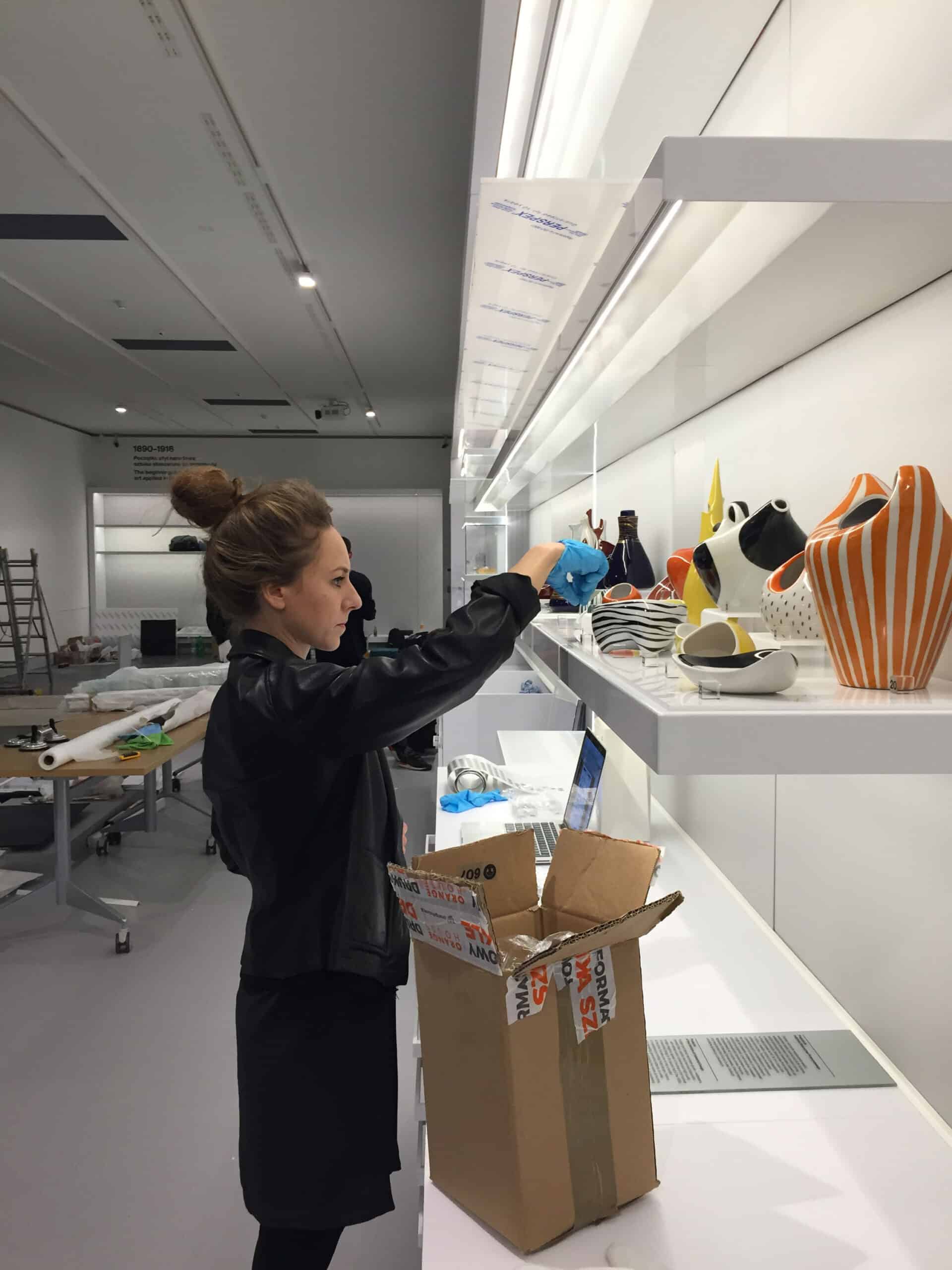

National Museum of Warsaw, Gallery of Polish Design, permanent exhibition, photo by matosekniezgoda

Patrycja Głusiec: Kwestia przestrzeni odgrywa ogromną rolę w twojej działalności. Zastanawiam się jaką rolę pełni dla Ciebie pracownia?

Paulina Tyro-Niezgoda: Kiedyś podobne pytanie zadał nam, studentom, prof. Andrzej Dłużniewski. Prowadził wtedy zajęcia na warszawskiej ASP. Odpowiedziałam, że pracownia, to dla mnie taki futerał. Mam tu odgnieciony swój kształt. Wciąż widzę to podobnie.

PG: Doprecyzujmy. Pracownia, którą obecnie zajmujesz znajduje się na terenie warszawskiej Starówki – miejsca niezwykle turystycznego. Jednak Twoja obecność, pracownia i międzypokoleniowe powiązanie z tym miejscem pokazuje, że jest to jak najbardziej rejon zwrócony także ku mieszkańcom. Czy mogłabyś opowiedzieć nam historię tej warszawskiej pracowni historycznej?

PTN: Historia pracowni zaczęła się w 1982 roku – wtedy mojej babci Barbarze, malarce, przydzielono przestrzeń, w której mogła zorganizować swoje miejsce pracy. To były ciekawe czasy – inne… Czy możemy sobie teraz wyobrazić, że w budynkach komunalnych masowo powstają pracownie? Starówka była jednym z miejsc na mapie Warszawy, gdzie takich przestrzeni było sporo – lokowano je głównie na strychach kamienic. „Nasza” pracownia, w momencie oddania do użytkowania, była w stanie surowym, bez instalacji elektrycznej, wody i ogrzewania, a wewnątrz latały gołębie. Doprowadzenie jej do użyteczności było koniecznością, a w związku z tym, wnętrze zmieniało się w zasadzie w trybie ciągłym przez kolejnych 30 lat. Urządzanie pracowni było festiwalem zaradności i pomysłowości, jak wiele działań w PRL. Dodatkowo, w pracowni zaczęli realizować swoje architektoniczne i designerskie pasje także moi rodzice. Myślę, że to zadecydowało o długim procesie przeobrażeń wnętrza pracowni – przestrzeń była plastyczna. Zmieniały się funkcje poszczególnych pomieszczeń, ich kształt, przybywały lub znikały charakterystyczne elementy. W tych zmianach widzę mocną tendencję do podnoszenia komfortu użytkowania – pracownia była miejscem, w którym spędzało się mnóstwo czasu, nie dziwi więc fakt, że powoli stawała się rodzajem drugiego domu. Żałuję tylko niektórych modernizacji. Kiedyś były tu takie wspaniałe, długie, żeberkowe kaloryfery z fabryki. Nie ma ich już, bo zarządca budynku nakazał modernizację i ujednolicenie sieci grzewczej. Powiedzmy jednak, że to czynnik zewnętrzny. Natomiast pracownię foto, która kiedyś tu była, zlikwidowaliśmy sami. Chyba wydawało się wtedy, że fotografia analogowa już nigdy nie wróci.

PG: Jak to się stało że twoja babcia zaczęła użytkować tę pracownię?

PTN: Możliwość użytkowania pracowni miała źródło w ówczesnej polityce miasta. Pracownie artystyczne pojawiały się w różnych miejscach Warszawy, wiele na Starym Mieście. Część artystów otrzymywała lokale użytkowe na parterach, z możliwością dojazdu samochodem. Inni, lokale-wyzwania, które należało własnymi nakładami „wznieść”. Było to rok przed moim urodzeniem. Barbara i Paweł, a więc moja babcia i ojciec, wybrali właśnie ten strych z pięciu innych możliwych lokalizacji. Miejsce wydawało się najciekawsze, mimo tego, że trzeba było je ogrzać i doświetlić. Po 37 latach, historia pracowni weszła w nowy okres. W 2019 roku Barbara odeszła. Po jej śmierci zaczął się proces przeobrażenia i starania o włączenie pracowni w grono pracowni historycznych.

PG: Przeistaczanie miejsca to niezwykle intrygująca kwestia, którą zajęłaś się zawodowo, jeśli możemy tak powiedzieć. Kiedy zwiedzający pojawia się na wystawie najczęściej nie myśli o tym, kto zaprojektował jej przestrzeń. Pierwsze myśli kierują się najczęściej ku artyście, następnie pojawia się postać kuratora. Natomiast to właśnie projektant wystaw materializuje wizję zespołu pracującego nad wystawą oraz wpływa na to jak zostanie odebrana. Czy mogłabyś pokrótce opowiedzieć o procesie powstawania wystawy oraz roli jaką pełnisz?

PTN: Proces powstawania wystawy w instytucji sztuki bywa dość długi. To chyba jedna z jego cech charakterystycznych. Tutaj rzeczy nie dzieją się z dnia na dzień, jak w innych branżach. Tworząc wystawę, zespół potrzebuje czasu na różne uzgodnienia. W procesie tych uzgodnień projektant jest pośrednikiem między wizją kuratora lub artysty, a producentem.

Projektant opracowuje koncepcję organizacji przestrzeni i podsumowuje ją w formie technicznego dossier, na bazie którego można wyprodukować wystawę, czyli wycenić i zlecić realizację poszczególnych elementów. W tym dossier zawiera się plan przestrzeni, odzwierciedlający przebieg narracji kuratorskiej, a także ustawienie i zawieszenie prac. Ich aranżacja w przestrzeni powinna uwzględniać osie widokowe, które będą otwierać się przed zwiedzającymi, a także wprowadzenie buforowej pustki wokół dzieł, która umożliwi kontakt z każdym obiektem z osobna.

Elementem projektu wystawy jest także mała architektura, czyli ściany działowe, wprowadzające dodatkowe podziały przestrzeni oraz wybór kolorystyki tła i innych elementów, w tym detali takich jak profile ram. Projektant proponuje także formę mebli ekspozycyjnych, czyli wszelkiego rodzaju półek, gablot, stołów, kloszy i siedzisk. Dossier projektu zawiera wykonawcze rysunki techniczne wszystkich elementów.

Dodatkowo, jeśli nie ma konkretnych wskazań od artystów, projektant, w porozumieniu z kuratorem, decydują o tym, które z prac wideo widz zobaczy w formie projekcji, a które na innych nośnikach. Po stronie projektanta (i kuratora), jest decyzja o tym, czy w salach będzie słyszany dźwięk, czy też ścieżki dźwiękowe prac wideo będą dostępne na słuchawkach. Czy widz będzie miał możliwość usiąść, czy raczej stać, kontemplując konkretne dzieło?

Projektant podejmuje szereg małych i dużych decyzji, które ostatecznie wpływają na kształt przestrzeni wystawy i interakcję widza. Decyzje te staramy się podejmować z możliwie dużym wyprzedzeniem. Nie da się jednak ukryć, że proces projektowania wystawy – pomimo pozornej stateczności dużych instytucji sztuki – jest procesem bardzo dynamicznym. Zmiany w wyborze prac, zmiany zaleceń konserwatorskich czy zmiany wynikające z kwestii technicznych czy produkcyjnych, są częste. Ukoronowaniem zaś całego procesu jest święto montażu, czyli czas, w którym działania zespołu radykalnie się zagęszczają. Podczas montażu problemy i rozwiązania pojawiają się spontanicznie, a część decyzji musi być podjęta raz jeszcze. Obiekty przyjeżdżają najczęściej dopiero w trakcie montażu – wtedy widzimy je po raz pierwszy na żywo, wcześniej zazwyczaj na zdjęciach. Tworząc projekt posługujemy się zatem informacjami przedłożonymi przez artystów lub właścicieli prac – dostajemy od nich np. formaty prac. Niespodzianki w postaci różniących się rzeczywistych formatów obiektów, zdarzają się często. Podobnie, kiedy tworzymy konstelacje – obiekty zestawione ze sobą w rzeczywistości czasem nie wyglądają ze sobą tak dobrze, jak wydawało się to wcześniej na papierze. Montaż jest tym momentem, kiedy projekt przybiera swój ostateczny kształt.

PG: W jaki sposób działania projektanta wystawy łączą się z pracą kuratora, konserwatora oraz producenta? Jak ważne jest współdziałanie?

PTN: Ostateczna forma wystawy jest zawsze wynikiem negocjacji projektanta z kuratorem, konserwatorem, działem technicznym itd. Oczywiście, nie każda wystawa ma projektanta. Czasem rolę tę pełni kurator, czasem projektantem jest sam artysta. Przypuszczam, że niszę tego zawodu wytworzył ogólny trend tworzenia specjalizacji.

Beyond the Desk International Office Art Biennale; Not Fair 2017; curators: Ewa Borysiewicz & Romuald Demidenko; artists: Jan Domicz, Richard Grandmorin, Gizela Mickiewicz, Polen Performance, Małgorzata Szymankiewicz, photo: Bartosz Górka

PG: Czy mogłabyś opowiedzieć o strategiach projektowania wystaw?

PTN: Zainteresowanych strategiami wystawiania odsyłam do „Display”, antologii pod redakcją Marii Haussakowskiej i Ewy Tatar. Jeśli zaś chodzi o projekt – można obrać strategię przezroczystości projektu, albo – nazwijmy to – wyrazistości.

Przezroczysty projekt to taki, który nie będzie widoczny – wystawa będzie po prostu dobrze zorganizowana przestrzennie i funkcjonalnie, nie będziemy się nad tym zastanawiać.

Projekt wyrazisty może natomiast w pewien sposób interferować z eksponowanym materiałem. Będzie widoczny, a przez to może stanowić pewnego typu wypowiedź. Taką strategię można obrać np. projektując wystawy archiwalne i zbiorowe – w tym przypadku, estetyka projektu może oddawać jakieś założenia kuratorskie, wyrażać myśl, emocję czy charakter epoki. Dla części odbiorców taka strategia jest trudna w odbiorze, drażniąca, dla części satysfakcjonująca. Na pewno jest to strategia bardziej ryzykowna, ponieważ bardziej domaga się od widzów informacji zwrotnej. Reakcje potrafią być czasem żywiołowe.

PG: Co może dzisiaj sprawiać problem projektantom wystaw?

PTN: Zastanawiam się, jaka przyszłość czeka ten zawód. Biorąc pod uwagę wzrastającą ilość prac z wykorzystaniem nowych mediów, powinniśmy zastanowić się, czy projektant powinien trzymać rękę na pulsie technologicznych kwestii, czy raczej oddać to profesjonalistom, skoncentrowanym stricte na aspektach technicznych projektorów, sprzętu audio itp.

Jeśli myślimy o wystawach sztuki, sądzę, że projektanci wystaw powinni w przyszłości przygotować się na bardziej przyziemne działania, dążące do ekonomicznego wykorzystania zasobów. Chodzi nie tylko o budżet, ale też materiały budowlane i ekonomiczne wykorzystanie czasu pracy. Powinniśmy działać tak, by nie generować nadmiarowej materii, która nie znajdzie późniejszego zastosowania. Myślę, że działania ekspozycyjne będą w przyszłości bardziej skromne. To oczywiście refleksja pochodząca ze świata galeryjnego, który uzależniony jest od środków publicznych i może doświadczyć finansowych konsekwencji pandemii. Tym niemniej, to nie Covid wprowadził w świat wystaw wątek eko-oszczędności. Pojawił się on już wcześniej, przy okazji dyskusji o ekologicznych konsekwencjach antropocenu.

Poza galeriami, wystawiennictwo to także ogromna gałąź infotainment-u. W tych nowo tworzonych centrach, środki przeznaczane na wystawy – w porównaniu ze światem sztuki – wydają się niewyczerpane. Przy tych projektach pracują duże pracownie i ogromne zespoły, a problemy mają inną skalę. Kwestie projektowe dotyczą np. trwałości różnych rozwiązań, wydolności przestrzeni, bezpieczeństwa. Projektanci rzeczywiście projektują tu doświadczenia widza, od wejścia, po kontakt z eksponatem. I tu pojawia się moim zdaniem ciekawe zagadnienie: jak wyważyć projekt wystawy, by angażowała widzów, ale nie zmieniała się w rodzaj lunaparku? Czy możemy przekazywać wiedzę w sposób, który nie będzie nachalnie wywoływał efektu „wow”…?

PG: Która z zaprojektowanych przez Ciebie wystaw była największym wyzwaniem, być może właśnie ze względu na problemy techniczne lub może ze względu na twórczość danego artysty?

PTN: Wyjątkowym projektem była współpraca przy wystawie „Tamam Shud” Alexa Cechettiego w Zamku Ujazdowskim w Warszawie, której kuratorami byli Joanka Zielińska i David Maroto. Dla artysty, wystawa była medium budującym narrację książki, w której starał się rozwiązać kryminalną zagadkę. Równolegle do projektu Alexa, swój projekt, będący częścią pracy doktorskiej, rozwijał David, pisząc powieść o powstawaniu tej wystawy. W powieści Davida znalazł się zespół pracujący nad wystawą, rzeczywiste postaci, choć wplecione w fikcyjną narrację. Współpracując przy tym projekcie, materializowaliśmy koncepcje artysty, tworząc elementy wyposażenia wystawy wg wskazań Alexa. Wszystko to w kontekście fabuły, której treści jeszcze nie znaliśmy. Wystawa „Tamam Shud” była dziełem totalnym artysta zaplanował nawet menu dań, które można było zamówić i zjeść uroczyście w przestrzeni wystawy. Nasz projektowy duet oraz goście, zjedliśmy tę wyjątkową kolację w dniu wernisażu, mijani przez uczestników otwarcia.

‘Visual SPA’ in the offices in the Blue Skyscraper located at Plac Bankowy in Warsaw, photo by matosekniezgoda

PG: Z którego projektu wystawy jesteś najbardziej dumna?

PTN: Jestem dumna z wystaw, jakie – wspólnie z Piotrem Matoskiem, z którym tworzę projektowy duet Matosek/Niezgoda – przygotowaliśmy w ramach naszej autorskiej działalności. Przez niemal rok prowadziliśmy eksperymentalny art-space w centrum Warszawy, przy ul. Nowogrodzkiej. To była wspaniała przestrzeń, przede wszystkim dlatego, że można było zrobić z nią dosłownie wszystko. Właściciel budynku planował wkrótce wyburzenie wnętrz i generalny remont. Miejsce nazwaliśmy #Poligon i przygotowaliśmy tam 10 wydarzeń w ekspozycyjnych formułach, które były dla nas interesujące: pracowaliśmy z medium wystawy i przestrzenią jako time-base art, eksplorowaliśmy wątki wystawienniczych efemerów i ekspozycyjnej opresji, nakazującej widzom konkretne zachowania w galerii. W tym samym miejscu prowadziliśmy także warsztaty na temat projektowania ekspozycji. Wszystko to działo się równolegle z kilkoma projektami wystaw w różnych instytucjach, także poza Warszawą. Najwyraźniej duża ilość wyzwań generuje także sporą dawkę energii. Na fali tej mocy surfowaliśmy jeszcze rok później, organizując trzydniową wystawę w biurach Błękitnego Wieżowca na Placu Bankowym w Warszawie, gdzie w ramach „Wizualnego Spa” można było zażyć artystycznego zabiegu prowadzonego w bezpośrednim kontakcie z artystą. To był wrzesień 2016, a w listopadzie – trzęsąc się z zimna podczas ulicznej warty nad partyzancko rozstawionymi agregatami, produkowaliśmy wydarzenie składające się z czterech przestrzeni performatywnych w ramach pierwszej edycji FMA (Festiwal Myśli Abstrakcyjnej). Na Mazowieckiej był kiosk z prasą, kolażami i przebaczeniem Marii Kozłowskiej, na Ordynackiej – aria z opery „Rinaldo” reżyserowana przez Macieja Chorążego. Działali z nami też Zuza Golińska i duet Nomadic State. Chciałabym, żeby ten poziom energii utrzymał się na zawsze.

PG: Jakie umiejętności powinien posiadać projektant wystaw? Czy mogłabyś wskazać ścieżkę edukacji, która pozwala na doskonalenie się w tej dziedzinie?

PTN: Ja jestem absolwentką Warszawskiej ASP. Moje wykształcenie jest wybitnie kierunkowe, ponieważ dyplom robiłam właśnie w pracowni wystawiennictwa. Pracownia ta nie była jednak skoncentrowana na wystawianiu sztuki – tu chodziło także o stoiska targowe i sklepy. Akademia kształciła więc ogólnie w zakresie zagadnień plastycznych, dodając nieco wiedzy technicznej, na temat materiałów konstrukcyjnych i oświetlenia. Zabrakło tu problematyki stricte muzealnej, czyli np. zagadnień konserwatorskich. Projektanci pracujący z archiwami powinni być świadomi tego jak zapewnić obiektom ochronę przed szkodliwymi czynnikami środowiskowymi. Po drugie, coraz więcej prac artystycznych wykorzystuje multimedia. Dlatego dla projektantów ważna będzie także wiedza na temat możliwości sprzętowych i akustyki. Wprowadziłabym jeszcze dodatkowy aspekt, czyli świadomość ekologiczną. Więcej przetwarzajmy, używajmy mniej toksycznych materiałów. Widzę, że takie nowe, bardziej powściągliwe i pro-ekologiczne podejście pojawia się teraz w instytucjach i bardzo się z tego cieszę.

PG: Czy historia pracowni ma wpływ na Twoją działalność?

PTN: Na pewno! Tu w pracowni mogłam poradzić się babci w sprawach malarskich i rodziców w kwestiach architektury i wzornictwa. Na pewno ułatwiło mi to start. Pracuję tu od czasu studiów, czyli 2002 roku. Podobnie jak inni studenci – chciałam wtedy jak najwięcej działać „w komputerze”, ale nasi wykładowcy woleli tradycyjne metody pracy, takie jak tworzenie makiet, odręczne wykreślanie plansz itd. Ciekawe, czy to dalej tak wygląda? Pokój studenta Architektury Wnętrz to była taka makieciarnia, gdzie brodziło się po kostki w skrawkach tektury i potykało o puszki kleju. Ja miałam możliwość tę roboczą przestrzeń mieć tu w pracowni. Cieszę się, że jest tu miejsce na wszystko. Jeśli chcę, mogę zorganizować sobie miejsce do szycia, co ostatnio mnie interesuje. Albo zająć się dużymi formatami, prototypami elementów scenografii, czymkolwiek, co potrzebuję zbadać. Jest tu nawet przestrzeń ekspozycyjna. Wiszą tu teraz prace babci i kilku znajomych artystów, ale myślę o nadaniu temu przemyślanej formuły i rozwinięciu w konkretny projekt. Jest więcej rzeczy, które planuję pokazać i chciałabym zrobić to w taki sposób, aby display wszedł w mocną relację z wnętrzem. Myślę, że w ten sposób przedłużę charakterystyczny dla tego miejsca proces przemian. Zakładam też, że w jakiś sposób udostępnię go publiczności.

National Museum of Warsaw, Gallery of Polish Design, permanent exhibition, photo by matosekniezgoda

PG: Czy w ramach pracowni historycznych odbywają się u was dodatkowe działania artystyczne?

PTN: Pracownia dopiero zaczyna swoją działalność w roli pracowni historycznej, z urzędowego punktu widzenia formalności nie są jeszcze dopełnione. Zdążyłam jednak ugościć tu kolektyw teatralny Teraz Poliż. Pracownia ta była jednym z przystanków staromiejskiego spaceru z dramaturgią kobiecą. Odbyło się tu performatywne czytanie jednego z tekstów przy udziale publiczności. Niebawem, dzięki współpracy z Zespołem do spr Warszawskich Historycznych Pracowni Artystycznych, pojawią się tu także studenci z Wydziału Nowych Mediów warszawskiego ASP, z zadaniem wykonania autorskiej dokumentacji wnętrza i zgromadzonych tu obiektów. Cieszę się na tę współpracę.

PG: Na koniec naszej rozmowy powróćmy do początków pracowni. Czy możesz więcej opowiedzieć o twórczości swojej babci i pierwszej użytkowniczki pracowni?

PTN: Moja babcia, Barbara Pisarczyk-Niezgoda, studiowała malarstwo na Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie. Dyplom obroniła w 1955 roku. Jeszcze jako studentka, uczestniczyła w etnograficznych badaniach terenowych prof. Romana Reinfussa, przygotowując dokumentację rysunkową elementów tradycyjnej architektury drewnianej. Znalazła się także w zespole twórców oprawy plastycznej V Światowego Festiwalu Młodzieży i Studentów. Mam z tego okresu kilka pięknych pamiątkowych zdjęć. W swojej późniejszej zawodowej karierze zajmowała się tworzeniem ilustracji i projektami książek dla wydawnictwa Czytelnik, a na przełomie lat ‘60 i ‘70 współpracowała z Cepelią, na zlecenie Centrali tworząc przedmioty zdobione malarskimi motywami. Kilka takich prac zachowało się i można zobaczyć je w pracowni.

Głównym obszarem jej twórczości było jednak zawsze malarstwo. Specjalizowała się między innymi w pejzażach. Uwielbiała plenery, jeździła na nie dużo i chętnie, przygotowując materiał do późniejszych cykli, które powstawały w pracowni. Po Barbarze został mi specjalistyczny sprzęt w postaci plenerowej rozkładanej sztalugi (składająca się jak walizka) i drewnianych kaset na pędzle i farby, wyposażonych w paski, dzięki którym można było nosić je na ramieniu.

Drugą specjalnością Barbary były portrety. Dla mnie, wyjątkowe są te w miniaturowych formatach. Zachowało się kilka miniatur z kopiami obrazów starych mistrzów i kilka portretów współczesnych. Fantastycznie wyglądają zestawione razem. Widać wtedy ciągłość idei portretu w miniaturze – swoistego „selfie” epoki przedcyfrowej.

Art Studio of Paulina Tyro-Niezgoda, photo by Michał Korta

Paulina Tyro-Niezgoda: Absolwentka wydziału Architektury Wnętrz Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie. Dyplom z wyróżnieniem obroniła w pracowni projektowania wystaw prof. Henryki Noskiewicz-Gałązki. Stypendystka Ministerstwa Kultury. Od 2009 roku współpracuje z polskimi i zagranicznymi instytucjami sztuki. W 2015 roku w ramach Wrocławia Europejskiej Stolicy Kultury, zaprojektowała wystawę będącą jednym z oficjalnych wydarzeń towarzyszących 56. Biennale w Wenecji. Od 2015 roku wraz z Piotrem Matoskiem współtworzy duet projektowy, specjalizujący się w aranżacji wystaw. Przestrzenie ekspozycyjne projektu studio Matosek/Niezgoda oglądać można w Muzeum Narodowym w Warszawie (tam również wystawę stałą – Galerię Polskiego Wzornictwa), Zachęcie – Narodowej Galerii Sztuki, U-Jazdowskim, Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, BWA w Tarnowie i innych. Wraz z Piotrem Matoskiem, współprowadziła w Warszawie niezależny art-space, Poligon. W ramach swojej działalności, Poligon zorganizował 10 wydarzeń artystycznych – wystaw, performance’ów i wykładów, a także cykl warsztatów dotyczących projektowania wystaw „Ex-around”.

Zdjęcia z pracowni: Michał Korta

Korta jest niezależnym fotografem portretowym i wykładowcą fotografii w Polsce i Szwajcarii. Najnowsze projekty obejmują: „Byłe republiki rosyjskie”, „Kazachski zsiadł z konia”, „Żołnierze izraelskie”, „Balkan Playground”, „The Shadow Line” i „Painter’s Notebook”.