Some places enrapture us with their magnificence at the very moment we come inside. A thin wooden skirting board at the threshold may reveal itself as a borderline between two completely different worlds. The apartment of Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczyk is teeming with unique objects. There are dried plants, butterflies affixed to extremely thin needles, old paintings and peculiar drawings everywhere the visitor looks. This is probably how one would imagine the room inhabited the protagonist of Susan Sontag’s novel “The Volcano Lover”. Unsurprisingly, there are uncommon stories in both of these fascinating rooms…

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, photo: Michał Korta

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, exhibition view, 2018, Henryk Gallery, Kraków, photo: Edyta Dufaj

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, “Jarden Brun” exhibition, Kadenówka mansion, Rabka Zdrój

Marta Kudelska: There are so many intriguing objects in your studio. To me, it looks a little bit like a cabinet of curiosities. Is this unusual kind of aesthetics a source of inspiration for you?

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczyk: I am an avid enthusiast of Renaissance and late Renaissance art. The first cabinets of curiosities were established in this period and the idea behind them was getting to know more about the world and becoming surrounded with the objects one can find on our planet. I am also a collector to some extent and objects serve as an impulse for me to create new projects. It is also extremely important for me that they give me inspiration both in terms of form of my works and their content.

MK: Why do you collect all these objects?

WIS: The fact that I am interested in collecting as such does not stem from any disorder, nor compulsion or obsession. What I decide to include in my collection very often founds itself there for its sheer beauty. Sometimes I simply like an object very much and its form particularly appeals to me. In other cases, I collect things which invoke certain associations in me or which are associated with stories, experiences and references. I prepared works about the theatre of memory or various memorization techniques some time ago. In that case the whole process revolved around objects rather than rooms which used to be “memory reservoirs” for the ancients. It is not so for me since I see objects, not rooms, as triggers for memories.

MK: Are you sentimental about the objects you collect? Maybe you prefer the ones, which stir emotions in you or invoke some specific feelings? You certainly own artefacts which origin remains a bit mysterious for you. What is the decisive factor in the case of such objects – the aesthetic aspects or potential story which may reveal itself out of the initial mystery?

WIS: For me the object itself is what matters most. If we think about it as a carrier of memories, our perception of it immediately changes. It does not even matter that we are not familiar with the story behind the thing we are holding in our hands. I believe to some extent in such magic and metaphysics which allow us to recognize what is really special at the very moment we see it in front of us.

Wojciech Ireneusz sobczak, work from the Laboratory series, 2017, combine technique

Wojciech Ireneusz sobczak, work from the Laboratory series, 2017, combine technique

MK: It is as if we were talking about conjuring up ghosts.

WIS: I would agree that there is a certain resemblance. I think that very often an object is important to us but we are not really sure why. It may, of course, symbolize something, but apart from that this very object may make us feel that it has been through a lot before it found itself at the place it currently is. We simply feel that the story behind was good, bad or even tragic. I have a few such objects in my collection as well.

MK: Among all these objects, could you pick any favourites? Can you name the ones which are particularly valuable to you?

WIS: I do not think I have any definite favourites. I like every object in my collection in a unique way, I have different attitudes towards each of them. It is a bit as if you asked me whom of my friends I like most. It is impossible to answer that. Each one is unique, evokes different emotions and associations.

MK: Do you remember the very first object you wanted to keep? The one that started your collection?

WIS: The first objects I liked were connected to nature. These were artefacts from the woods, gardens and rivers. They had absolutely no material value. I remember, for example, that as a child I protested when my parents wanted to burn a tree which was earlier cut down. I simply liked it so much that I did not want to lose it. My parents obeyed so I kept this tree in my room although it was more than a meter high. It was so picturesque with all the twisted branches.

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, Plants, “Jarden Brun” exhibition, Kadenówka mansion, Rabka Zdrój, photo: E. Dufaj

MK: Is nature important to you? It appears very often in your works, to be honest.

WIS: As a child I used to work in a garden with my parents. I always was an inquisitive boy, so I wanted them to explain literally everything to me. It turned out that I learned a lot about plants and gardens at that time.

MK: When did you make a decision to study at the Academy of Fine Arts?

WIS: I knew it straightaway. Maybe I was not instantly sure about studying at the Academy, but I was certain that I wanted my career to revolve around art or crafts. When I started attending school, I simultaneously started extra classes in visual arts and artistic printing.

MK: It turned out that you studied graphic arts at the Academy.

WIS: I really liked graphic arts when I took these additional classes. I still remember how we made linocuts. These classes really made an impact on my decision as for further studies, although as a high school student I wished to study an architecture-related field for some time. The possible reason was that my high school did not really encourage us to pursue our artistic passions and engage in creative activities.

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, Shrine, Affinities I exhibition, Leto Gallery, Warsaw, photo: B. Górka

MK: Did your education at the academy have a significant impact on you? Did it help you define the direction to follow as a mature artist? Can you name a person who inspired you at that time?

WIS: I certainly felt that the people I was surrounded with were very important. I really appreciated the companionship of my fellow students and I have to admit that my class consisted of particularly talented and strong individuals. Many of them were later employed by various universities and they still engage in artistic activities, so they did not give up on their passion. The study programme itself turned out to be totally different from my expectations. At that time I was very critical of the surrounding reality. I also did not have “the master”, which may be why I was inspired by old art.

MK: One sentence from the text which advertises your exhibition entitled “Affinities I” organized at LETO Gallery in Warsaw is particularly intriguing, namely: “Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczyk is an artist who is decidedly uncontemporary.” What do you think about it? What are “the present times” for you?

WIS: In my opinion „the present times” reveal themselves in every artistic activity we undertake. We cannot avoid it and I definitely do not strive to distance myself from contemporary touches. My approach to what I do is not to follow the fashions or mainstream trends. I try to make sure I do what I really want and am true to what I feel. I do not want to deceive anybody. The term “uncontemporary” which was used in the sentence you mentioned also refers to the methods I use. It is really important for me to master particular techniques and to possess manual dexterity. I think that I will never perform any activities which do not involve manual work.

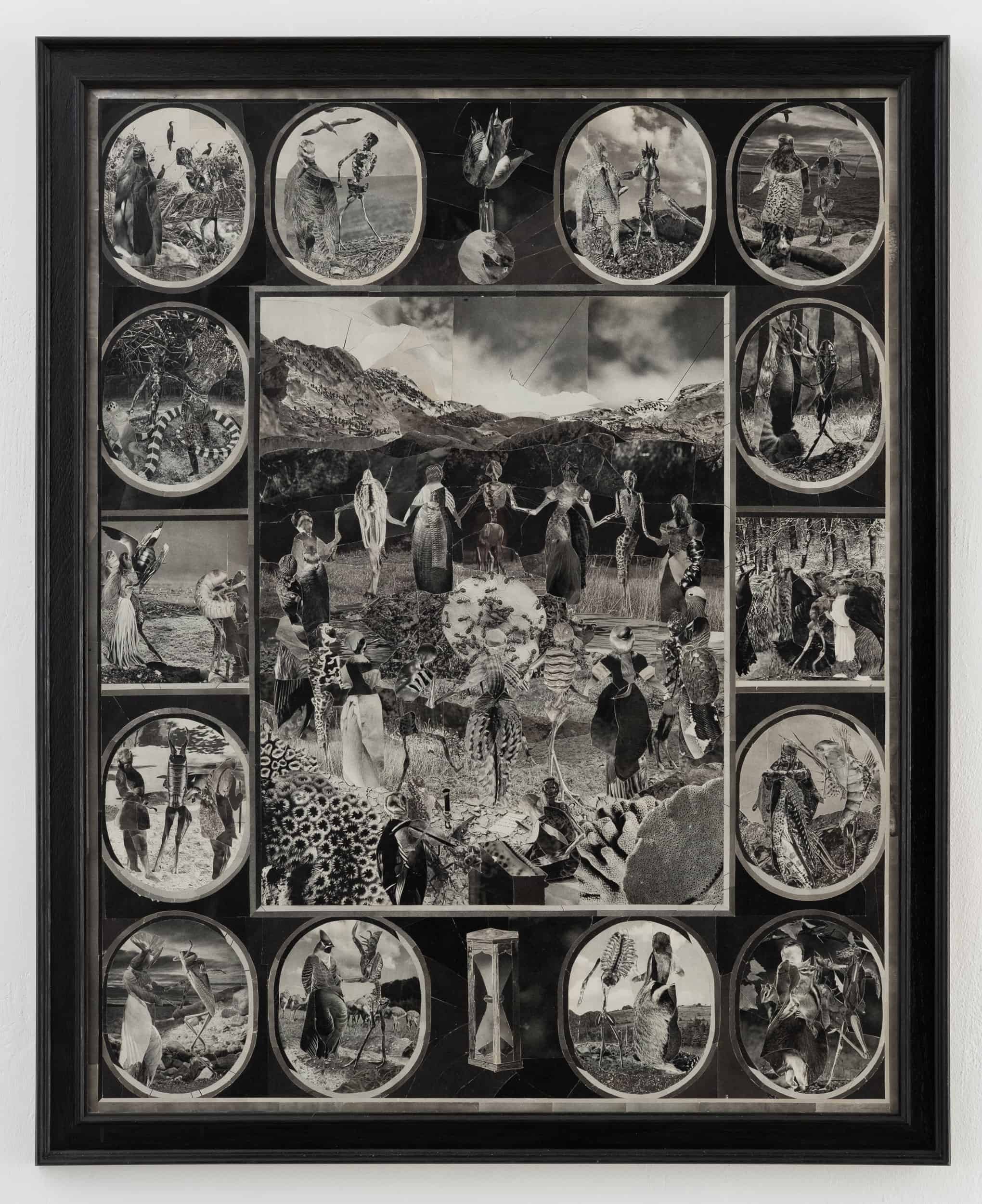

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, Danse Macabre, 2018, collage, photo: B. Górka

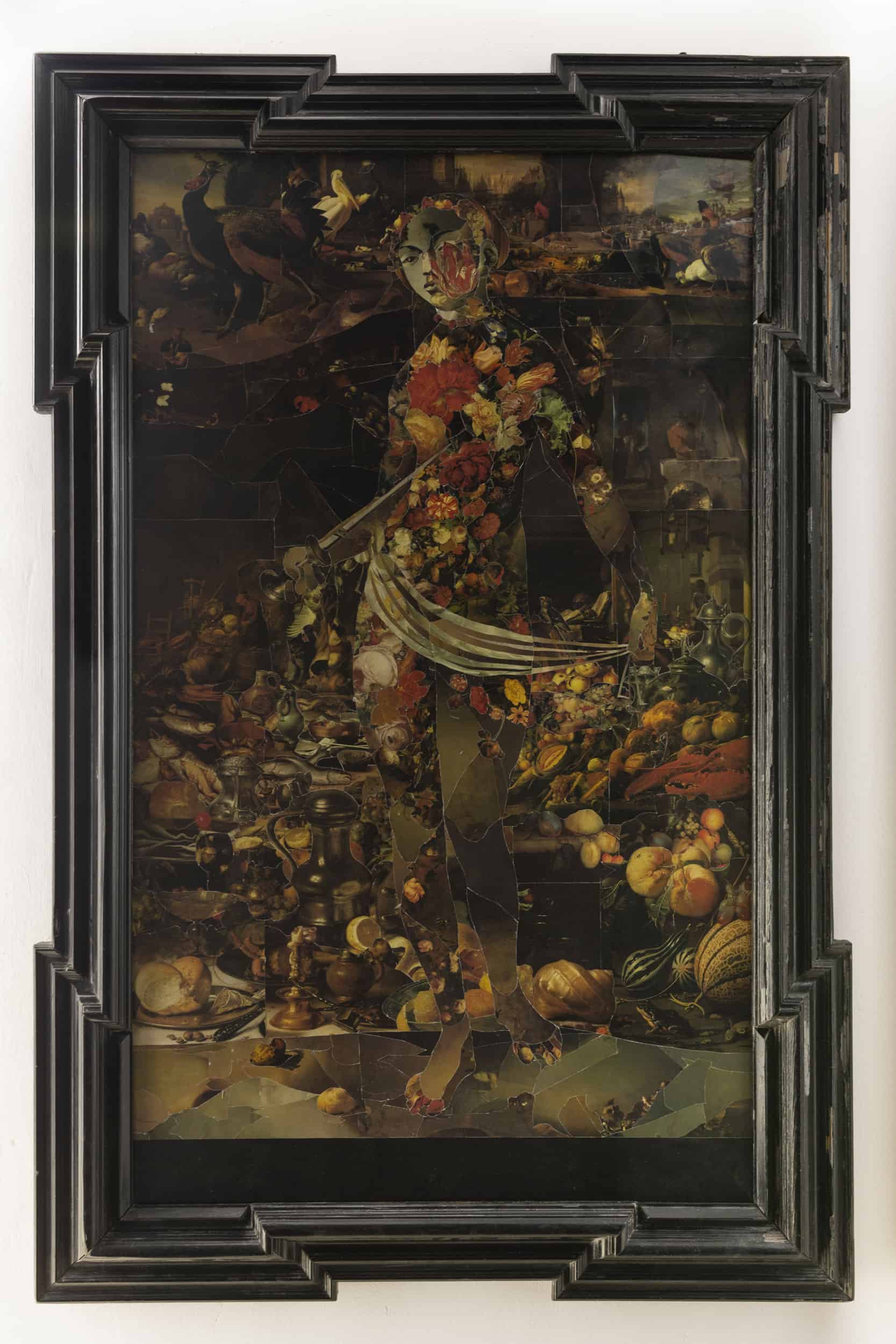

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, Lukrecja, 2018, collage, photo: B. Górka

MK: Is the moment when you can touch the matter important?

WIS: It is very important.

MK: We could say that your works are a story told with your hands. Where do your inspirations come from?

WIS: You mean where do I take my ideas from? I do not know the answer to this question myself. In my opinion, us artists do not have to completely understand how a given idea originated in our heads. Later on we have to think about the nature of an idea and what message it carries, but the very first concept can be like a bolt out of the blue and this is totally fine. We are then not able to make any detailed analysis of the primary concept, because it may be formed subconsciously and be a combination of multiple elements, the existence of which we do not fully realize. You asked me about my childhood experiences with nature and I admit it did not occur to me earlier, but now I realize that these experiences may help me answer the question of why I am doing what I am doing.

MK: I am glad you think of it this way. I would like us to talk about the past a little bit more. You often refer to old art in your works. I remember the exhibition at BWA gallery in Tarnów entitled “The Country’s Great Noblemen” (Wielcy sarmaci tego kraju / Wielkie sarmatki tego kraju) where you presented works inspired by coffin portraits which were a characteristic element of the Polish baroque. You also made reference to the “Dance macabre” painting, which used to be considered as painted by Franciszek Lekszycki and which can now be seen at Bernardine Church in Krakow. All these seem like very old inspirations, but this is not necessarily so. What else is important to you when it comes to the so-called “old art”?

WIS: I really appreciated the possibilities of seeing paintings by old masters, for example Piero della Francesca. I remember the deep impression after seeing his works. I think that my fascination with the “old masters” results from the fact that they possessed great skills, knowledge of technology and that their works lasted so long and did not become outdated at all. In fact, these are characteristics of good art. I never thought that an artists creates his works from scratch. He always refers to something. Contemporary art, which seems so innovative, also draws on the previous epochs. I try to make references to general ideas which have been present in people’s lives for a very long time and to key aspects in human life. I am, for example, interested in the question of what makes humans as they are, why do humans want to be considered “superior” to animals and what is the real difference between a human being and an animal. I want to research how the values of love, good, evil and truth function. All of them are big words which may seem a bit funny when said aloud. I also like the topics of “passing” and “memory”, which were discussed in so many contexts already. They are obviously always important but I think they should be presented in a way which would not deceive the audience. They should become a strategy for creating works of art. The crucial thing is to avoid clichés.

MK: At the recent “Weed Atlas” exhibition in Lublin you made an untypical reference to the history of the venue where the event was held. You presented a gigantic installation on eugenics, Polish-Jewish relations and other topics to comment on history of the tenement house in a non-anthropocentric way. The topic you presented can be considered “contemporary”.

WIS: The topic is indeed contemporary and very “popular”. I think it is vital for our generation, the generation of a “transition period”, as we had the chance to meet people who personally experienced the atrocities of war. These tragic experiences will just be an old history for next generations, but we live in these peculiar times and see that they were real. I think this is the reason that the topic is so extensively discussed. We simply so not know how to deal with this situation. My installation presented in Lublin related to the history of the venue, Labirynt Gallery at Grodzka street. The tenement house where the gallery is located was an apartment house where Jews lived before the war. The ceramic weeds hanging in the gallery symbolize Jews deportation from the city and number 700 is half of the number of Jews deported daily. This work was and is still extremely important for me because it made me realize how easy it is for us to quote numbers, but how little we understand them at the same time. The plants/weeds prepared for this exhibition made me “feel” how big the number I used really was.

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, Weed Atlas, exhibition view, Labitynt Gallery, Lublin, 2019, photo: B. Górka

MK: Why did you call it “Weed Atlas”? Is the title about people who can easily be uprooted, thrown away and rejected because they are not needed at all, just like ordinary weeds?

WIS: Indeed. When we grow plants in a garden we get rid of weeds. This, in fact, can be considered eugenics of sorts. In a specific context we get rid of plants which naturally are herbs, for example.

MK: Do you think then that it is important to know the context in order to understand art as such?

WIS: It obviously is important, but an artwork should also exist independently from an artist and be considered art by the audience. There are works, of course, which require the audience to familiarize themselves with the biography of their authors, but this is only a minor fraction of all the works created globally.

MK: This is, again, a very ‘uncontemporary’ and rather traditional attitude. Aren’t you afraid of what you just said?

WIS: When a vernissage of my works is organized I openly claim that I do not need to be present there. I have nothing to say because my works speak for themselves. If they really transfer the intended message, then I am successful. On the other hand, when they do not narrate, something surely went wrong. There are fields of art where commentary is indispensable and the presence of an artist is necessary as well. I think that I just followed a different direction, that is all. The ‘uncontemporary’ part is me not considering myself a necessary component of the works I create. I am more of a tool instead. I never make opening speeches at my vernissages because it is not me the audience should be looking at but my works.

MK: Last but not least, I would like to ask about your opinion on the Polish contemporary art. Do you think that artists are opportunistic and intentionally select popular topics? Maybe it is totally different in your view?

WIS: Art needs to present certain topics and reflect the spirit of the times. My works also revolve around contemporary topics but maybe a bit less directly. I do not think I am the right person to formulate such judgements. When it comes to reception itself, Polish art is certainly more recognizable and perceptible. The public gradually gets accustomed to it, learns how to interpret it, more and more people visit art exhibitions. This is kind of uplifting, but in comparison to other countries there is still a lot to ask for. Nevertheless, the situation has noticeably improved, so we should stay positive.

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, Love from Eight Fairy Tales, 2015, installation, Kraków, photo: E. Dufaj

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Katarzyna Nalezińska for her help in writing down this interview.

interviewed by Marta Kudelska

Wojciech Ireneusz sobczak, work from the Laboratory series, 2017, combine technique

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, Flowers from the Lukrecja series, 2018, ceramics

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, Lukrecja from the Laborathory series, 2018, sculpture

Wojciech Ireneusz Sobczak, Wurzel, Weed Atlas, exhibition view, Labitynt Gallery, Lublin, 2019, photo: B. Górka