Collecting works from the fields of ephemeral art, process art and performance art may be perceived as a futile effort. Nowadays, however, such attempts are essential because we live in an era in which many artists detach themselves from material artworks and focus on relational activities, post-artistic practices, theatre and dance. Bunkier Sztuki Gallery was following these trends and saw that they provided an opportunity for experimenting with the latest presentational techniques and new methods of preserving works of art which are “untypical” for a collection understood in the usual way.

Michalina Sablik: Most people do not realize that Bunkier Sztuki has its own collection of artworks, which is not presented at the gallery on a permanent basis owing to the limited space at the venue. What is the character of this collection and how was it started?

Anna Lebensztejn: Currently the collection includes 400 works plus deposits. It has really diversified over time. The gallery started collecting works as early as the 1960s, but works acquired between then and the 1980s were sold at an auction in 1993 by the director of the gallery at the time. The reason for the sale was the assumption that the conditions at Bunkier Sztuki were not appropriate for storing works of art. The collection has been rebuilt since the early 2000s. At that time the director, Jarosław Suchan, planned to extend the building and present the permanent collection on a new floor of the museum. Works collected were a “memory of the institution”. The gallery acquired and displayed works by many interesting emerging artists from Krakow, e.g. Wilhelm Sasnal and Marcin Maciejowski. At the time the gallery acquired mainly paintings, photographs, objects and video materials, selected because of their relation to the nature of planned exhibitions. The situation was quite similar after Maria Anna Potocka became the gallery director in 2010.

M.S.: In 2012 there was a shift in approach towards the collecting activities of Bunkier Sztuki. What was the reason for redefining the collection?

A.L.: We wanted to transform our collection into a city artworks collection, which would be different from museum collections owned by MOCAK [Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow] or the National Museum. Therefore, we focused on works which are not typically part of museum exhibitions, are mainly ephemeral or focused on a process. Eight years have passed since then and now such works have become a standard element of museum collections. When we started to follow this path the situation was much different and our approach was deeply experimental. We mainly purchased works which were commissioned, so the process of their creation itself became extremely important. Many of those works were site-specific and related closely to the character and identity of the gallery. These artworks function as first, production and subsequently, renditions, and therefore, instructions are their basic form.

M.S.: Collecting works from the field of ephemeral art and activities may be perceived as a futile effort. How does it work in practice?

A.L.: We collect various “untypical” works, such as performances, artistic actions, activities in public spaces. When it comes to restoration, storing and archiving, these works require a totally different approach than material works of art. First of all, we have to really think about what exactly it is that we are collecting. The crucial thing for us are authors’ certificates and instructions. Material aspects of these works are much less important than exhaustive instructions detailing performance or reconstruction. They need to thoroughly describe what is supposed to be happening with a given work. The first work of this kind in our collection was Pictures 2002 by Wojciech Gilewicz. This work is actually a constant painting process, which involves repainting the canvasses prepared by the artist during performance events. Covering the canvasses with paints over and over again is the most important thing about this work. These activities are deeply inspiring for curators and scholars as they prove that a work of art can last and still be subject to continual modifications at the same time. Although the responsibility of city galleries is to protect and conserve the pieces within the collection, we also have freedom to establish our own rules and procedures. Such galleries are perfect venues in which we can experiment with alternative ways of collecting modern works of art.

M.S.: Did you follow an example of any other cultural institutions while compiling the collection in this new way?

A.L.: In a way we did. When we were working on this collection I stayed in London and participated in a scholarship programme. I followed the activities of Tate Modern at that time, especially the programme of activities that took place in The Tanks, which are a permanent gallery space for live art, performances and film and video work from the Tate Collection. There is also a programme of new commissions of works made for the spaces. Another source of inspiration was definitely Biennale de Paris, which is now a biennial event and, therefore, artistic activities around it have slightly different dynamics. We also follow strategies of Polish museums, for example Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, which still collect mainly traditional works of art, despite the fact that artists develop their activities in many other directions and this is an increasingly dynamic process.

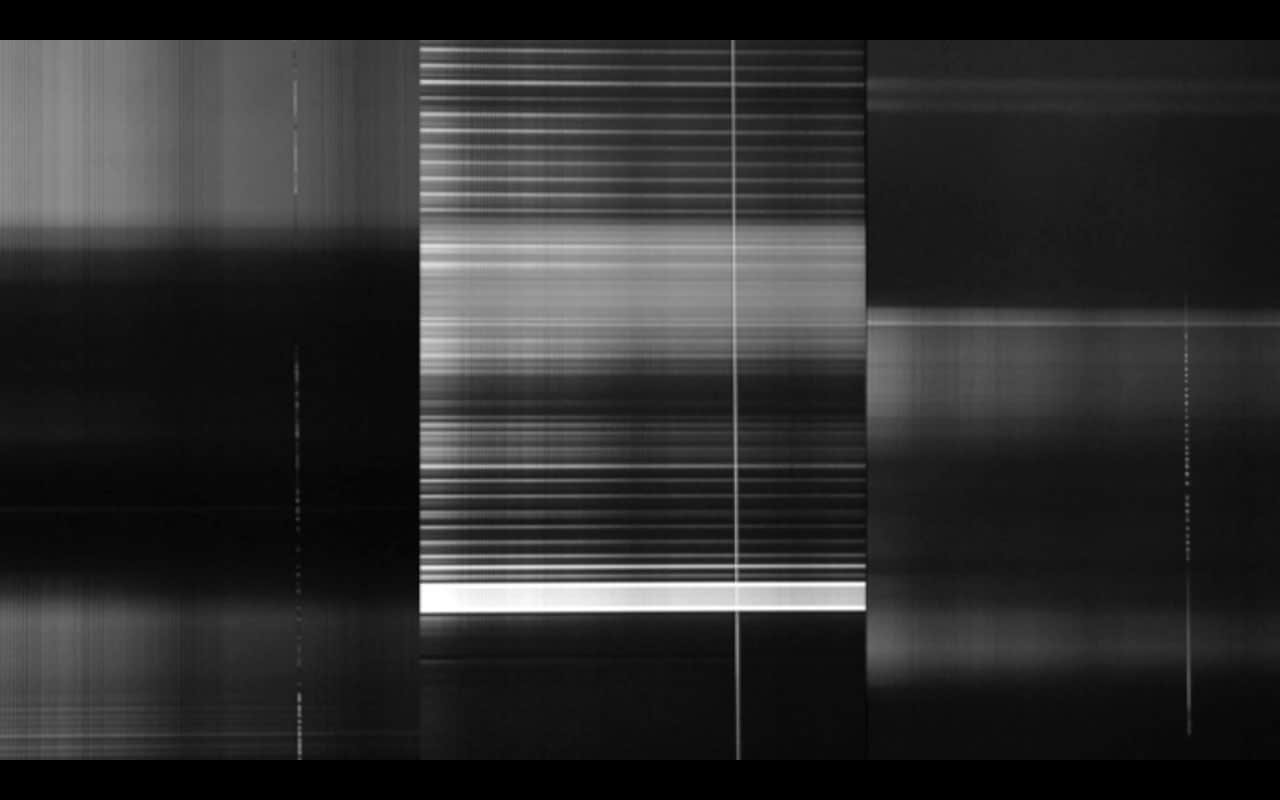

Angelika Markul, 400 milliards de planètes, 2014, courtesy: the Bunkier Sztuki Gallery, photo: FilmLove Studio

M.S.: Does this mean that your collection is not a collection of documentation in its traditional sense?

A.L.: It is definitely not. Documenting art with video materials, documents and photographs is a trend that has been developing since the 1960s. Recording works of art by these means can now be considered a classical method. What we strove for was finding the answer to the question: in what other forms can works of art be preserved?

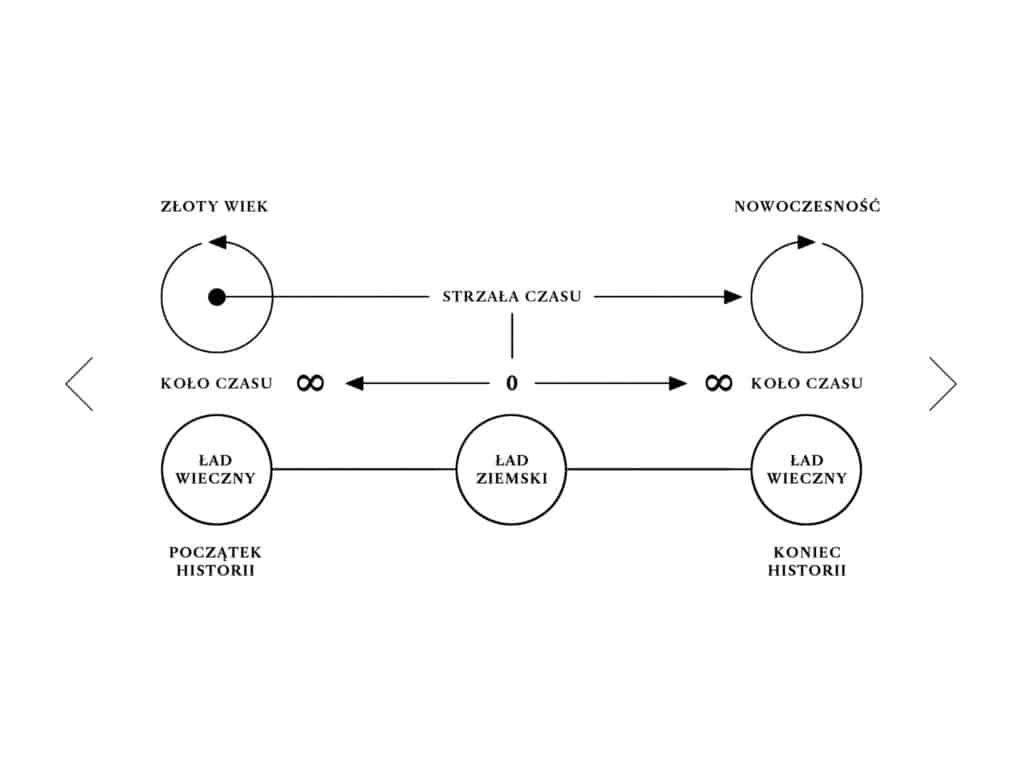

M.S.: You also started to use virtual space to present pieces from your collection, for example, a work by Jakub Woynarowski. What was the form of this work that he created called Outopos?

A.L.: This work was really experimental at the time it was created. It is an interactive diagram made available in virtual space. It is also a prototype of an online art application, which can exist no matter whether or not the gallery has a permanent venue.

M.S.: What are the most interesting site-specific works that have been presented at Bunkier Sztuki?

A.L.: One important work for us was created by Mikołaj Długosz and presented in the Bunkier foyer. It was an aerial photo of the Old Town. It effectively attracted viewers who, immediately after entering the gallery, tried to find their current location on the map. This was the first step, after which they proceeded to explore the structure of the city space. Other works that attracted attention were created by Anna Zaradny and Wojtek Puś. Anna’s work was related to the history of our gallery, the shape of the building and the architect who designed it. The accompanying sound effects adhered to the noise music convention, featuring sounds recorded in a café.

Mikołaj Długosz, Cracow- air photo, 2014, site specific, courtesy: the Bunkier Sztuki Gallery, photo: FilmLove Studio

M.S.: At a certain point in time the idea emerged to bring the collection out into the city space. Maurycy Gomulicki created an object that was placed in front of the Bunkier building. Could you tell us more about this work, which was made accessible to the audience in a public space?

A.L.: This sculpture made reference to monuments in Krakow and the Wawel Dragon. The aesthetics of the sculpture are very typical of Gomulicki’s work. There was a fantastic interplay between “The Beast” and its location. Unfortunately, we had big problems with the sculpture because it was destroyed by vandals. Later on we started to display it in spaces with more restricted access, such as the Botanical Garden and the Museum of Archeology.

M.S.: Your collection also features several murals and other interventions in the Bunkier space. Some of the pieces are placed on the front wall, for example the work by Maria Loboda. What is this work about?

A.L.: The entire gallery facade was inlayed with an enormous amount of semi-precious gemstones. The inlay referred to the legend about the Alhambra palace, according to which there were precious stones inside the walls, an indication of the power and affluence of its owners. This work transformed the gallery into a symbolic treasury or the treasure guard for gemstones hidden inside its walls.

Maria Loboda, Movements that Mattered, 2015, site specific, detail, photo: K. Marszycka, courtesy: the Bunkier Sztuki Gallery

M.S.: In recent years you acquired several works of more historic character. What was the reason for such a change of approach?

A.L.: We evaluated everything we have been doing for the last five years and thought about collecting in more general terms. We reflected on the notions of process and ephemerality not only in the context of modern art, but also in relation to historic activities. This evaluation process resulted in the acquisition of a work from the archive of Maria Pinińska-Bereś entitled Stairway to Heaven. It is a design or, to put it more precisely, a sketch of a monument – a modern mound with carved stairs and “Stairway to Heaven” inscription at the top, which could be placed in a public space. We were enraptured with the conceptual beauty of this monument and the fact that it differed so much from the things which surround us in the city space.

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, Stairway to Heaven, 60s/70s 20th century, courtesy: the Bunkier Sztuki Gallery

M.S.: What other ephemeral works and art expressing critical attitude towards institutions have you purchased?

A.L.: We, for example, bought Kippenberger cookies by Karolina Breguła, an installation referring to another famous installation by a German artist, which was destroyed by a cleaner in Ostwall Museum in Dortmund. Karolina’s installation is in fact delicious-looking cookies which prompt the audience to find an answer to a dilemma – are they allowed to eat a work of art? Can they become destroyers of a museum installation? The artist does not give them a ready answer. What she is doing is creating a situation the audience has to deal with. We archive this work as a cookie recipe, instructions and a pastry cutter.

Karolina Breguła, Kippenberger Cookies, 2012, courtesy: the Bunkier Sztuki Gallery, photo: FilmLove Studio

M.S.: There is now a lively discussion about the upcoming changes in Bunkier Sztuki e.g. the renovation and alteration of the venue, and the still uncertain merger of Bunkier Sztuki and MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art. What is the future of the collection and the institution itself?1

A.L.: We are currently negotiating the future of Bunkier Sztuki with the city and discussing the possibility of it retaining the status of an independent institution. We hope that the result of these talks will be favourable for us and during the three-year period of renovation we will be able to conduct our activities without a permanent location. We hope to focus more on activities in the city space and cooperation with local artists, the inhabitants and activists. A model example of such activities could be Manifesta or the recent dokumenta14 in Athens. We also would like to be more active when it comes to publications. For example, we are planning to sum up a stage of renovation and expansion by publishing a book, which would not be a regular catalogue. We want to invite artists to create an essay consisting of written and visual material, which would revolve around our collection. During the renovation we also are planning to focus on ephemeral activities in the city and to expand our collection with works presented in a public space, including alternative forms of monuments. In addition, we intend to make the audience more familiar with our collection by presenting it in other institutions, some of which would not be galleries or museums. The time during which our building will be renovated will give us an opportunity to engage in activities promoting the works of artists working in Krakow. We want their works to be recognizable not only across Poland, but also abroad.

Edited by Lisa Barham

1 The interview was conducted on the 15th of February 2019 during the discussion about the merger of Bunkier Sztuki and MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art. Now the director of MOCAK is also a head of Bunkier Sztuki.