The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop, Tate Modern, 17 September – 24 January 2015,photo Contemporary Lynx

Pop art, usually associated with Warhol, originated in Great Britain – as they remind us repeatedly. Perhaps this is why Tate Modern keeps on arranging similar ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions. After the great retrospectives of Hamilton (2014) Lichtenstein (2013) and Hirst (2012), this year, we have been granted a presentation of artists who are largely outside the mainstream, at least as far as London’s perspective is concerned. The curator, Jessica Morgan, took on the task of deconstructing the official narrative on the beginnings of pop art – dictated, as she suggests, mostly by New York based galleries in the mid 60s. Therefore, she deliberately defies the established history and creates an inverted picture. At The World Goes Pop, acclaimed artists like Judy Chicago and Martha Rosler are lost in a crowd of over sixty artists not known to the broader public, who created their works before the early 70s. They come from various “outskirts” – Latin America countries, Far East and Europe; still divided along the former Iron Curtain into “Western” and “Eastern” parts.

What do they have in common? It is difficult to be exact when answering this question. “A pop style or a pop spirit”, the curator explains vaguely. In practical terms, she means a collection of motifs from various fields of popular culture – film, television, press, advertisement, politics, sport, etc. It is also possible to talk about a common visual layer, very close to the aesthetics of a comic book or poster – the exhibition is full of works with simplified flattened figuration, bright artificial colours, combining text with image, using violent typography, and uniform patches and contour lines. What is interesting is that mechanical techniques (screen printing, template, etc.) generally loved by pop artists, are rare at the exhibition. It is mostly painting, sculpture, and installation. There is also a lot of plastic and other artificial materials typical of the 60s.

“Mass media, desires, and culture” – are the universal topics according to Morgan, which “must be reconsidered in their global contexts”. They cannot be defined “in a hegemonic way”; that is, in a way that colonizes – transferring ideas imposed from the position of authority. Which authority are we talking about? The power of America, generally speaking – and the various forms of imperialism, both in political and economic terms, and in a broader, cultural dimension as well. Morgan has reached for the works of artists who not only contested American policy, but went on to outright reject its triviality, known from Warhol’s, Lichtenstein’s or Wesselmann’s realizations.

Although at first sight the exhibition is full of references to American pop culture (Walt Disney’s films, pin-up girls, US Army uniforms, flags, Nixon’s or Kennedy’s images), a closer look reveals their subversive treatment. This is clearly visible in some accusatory works on the Vietnam War. In “I Want You” (1966), Marcello Nitsche from Brazil recalls a well-known gesture from James Flagg’s poster, with a small sculpture hanging from the index finger – a large drop of blood. In a series of works entitled “American Interiors” (1968), a man called Erró (Gudmundur Gudmundsson from Iceland) presents fashionably furnished interiors of American houses visited by angry Vietcong soldiers. A similar overtone can be noticed in “Divine Proportion” (1967) by Spanish duo Equido Realidad, “Sketch for the U.S. Flag” (1966) by Raimo Reinikainen from Finland and the excellent “Bombs in Love” (1962) by Austrian artist Kiki Kogelnik. Do these works change the understanding of pop art? It is hard to tell. However, they do present its American creators, who avoided direct declarations on Vietnam, in an unfavourable light.

Erró, American Interior #1, 1968. Mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna Photo: mumok © Erró/Bildrecht Wien

Kiki Kogelnik, Bombs in Love 1962, Kevin Ryan/Kiki Kogelnik, Foundation, Vienna/New York

According to Ms. Morgan’s interpretation, pop art means more than just celebrating consumption and cliché – it is about social criticism, and even political activism or the emancipation of minorities. The last part constitutes an unquestionable asset of the curator’s approach, especially where history of women is concerned. Showcasing works by over twenty mostly unknown female artists, she tests the canon of pop art which has not only been dominated by men but is at times explicitly sexist.

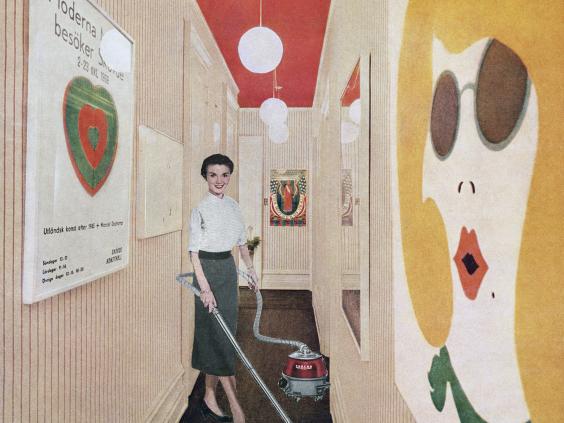

This is the theme of “Woman with Vacuum” – a witty photomontage by Martha Rosler. It shows a woman with a fake smile, vacuuming a corridor in an office building with pop art paintings hanging on the walls. The work is part of a series entitled “Body Beautiful / Body Knows No Pain” (1966-1972). Photographs of the same series can be found in the middle of the exhibition, along with dozens of realizations of artists from Argentina, Czechoslovakia, France, Spain, Iceland, Morocco and Germany that speak in one voice, mocking the stereotypical view of American lifestyle and gender roles in a family.

The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop – Martha Rosler – Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain: Woman with a Vacuum

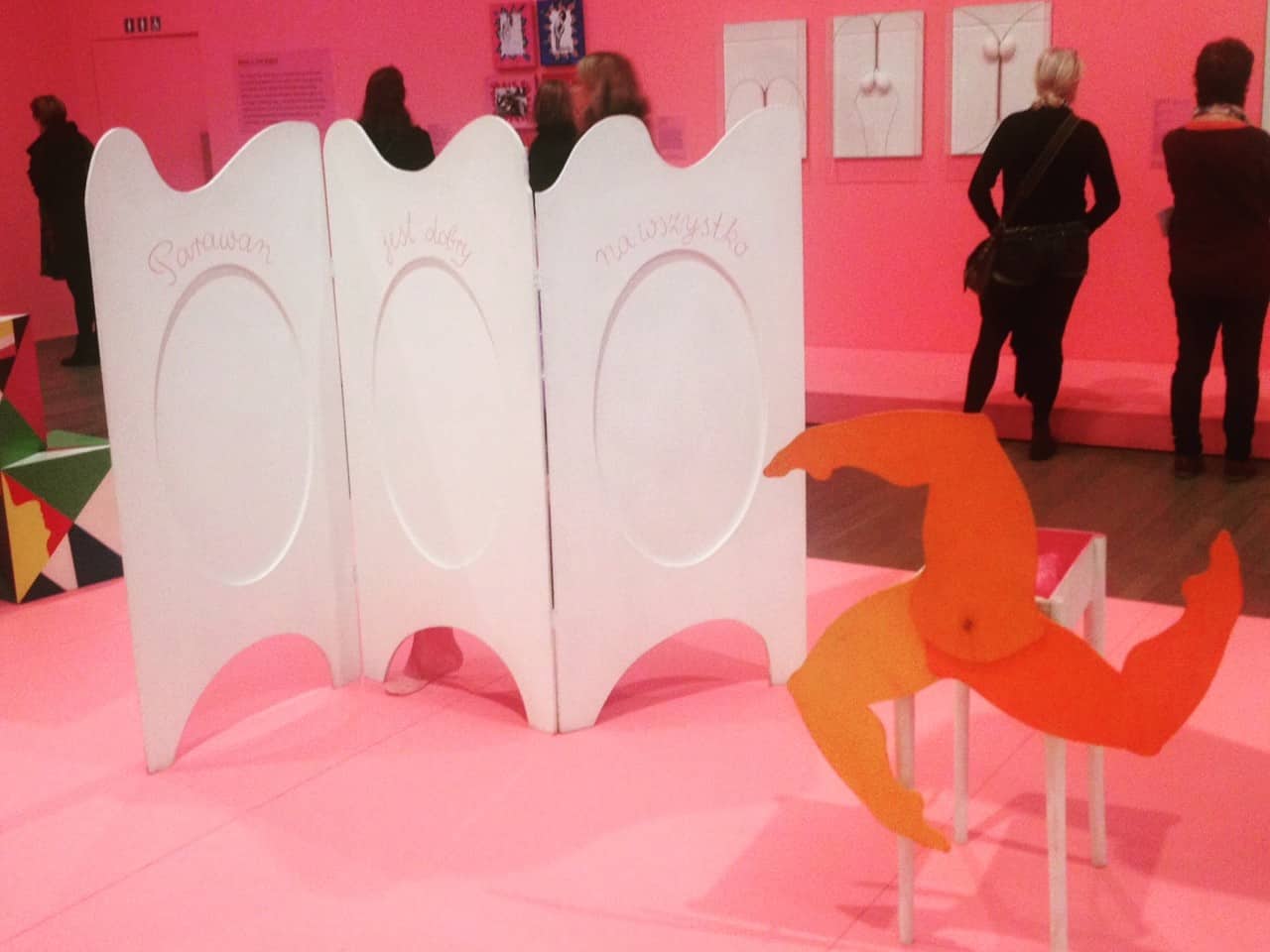

This largest and most extensive part of the exhibition passes smoothly on to the next one, focussed on reverting the ways of presenting women’s bodies that reduce her to an object of men’s desires and fantasies. Here Ms. Morgan places “Screen” (1973) and “Love Machine” (1969) – two of the most acclaimed works of Maria Pinińska-Bereś, in which the curator sees “organic, fleshy forms depicting gender differences in a patriarchal and increasingly consumerist society.” How does this relate to the artist’s stance, who famously distanced herself from feminism? It is worth consideration. It should be stressed though, that in comparison to her work, those of Renate Bertlman (Austria), Dorothée Selz (France) and Àngela García (Spain) are not as impressive as far as form is concerned.

Maria Pininska-Bereś, The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop, Tate Modern, 17 September – 24 January 2015, photo Iwo Zmyslony

The only ones that manage to defend themselves are “Hanging” (1970) by Kiki Kogelnik, with somewhat perverse latex skins, and the splendid “Little TV Woman” (1969) by Nicola L (Morocco / USA) – showing a figure resembling a rubber doll. “I am the last woman object. You can take my lips, touch my breasts, caress my stomach. But I am saying this for the last time” – this is what can be read from a flickering message displayed on a small TV set. It is interesting that the work was commissioned by Alfred van Cleef – a Paris based jeweller and was displayed for the first time in a shop window of his boutique.

Nicola L, Red Coat 1973, Collection of the artist, © Nicola L.

The presence of the well-known “Consumer Art” (1972 – 1975) by Natalia LL would be highly expected here. Yet this work was placed by Morgan in a totally different context in another part of the exhibition dedicated to “risks incurred by consumerist attitudes towards art and the commercialization of art” (“Consuming pop”). In close vicinity, there is a blue wallpaper with a motif of a laughing cow by Thomas Bayrle (1967) and a dozen logos of well-known international companies (e.g. IBM, Esso, Agfa, etc.) bluntly transformed by Croatian artist Boris Bućan. This is where the curator’s narration ends and we enter a shop where we can buy pop art bags, mugs, T-shirts and posters for prices ranging from 10 to 40 pounds. The irony of this situation seems to be intended.

Of course, mainstream pop art was neither unambiguous nor unquestioning. Glamorous, cynical, banal, though ostentatious; it usually had the element of irony, often very bitter – Warhol’s “Marilyn Diptych” springs to mind (in the Tate collection), all the more in his images of car accidents, electric chairs, race riots. Yet, the common points of reference were always consumption, the free market, excess and prosperity – things totally unfamiliar to the inhabitants of Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, Soviet Republics, Argentina, and Cuba at the time. This exhibition could have been radical there. Unfortunately, it is most disappointing here.

Experience of oppression in totalitarian system is distinctly presented in two works by Jerzy Ryszard “Jurry” Zieliński – an artist recalled by the Zderzak Gallery in Cracow a couple of years ago. “Without Revolt” (1970) is right next to the entrance and opens the exhibition. An afterimage of a pale face spread over the canvas, goggled-eyed with an open mouth. A tongue comes out of the mouth – a pillow pierced by a nail. Each eye is an eagle in front of a red sun.

Jerzy Ryszard “Jurry” Zielinski (1943-1980), Bez Buntu (Without Rebellion) 1970, Private collection, courtesy Luxembourg & Dayan© the Estate of the artist, photo Contemporary Lynx

Two rooms further, there is “The smile, or thirty years, Ha, Ha, Ha” – which incorporates the three Xs used by communist authorities to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the system on postage stamps, coins, monuments and posters. Jurry changes the X signs into three stitches on clenched white and red lips. Both works are graphically brilliant. It is no wonder that nearly all the British critics have been writing about them in their reviews, and the Tate put them in the posters promoting the exhibition. The tragic biography of the artist and the dramatic message are of secondary importance here, they are hidden, or actually lost, behind an attractive visual form.

Jerzy Ryszard “Jurry” Zielinski (1943-1980), Ha, Ha, Ha, Private collection,© the Estate of the artist, photo Contemporary Lynx

“Private Manifestation”, by Josef Jankovic, was created during the Prague Spring, when socialist realist portraits of the fathers of communism – Marx, Lenin, Stalin – were used during official manifestations in Bratislava. It is a self-portrait on canvas stuck into an anonymous figure, a crumpled shape of a human being, as if it was cut out of the crowd. It is a clear gesture of this Slovakian sculptor’s resistance to not only ideological uniformity, but also to the coarse aesthetics of authorities.

Three works from the “Post Art” series (1973) of the famous duo Komar & Melamid were showcased for no reason in the same part of the exhibition as “Consumer Art” of Natalia LL. They are charred and worn-out reproductions of well-known works by Warhol, Lichtenstein and Robert Indiana, copied from Lucy Lippard’s book (1966) intercepted in Moscow. In an ironic description, the artists explain that they presented an apocalyptic vision of the future in which works of American creators are destroyed as a result of “nuclear war or a natural or political disaster”. It sounds perverse, as the project was created in the Soviet Union when Leonid Brezhnev was in power.

The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop, © Natalia LL, Tate Modern

The World Goes Pop without a doubt aspires to be a significant exhibition. Is it going to be a turning point? Will it shape the consciousness of international audiences anew? Will it influence the change of criteria and ways of perceiving relations on the centre-outskirts axis? Let’s hope it won’t. Although an interest in art outside one’s own domain needs to be appreciated, the suggested approach is very patronizing. Presenting artists from over twenty countries, Jessica Morgan manages to create a selective and superficial image. She does not explain the criteria she applied to her choices, who was omitted and for what reason.

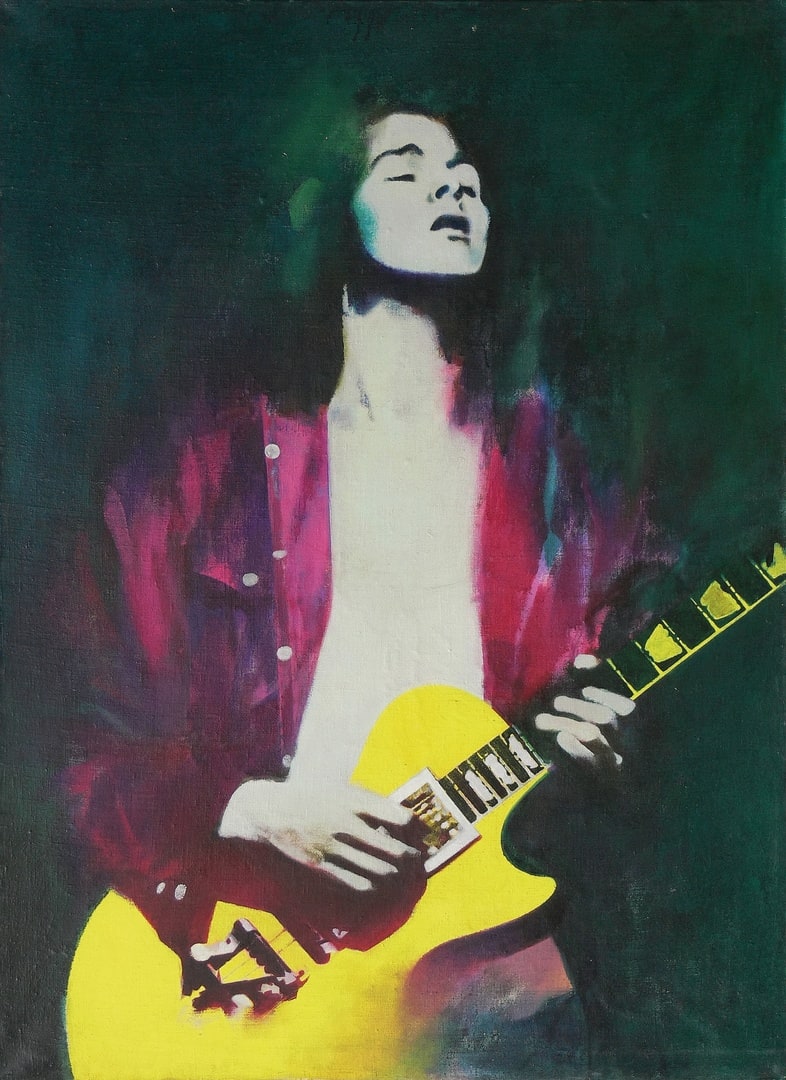

For example, it is hard to understand why mostly average works by Jana Želibska and Kornel Brudaşcu take up two separate rooms, while there being insufficient space for the still undiscovered Pauline Boty, Ed Paschke. The absence of artists from East Germany, Baltic countries or Hungary is also surprising (by the way, there is a similar exhibition on view in Budapest). As far African or Middle Eastern countries are concerned, they have not even been mentioned. Wasn’t there popular culture there in the 60s? The World Goes Pop seems to do little else but strengthen postcolonial tensions.

Cornel Brudascu, Guitarist 1970, Oil on canvas, 1300 x 960 mm, Museum of Visual Arts Galati, Romania, Photo: Szabolcs Feleky © Cornel Brudascu

But let’s focus on our “national assets”. Which artists from Poland would one present? The first thing that comes to mind is the Polish school of posters. It is true that David Crowley mentions it in the exhibition’s catalogue which recalls a miniature reproduction of the “Ty i Ja” cover (from the later period, from 1967, whereas first issues had already been published in 1959). Unfortunately, both topics are not elaborated upon in any way (see the full text here). Hence Roman Cieślewicz, the artist director of the magazine, was omitted. And speaking of him, it is hard not to consider the work of his partner Alina Szapocznikow – her sculptures of plastic would be more appropriate here than the works of such artists like Ruth Francken and Delia Cancela. Also, Władysław Hasior (you’ve never heard of him, right?) should have had his place next to Judy Chicago in a part devoted to the relation of pop art to folk art. Despite the fact that he refrained from pop art, his romantic mysticism indeed originated from instances of popular culture of the Podhale region.

I am not sure about other countries, but as far as Poland is concerned, Jessica Morgan seems not to have done her homework. This is all the more surprising as she had the perfect opportunity to do exactly that – she took part in a meeting in Łódź one and a half years ago. Frankly speaking, I believe that such exhibitions should not be organized by all-powerful institutions in the artworld, or only by a single person. It would have been better if Tate Modern had invited scholars from individual countries to cooperate and had made this project participatory and international.

Despite the curator’s words, The World Goes Pop is a demonstration of the power of the exhibition institution (Tate Modern is visited by 5 million viewers each year), and a hidden confirmation of the hegemony over the outskirts and history of art. Artists and their works – both present at the exhibition and those omitted – have been brought down to the role of hostages in a game for the right to write the history of pop art between London and New York. Feminism, political activism, anti-imperialism, are only a collection of fashionable contexts aimed at achieving a purely rhetoric effect – creating an alibi after the blockbusters mentioned above, especially after the flamboyant Pop Live exhibition (2009), where along with Warhol’s works, the names of Koons, Murakami and Hirst were listed. The World Goes Pop’s narrations of emancipation sound hollow and false after such a show like Pop Live. A tongue pierced with a nail and stiches on the lips by Ryszard Jurry Zieliński suddenly become up-to-date, although their meaning is completely different today.

Installation views of The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop, Tate Modern, 17 September – 24 January 2015 Courtesy of Tate Photography

written by Iwo Zmyślony

Biography:

Iwo Zmyślony – Studied philosophy and history of art at the Catholic University of Lublin, Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and University of Warsaw. Author of a dozen of scientific publications on epistemology and methodology of science and few dozens of reviews, essays and interviews in field of art criticism. In 2013 awarded PhD degree based on thesis on idea of tacit knowledge. Works in the field of interpretation theories, design thinking and history of art of 20th century. Cooperates with major Polish artists and art institutions. Guest lecturer in University of Warsaw, School of Form (Poznań) and Viamoda School of Fashion (Warsaw). Art critic cooperating with dwutygodnik.com and kulturaliberalna.pl.

The article was written as a part of the project “Niejawne wymiary krytyki artystycznej“, as a part of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage Scholarship.

The article was published on Dwutygodnik

The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop | Tate Modern

17 September 2015 – 24 January 2016