There is a shelf full of books neatly lined and piled up to fit in the tight space. We can see a postcard as well on the shelf, some old ticket, a souvenir brought from the last holidays which may look a bit tacky to the outsider. This is, however, unimportant, because the little souvenir brings about such a great deal of memories, as if bustling inside, waiting to be recollected again and shape us as persons… It is useless to judge a book by its cover, but maybe we can have a closer look at out own shelf – the shelf holding our past. What can you see on your “shelf with memories of the past”? Have you ever wondered what this enigmatic collection tells about you? For sure, you know how to make conclusions about what you see stacked on a shelf. When visiting your friends or family members, you definitely evaluate these people based on the objects you can see on their shelves, sometimes being unaware that you are doing so.

Adam Lee

We are all complex collections of diverse objects and ideas and the things we gather around us are an extension of what we are.

In one of his essays read out in Harvard in 1985, Italo Calvino stated that: “Every life is an encyclopedia, a library, an inventory of objects, an index of styles, where everything can be continuously mixed, combined, shuffled and reorganized in many different and possible ways”.

Following Calvino’s death, this essay became a part of “Six Memos” book, which then served as an inspiration for an exhibition with the same title, that can be currently visited at the Labirynt Gallery in Lublin. There is nothing like the beginning or the end of this exhibition and linear narration was not built either. Instead, there are two interconnected collections (displayed in two rooms) and when you look at them, you have the impression that if any two displayed works just swap places, your reception of the entire display will be just the same. The exhibition curator, Branka Benčić, refers to Calvino’s ideas in her quest for mixing and reorganizing. Changes within the exhibition are potentially possible. Maybe if you visit Lublin in two weeks and go see the collections again, the whole layout will be completely different. After all, everything is about moving and changing – us changing positions in relation to works and our reception of these works evolving as the time passes. The feeling that the exhibited pieces were randomly assigned positions in the gallery space and that they were not aligned with the neighbouring works convinces the visitors of temporary nature of the arrangement. Was it purposeful to make the exhibition look that way? Take a look at the thick black tapes separating the common space from two extremely light works by Esther Gatón, which float above the floor supported by transparent Plexiglas construction. Do you think the tapes are part of the installation or just a temporary interference of gallery staff in the exhibition space? I really do not know the answer to this question.

‘Six Memos’ exhibition

The exhibition curator encourages visitors to build a network joining them with the works, just as if they were spreading a symbolic rope. Actually, there is a proof that the rope is present between us and displayed artworks (although it is a bit too literal when juxtaposed with the whole exhibition, full of implicit meanings and understatements). You can see it in the video by Zlatko Kopljar entitled K17, in which people hold a rope between their teeth. Then we see a rope transformed into traffic routes and tunnels joining more and more parts of an anonymous city with an intricate network that enables interaction on a big scale.

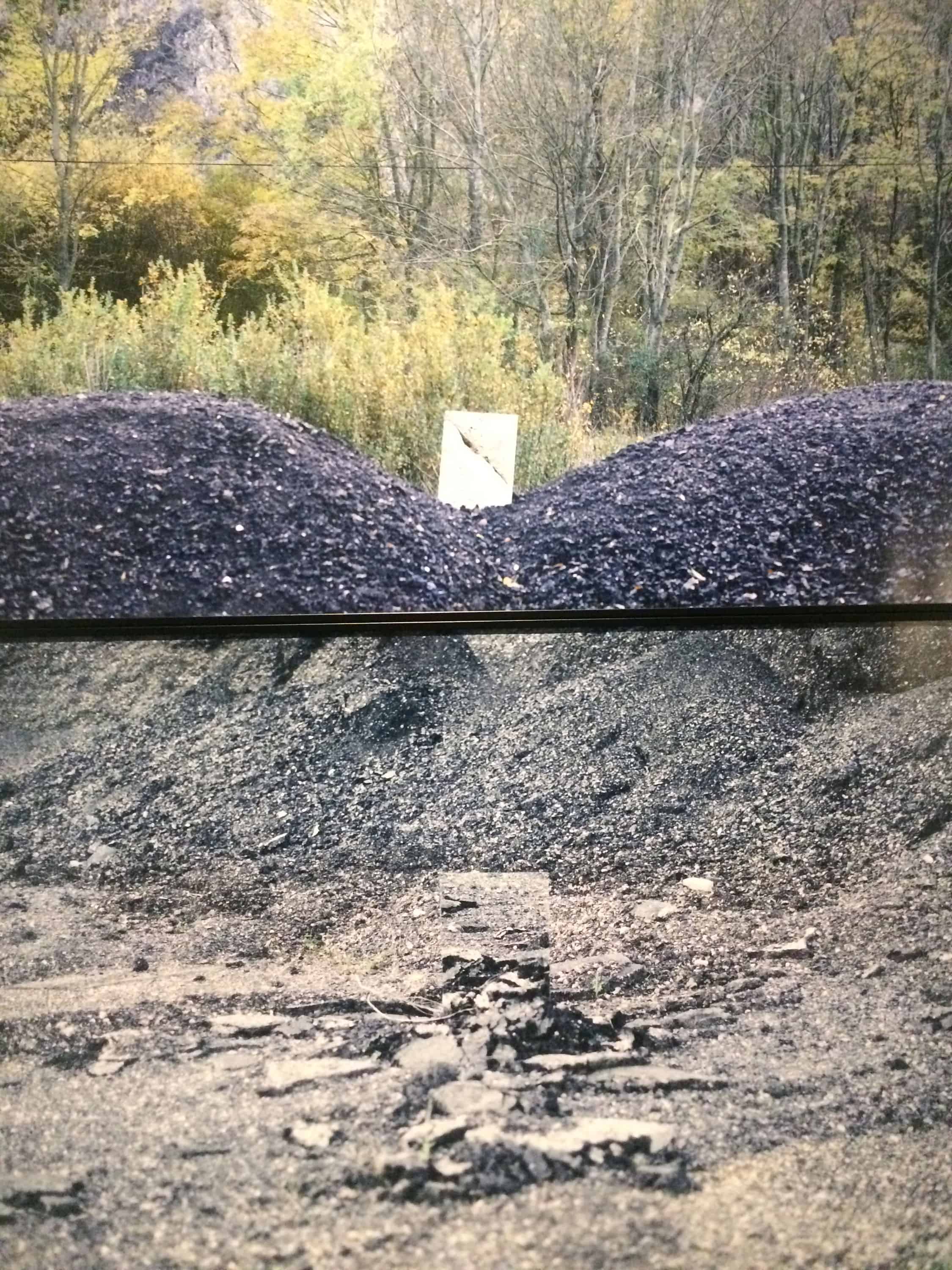

Victor Hugo Martín Caballero, Geografia Espejo (Under the Noise and Fury), photographs, digital print, 2015

I remember that, in Calvino’s opinion, the world consists of networks of various relations between people and other elements of reality which surround them. Exhibitions are usually sort of worlds on a microscale. Each artwork presents a certain part of reality – one subjective image / copy and interpretation of part of reality which the artist noticed and converted into a piece to be displayed in the exhibition space. The more important thing is, however, the meaning of the entire exhibition, namely what we see in between presented works. This is exactly what the exhibition in Lublin is about. For the audience visiting the gallery, each work is a separate entity. There is no linear narration and a story to follow. Every visitor brings out his/her own reinterpretation. The exhibition won’t tell you how to interpret what Calvino wrote. It does not answer the question of how things are now and how will they be in the future either. It is our task to try to look between what we see with our eyes. What we notice and feel “in excess” will determine our experience with the exhibition as a whole. There is only one concern related to the amount of freedom which the curator gave the audience. What about the viewers who are not familiar with Calvino’s works in detail? Will total freedom make them confused and their reception of the exhibition chaotic? The set of seemingly unrelated elements presented in gallery space can potentially be disastrous when it comes to understanding the curator’s intentions.

Tjasa Kalkan, Dialogues, colour photographs, digitally printed on archive paper, 2018

Albano Ribeiro, Calvino’s Half Dozen

Tjasa Kalkan, Dialogues, colour photographs, digitally printed on archive paper, 2018

Albano Ribeiro, Calvino’s Half Dozen

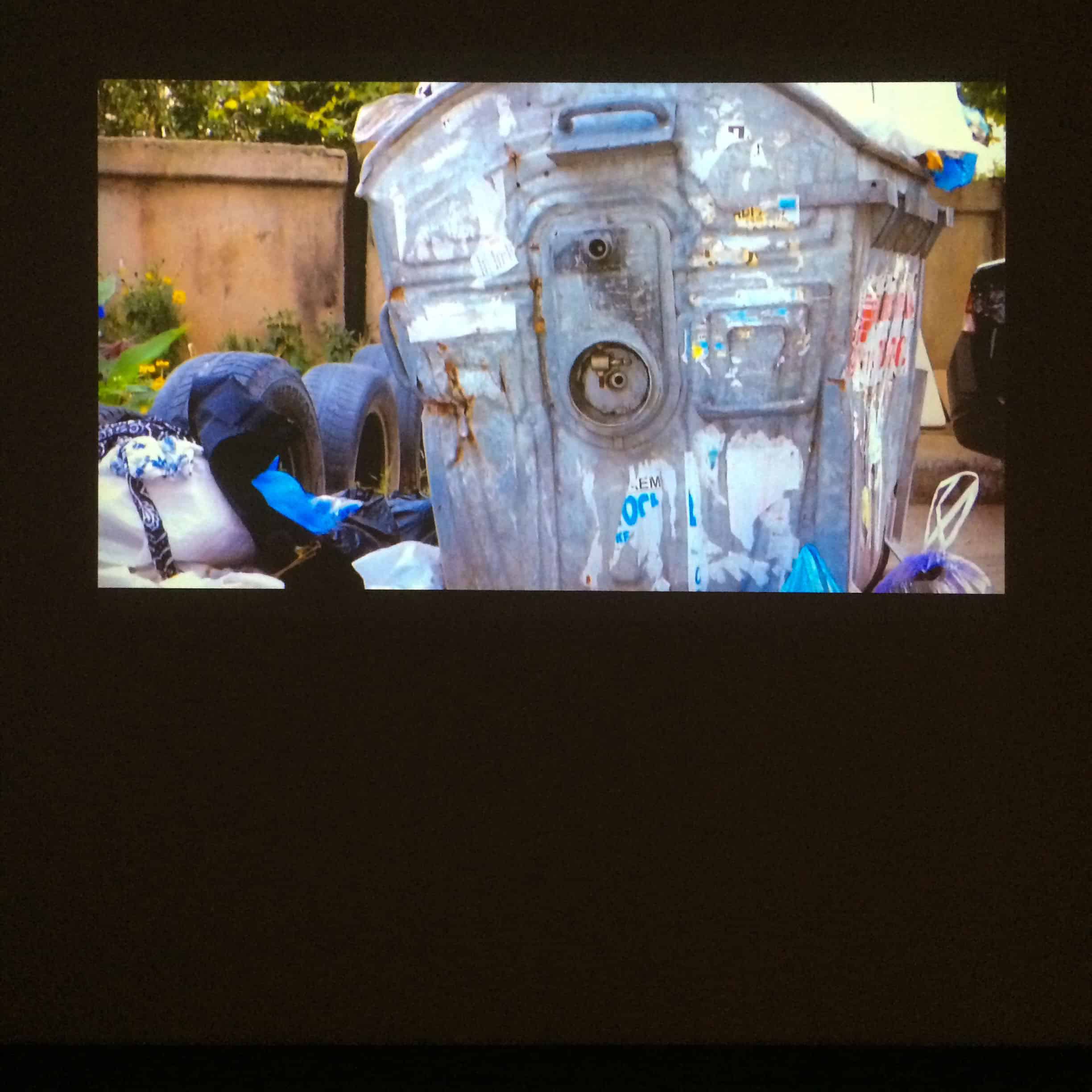

Magdalena Franczak – The scroll

We can try to challenge the last statement and admit that we live in the world which offers too much visual content and an overwhelming amount of news and photos. They totally wreck out brains, don’s they? It needs to be emphasized that we also are a collection – a collection of our experiences and of what we have seen so far. As Calvino would say, we are an index of objects. Going further, we are an aggregate of past events. We build our future on the basis of past events we lived through. Everyone is an archeologist. We dig out of our memory and analyse what we did, what we said and thought. We find images of the past in our heads. Then we act as editors or directors of the future. Our actors are things we discover in the “excavation site” and what we find available within us. We use our experiences and ourselves from yesterday, from a few minutes before. The “now” is so quickly becoming the past. It just happens within a second. We play a role in this ghost play and this is our method to adapt to the future, which will shortly become our everyday hassle. We eagerly try to make unapproachable, mechanized cities made of glass and metal more humane. This is what Tjasa Kalkan did in her works entitled Dialogues (No. 1 and 2). She added new meaning to road junctions and poles forming the border between a street and a sidewalk through unusual interventions utilizing the potential of human body. Spaces are reinterpreted. Mountains become less heavy, hard and impermeable, but much lighter at the same time, as light as the clouds. They are just a fine line, a mark (Magdalena Franczak, The Scroll). A mound of stones becomes a mirage and ephemeral mirror reflection (Victor Hugo Martín Caballero, Under the Noise and Fury). Everything is relative. A line which is just an abstract contour, when given a name can instantly become a map or, when given another name, a pattern for an outfit. Maybe a street cleaning service worker will wear such jacket while collecting waste in the city (Albano Leal Ribeiro, Calvino’s Half Dozen). Or perhaps these is a new “robe” for a president? (Pranas Griušys, The Queen’s New Clothes, The President’s New Clothes). Which president would wear it? On what occasion? Maps can show us many locations… But what would we do if there were only outlines left on our maps – the margin with numbers specifying latitude and longitude – and the picture of the territory disappeared or became defragmented (Arnaud Caquelard, At Least as Lost as Atlas)? How will we determine our place in the world in such case? It seems a nightmare – we hold a sphere or a globe in our hands that disintegrates in an instant and the pieces become less recognizable as the time passes. When our world disintegrates in such way, will the same happen to us?

It is certain that we cannot point to a single truth, one infallible authority or one world (and, consequently, one future). Each of us has their own world, so it is our task to put our souvenir shelf “in between” and fill it with everything that shapes us. Panta rei. If we manage to establish ourselves as persons right now, i.e. understand ourselves from the past, we will be able to shape our future and impact what we are now.

Galeria Labirynt in Lublin

23/11/2018 – 20/12/2018

Free admission

Participating artists: Adam Lee, Albano Leal Ribeiro, Alice Pouzet, Arnaud Caquelard, Cristina R. Vecino, Esther Gatón, Fabio Tasso, Garance Alves, Laura Robertson, Luca Arboccò, Ludomir Franczak, Magdalena Franczak, Pranas Griušys, Ricardo Suárez, Sébastien Camboulive, Tjasa Kalkan, Victor Hugo Martín Caballero, Yane Calovski and Hristina Ivanoska, Zlatko Kopljar.