Darek Fortas

Marek Wolynski: You left Poland as a teenager but later came back to explore the country and post-communist environment in your photographs. Did you feel some kind of nostalgia?

Darek Fortas: I grew up in Upper Silesia and as teenager never got a chance to meaningfully engage with the socio-cultural dimension of where I was born, so I suppose making ‘Coal Story,’ ‘Changing Rooms’ and ‘At Source’ can be seen as attempts to come to terms with my own identity which I believe was important at the time and gave me a license to move on as an artist.

MW: The photographs are deep-rooted in regional history. They touch not only on the culture of Upper Silesia and mining, but also on the Solidarity movement and the beginnings of democracy in Eastern Europe.

DF: I think that the medium of photography offers quite interesting capacity to furnish what has been made locally with more universal significance. At the time, I felt a strong desire to bring the unique identity of this region and emphasise the important role that coal mines and miners played in a wider international context.

At the same time, as part of my research as a visual artist I am interested in how the representation of conflict can be negotiated and contextualised through the lens-based mode of enquiry. What had attracted me the most before I started making them was the idea of the political potential of masses in the context of coal mines, and their significant role in resisting the communist regime at the time, which eventually lead to introducing democracy in this part of Europe.

Darek Fortas, Still Life I (Wooden Log), from the series ‘At Source’ (2013), Courtesy

the artist.

MW: Making ‘Coal Story’ must have been a demanding process. You were a photographer and researcher whilst regularly travelling between Ireland and Poland. Digging into the history and bringing to life unseen photographs formed a crucial part of the project. Eventually, you decided to juxtapose your own photographs with archive images of mines and miners taken between 1960-1980.

DF: Indeed, I decided to incorporate found archival pictures into ‘Coal Story,’ some of the photographs dated back to 1960s. They depict daily life in and around the mines in order to better contextualise the project to an international audience. I was also was very curious how each archival material would function in a context it was not initially intended for. I had a few interesting stories with some of the pictures, for instance one of them was exposed during martial law in 1981 at KWK Wujek, and the film was not processed and first prints were not made until 1989, because the photographer feared possible repercussions from communist authorities.

MW: The series brought you recognition and awards including the Camera Clara Prize and the Foam Paul Huf Award nomination. At that time, you decided to move to London and became part of the postgraduate programme in Fine Art Photography at the Royal College of Art. How did this new environment influence your perspective?

DF: I completed the last project in Upper Silesia back in 2014 and I needed new challenges to evolve as an artist, therefore I moved to London. The main driving force behind this decision was the fact that I had a strong urge to address new developments in my practice, which had emerged out of my relatively long-term engagement with projects I made in Poland. I became very interested in unpacking what is at the foundation of photography: the notion of light, presence, matter and memory, and examining the subversive value of Lens-Based mode of enquiry and how this research can potentially inform new developments in my practice.

From my perspective, successful engagement with the medium of photography in the longer term lies in operating on a certain frequency, or attaining a certain sensibility as practitioner which is then transmitted to your audience. It is difficult to describe, but I think I can compare it to the act of looking at a familiar form, or structure and then realising it is not what is seems to be. It is about the process of de-familiarisation, which in linguistics can be compared to repeating one word many times until it looses its meaning. I think this is the function of art.

MW: Do you consider de-familiarisation of the portrayed object inherent to the medium of photography?

DF: Photography exists in our culture as a paradox, as on the one hand it reinforces the idea of a truthful depiction of the surrounding world we can all conform to, while on the other side it functions as the ultimate fiction, because the subject in front of the lens as well as the photograph is undergoing a constant process of change. Therefore, it is virtually impossible to rely on the indexical capacity of the medium. The fine line, which distinguishes photography seen as a truthful and objective mode of depiction and views asserting its subversive quality on the world it represents, opens up quite an exciting territory for creative exploration and I believe this creates a niche I have been exploring for number of years now.

Darek Fortas, Still Life VI (Red Telephone), from the series ‘Coal Story’; (2011), Courtesy the artist.

Darek Fortas, Still Life IV (Sponge), from the series ‘Coal Story’; (2011), Courtesy the artist.

MW: Do you recognise the notion of melting reality with unreality as a starting point for photography or rather as its final outcome?

DF: I think narrowing down the notion of realism, or assigning a higher degree of realism to Lens-Based art – as opposed to other methods of engagement in the context of art, which don’t rely so much on the reflection of light from objects/subjects and camera as a tool in the act of creation – certainly doesn’t exhaust the conceptual ramifications of this term.

In ancient Greece, visibility represented the ultimate certainty of reality. Plato implied a natural relation between existence and truth, or the concept of reality based on an original self-presentation of beings, which can be clarified through vision. Plato’s allegory of the cave, where those who seek exposure to the truth must turn their gaze from the cave’s shadows and artificially lit world towards the sun, as the origin of what can be known.

On another note, Patrick Maynard in ‘Engine of Visualisation: Thinking Through Photography’ talks about presenting Polaroid portraits to the native tribes of New Guinea, who had neither seen photographs before nor even looked at the mirror reflections of themselves. After a very short period of time, when the tribe had become more familiar with photographic technology, it was incorporated into their own culture to the extent that they started making their own Polaroids and wore them openly on their foreheads.

I think photography has been fulfilling the hope of realness of the surrounding world, for both practitioners and the public for too long. Over the years we got used to negating the surface of the photograph and diminishing the representational capacity of the medium.

MW: Naturally, photography is a medium which allows artists to play with the representation of reality. How do you regard photography in comparison to other media?

DF: What I am trying to address is the notion of transparent immediacy and hypermediacy which seems to exist between photography and other art forms, for instance painting. Unlike a painting, a photograph does not seem to present us with a tactile barrier which results in looking at photographs as peeping through a window at the outside world. When referring to paintings, the public tend to say, for instance: ‘This is a painting of Pantheon in Rome painted by…’ but when referencing a photograph of that monument, they say: ‘This is the Pantheon in Rome’, instead of ‘This is the photographic impression of the Pantheon.’

Transparent immediacy is defined as a quality that gives spectators or users the impression that they directly experience reality instead of a representation of it. Contrary to transparent immediacy, hypermediacy refers to the quality of the artwork, which results in the spectator looking at the medium, rather than through the medium.

Darek Fortas, Portrait I (Miner After Work), from the series ‘Coal Story’; (2011), Courtesy the artist.

Darek Fortas, Portrait I (Girl in Traditional Outfit), from the series ‘At Source’; (2013), Courtesy the artist.

MW: Do you think that there is a particular approach that could be adopted towards photography as such an intangible medium?

DF: I think we need to pay closer attention to the photographic process and re-calibrate the language associated with it. What is important to emphasise is that when we invoke the camera shutter and let the reflected light hit the light sensitive surface, we create a photographic event, not a photograph. A photograph is a positive image which has a physical dimension and is produced at the very of end of the photographic process.

Identifying a photographic event has quite profound implications on the representational capacity of the medium, as in the past the mechanical means of production, deeply embedded in the photographic process, contributed to misconceptions around the lack of its intentionality, and for a long time did not allow for the medium to function in the context of fine art in tandem with painting or sculpture.

The aesthetic interest in photography lies in the photographer’s extensive and complete control over the detail that is achieved by a variety of means, which influences to a great extent the connotative process. We have put particular emphasis on the infinite creative potential, which exists as a part of the photographic event.

MW: Your latest project ‘Skene’ allows viewers to take a look at the unseen. What sparked your interest in exploring the backstages of various theatres?

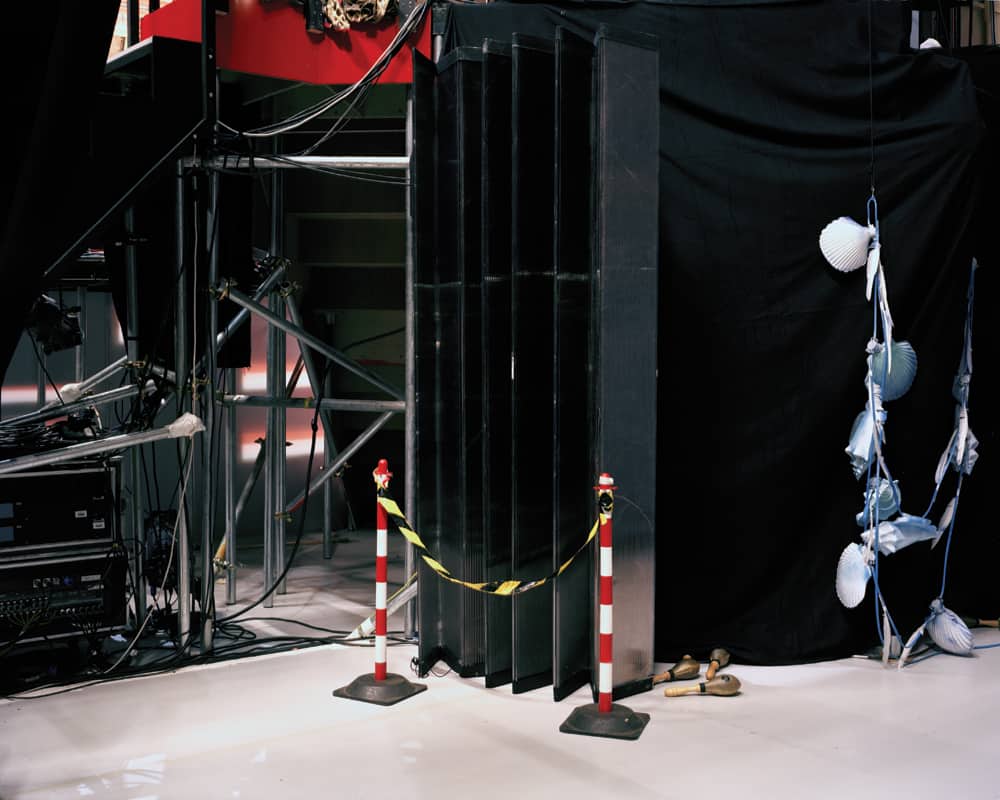

DF: Skene is a word taken from ancient Greek and literally means ‘structure that supports the background in theatre’ as well as ‘seeing and exposing’. As a part of this project I have been photographing contemporary versions of skene – structures which are crucial for plays, or performances to happen and at the same time remain invisible to public.

In ‘Skene’ I am interested in exposing the multiplicity of physical dimensions of structures which govern our sensory experience, creating a symbolic language which addresses the distribution of power within the state, and the subversive value of lens-based practice, as well as the potential of the photographic mode of enquiry to function as a mode of deconstruction.

Darek Fortas, Structure VII, from the series ‘Skene’; (2016-), Courtesy the artist.

MW: Before embarking on a journey around theatre stages, however, you travelled to Calais and spent a few days among refugees. Did the migration crisis direct your attention towards the feasible structures and the imperceptible constructions of society?

DF: After a couple of visits to Calais and its surroundings early last year, I decided to recalibrate my approach. I simply did not feel that by exploring the very critical situation around Calais that I could add anything new. It was quite a valuable research trip, though and made me realise that I should rather create a visual language which relates to what I think is a root of the problem, which I believe lies at a more institutional level.

MW: Bringing to light what usually remains invisible while paying attention to the aesthetic side remains the strongest thread in your art practice. Are you planning to continue exploring this path?

DF: ‘Skene’ is being developed as we speak; I have just arranged a visit with the Royal Academy for Dramatic Art next month. I consider it a long-term project which will in some time end up as a book. Hopefully I will get the chance to work with performing venues in other countries as well.

Currently, I am in the process of arranging the logistics behind my brand new project that is due to kick off later this year. It will be based around five locations in the British countryside. I am quite stimulated about how a lens-based mode of enquiry – especially its factual and fictitious constituents of the photographic medium – can offer means to understanding the current socio-political climate in Great Britain.

Darek Fortas is a lens-based artist with a strong interest in politics, aesthetics and distribution of power. His practice can be characterised as bridging documentary-style fieldwork with constructed studio practice while sustaining a very formal aesthetic rigour.

In 2014, Darek Fortas was announced the recipient of the Camera Clara Prize initiated by The Fondation Grésigny in Paris. He has also been shortlisted for MAC International 2014 Art Prize as a part of MAC International 2014 Biennial, Jean-Luc Lagardère Foundation Photography Bursary, BMW Residency Award at Musée Nicéphore Niépce and The Foam Paul Huf Award. His work has been published in Irish Arts Review, Source Photographic Review, Uncertain States, British Journal of Photography and variety of on-line photography blogs and magazines. Darek Fortas’ works are included in a number of public and private collections including Institut Polonais Paris, Fondation Grésigny and Pierre Passebon Gallery Paris. Work from his newest project ‘Skene’ has been recently acquired by the UK Government Art Collection.

Darek Fortas is among artists selected for Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2017 on display at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Newcastle upon Tyne, 29 September – 26 November 2017; and Block 336, London, 27 January – 3 March 2018.