Mateusz Choróbski (born 1987) is a creator of short films, spatial installations in galleries and other artistic activities that happen in public spaces. His interventions and the resulting objects are characterized by the contrast of scale, the use of found building materials, as well as the play of the existing context and minimalism of artistic means.

He now tells us about his recent stay at the residency in Italy. The brand-new program is run by Dr. Kahán Éva Foundation, the non-profit foundation created in 2015. Working primarily in the area of Central Europe, the foundation’s mission is to create opportunities for young people engaged in the creative arts as well as to support the university education of disadvantaged students. Last winter Mateusz was one of 3 artists invited to spend one month in a Tuscany-based residency. The end of his stay at the residency coincided with the closing of Italian borders and the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mateusz Choróbski

How did you find out about the residency programme? How did you apply?

I was invited by the curator Marie-Ève Lafontaine. Honestly, I am not a fan of corporate-speak which has nested in the art world and is pushing artists to use it to describe their practice, write motivation letters and apply for residencies or grants. I work with space, so the movement within it, the measurements, the relationships between one object and another play a major role in the exhibition space. How can it be described in a few sentences on an application form?

What did your regular, art residency day look like?

The Dr. Kahán Éva Foundation residency hosted me (along with two other artists) in a tiny village in the middle of Tuscany. We were surrounded by hills and forests. It was quite hard to meet anyone there (except an old man selling bread from his home, who also forced me to practice my Italian).

Just before the residency, I had finished the preparations for my solo show A Step Away in Florence. After the opening, I tried to take a breath, and the residency gave me that possibility. The slowness and the abundance of free time that I now had made me spend my time differently. That was a challenge.

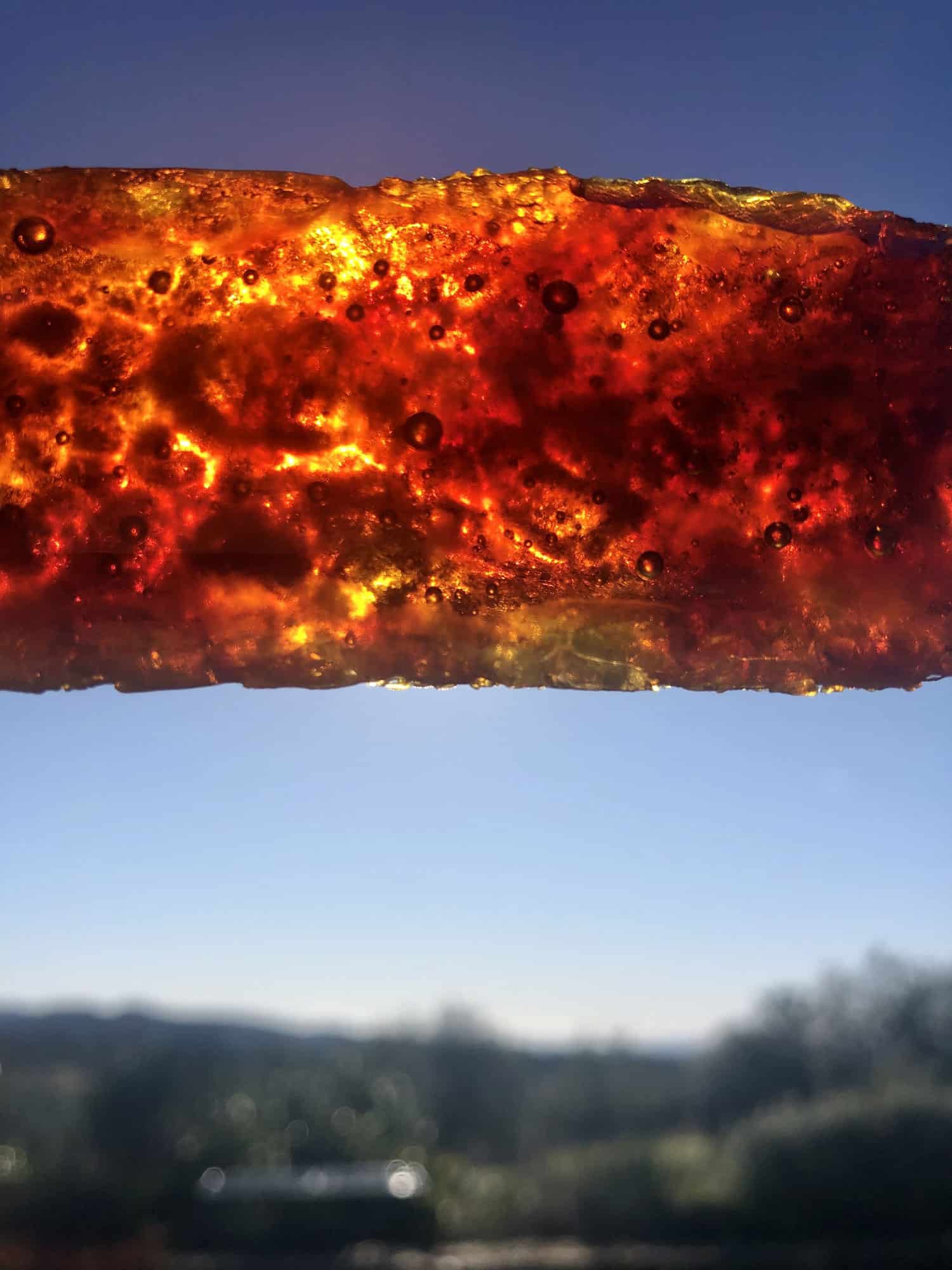

Each residency gives you a different approach. In that place, at the first glance there was hardly anything around us. But after a while, the details could be spotted. It gave us a chance to be surprised. That had a lot of value, but first, I had to allow it to happen. For example, a morning walk became my daily routine. So did wine tastings.

Tell us about the work/project that you are working on right now.

Recently, I have been working on a new sculpture for an upcoming exhibition in Venice. But because of the current situation, the work stays on paper, the exhibition is postponed, and I am spending the quarantine in my apartment in Warsaw. It is hard to predict what the future holds. I spend my days on sketching since I treat exhibition space as a singular construct, where I connect all the works into one solid artistic amalgam. I am planning the imagined shows. Sometimes it is a gallery space, but not always. For example, I am currently into commonly overlooked places. The last one that came to my mind is an exhibition dedicated to an attic space in an inhabited home. A show, that happens “above” someone’s head and lasts for an unspecified amount of time.

In your experience, what distinguishes working as part of residencies from working in your atelier?

There is no big difference. To me, both these places are like a tool. Of course, it’s good to have good quality tools, but in the end, they are only used to clarify a concept. So, I don’t attach much importance to the studio, or sanctify it. It is a working place.

I don’t think the purpose of any residency is to move the artistic process from one place to another. It is more about rethinking your daily practice, to undermine it even. New environment, the history of the place, habits of local people, distance from what is well known and potentially safe; all that can help in discovering something new. It also helps shed some light on what has been left behind.

But it is not so easy to take a step away from what is familiar and to feel like a newcomer, but not quite like a tourist. That is the real challenge of the residency; to put effort and energy into exploring the place, and also to respect it. Not to be a person with an egoistic approach, based on the emphasis of an imaginary hierarchy between him/her and a given community. This kind of thinking is short-sighted, and can sometimes transforms the possibility of real experience into entertainment, where the residency becomes a hotel without any local roots.

Do you place an emphasis on your work or rather on meeting people and exploring the city/your surrounding?

It’s all mixed up together.

What other challenges and opportunities did the residency present?

I was trying to float around during my stay there, I had no specific plan. I wanted to move freely from one village to another and find places by an accident. This is something which doesn’t happen in normal, daily life, when the plan is scheduled, and the way from home to studio becomes a routine. This is another issue – the fact that nowadays one can easily get used to something. So, the residency can be helpful in cultivating the primary experience, helps you remember what it’s like to be surprised. Which, again, can be helpful in looking for a new perspective, new configurations, being critical. It ultimately boils down to translating this experience into artistic practice and using it in thinking about one’s work.

But speaking of facts, Tuscany is a quiet place, but at the same time full of private collections and historical towns. For example, few kilometres from our residency is the Castello di Ama – a local winery with a unique collection of art. All works are site-specific realizations dedicated to the place. They are sometimes hidden, like Anish Kapoor’s piece in a former chapel, some are placed casually inside winery buildings, like Roni Horn’s piece (after staring at her work you realise the correlation between its dignified surface and the colour of the sky). It is an unusual place with great wine.

Another unpredictable thing was the coronavirus outbreak. At the beginning of my residency there were no recorded cases in Italy. But at that time the information about the COVID-19 was very limited, and nobody expected what would happen in following weeks. So, even when everybody started to talk about it and calm people around, no real awareness of threat was heard in their voices. After the residency ended, I went to Rome for a weekend. The situation changed suddenly, on Saturday everything was still normal, and on Sunday it was not. All public institutions were closed, and I was told to leave Rome and Italy as soon as possible.

Name three objects which were the most important to you during the residency.

Antibacterial gel, car and a pen.

What was the role of institution during your residency? What did it provide you with?

The institution invited me, supported my stay with the stipend and provided with the housing. I didn’t need anything else. I found it almost perfect. No one pushed me to do or go somewhere. I prefer to be left alone and spend my time as I want to. And that’s is how it was.

What would you recommend to artists going abroad for an art residency?

I don’t feel like I am a person who gives advice. It all depends on the personality; everyone has got their own way to fill their time. But in the end, I had to leave Italy as fast as possible. So, if I had to suggest something, I would say – it’s good to have an escape plan.

Mateusz Choróbski’s works have been exhibited individually: Eduardo Secci Contemporary, Florence (2020); La Fondazione, Roma (2019); Contemporary Art Center Labirynt, Lublin (2019); Wschód, Warsaw (2019); Neue Alte Brücke, Frankfurt & Union Pacific, London & Wschód, Warsaw (2018); Les Bains Douches, Alençon (2017); Kronika Centre for Contemporary Art, Bytom (2016); Contemporary Art Center Arsenał, Białystok (2015); Another Vacant Space, Berlin (2013). His works are in the collection of Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.