Katowice Street Art Festival focuses on artistic interventions in the urban landscape. Its aim is to provide every citizen with the opportunity to experience art day in, day out. The event, which has previously been held once a year, departs from its previous formula in favour of the annual long-term residency programme. In our conversation, Matylda Sałajewska, the festival’s chief curator, explains the organisers’ decision and discusses its former and upcoming editions.

Matylda Sałajewska

Anna Dziuba: How did you reach the conclusion that it was high time you’d revolutionised the structure of Katowice Street Art Festival? Why was the event, which previously lasted a couple of days, transformed into a year-long residency programme?

Matylda Sałajewska: The adopted formula had to be refreshed. The shift from the festival convention into an artist-in-residence programme has allowed artists to better explore and adapt to the space they’ve decided to work in. They had several weeks to select a spot for their art project and immerse themselves not only in the surroundings, but also to interact with members of the local community, who were engaged as consultants or participants in some of the site-specific projects in Katowice. It takes time to forge interpersonal relations and gain people’s trust. This year, a dialogue between the artist and the viewer gave rise to the art projects, which resonated strongly with our audience. While some projects were of the ephemeral and transient nature, other were permanently incorporated into the urban narrative, becoming the invariable component of its architecture and residents’ everyday lives.

Every artist had the luxury of working at their own pace and devoting as much time as they needed for the implementation of the project. Art in public spaces and quiet studio work are poles apart. I know very well from my own experience with public art projects that an assiduous exploration of the city is essential for the creation of site-specific, often interactive, pieces connected closely with the space and community. As a curator, I value the benefits of this approach.

AD: What kind of artists participated in this year’s edition of the festival? Tell me something about the projects they created.

MS: The festival opened with “Social Museum” an artistic action by Krzysztof Żwirblis, which proved that indeed, every man is an artist. The several-day-long social and creative happening by Żwirblis features a video about local residents and a temporary exhibition of objects borrowed from them, with the aim of encouraging integration between residents and unleashing their creative potential. The emphasis is placed on the assumption that every single person has their own “museum” – their own stories, memories, passions, hobbies and art creations. Knowing this, Krzysztof rifled through people’s drawers, dug out their personal treasures and hence managed to establish close and mutually trusting relationships. The artefacts were astonishing to us and, more importantly, the residents, who discovered something new about their neighbours. His findings were subsequently put on display in a primary school’s transparent corridor between the kitchen and the canteen. Consequently, you could visit the exhibition at any time of the day or night. There was actually an unusually high turnout.

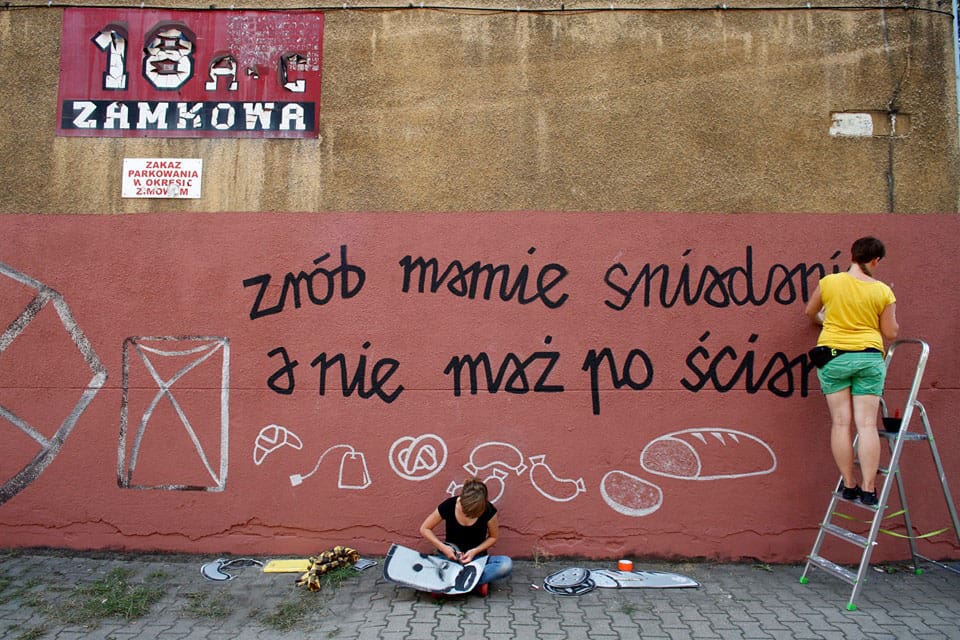

The Riposta+ duo (Ania Płachecka and Julia Biczysko) ventured in the opposite direction. Alongside the citizens of Katowice, they scoured for and pinpointed spots in dire need of social intervention. Their vision was to make a visual riposte to the places tagged with hate speech by means of its mitigation with the use of a stencil, spray or commonplace chalk. The Julianna Płaczysko combo supplied people with tools for responding to the incendiary writings on the walls, which they repurposed and reimagined. The response surpassed our expectations. After the girls completed the project, the City of Gardens was inundated with phone calls from the citizens demanding the delivery of cans of paint, buckets, brushes and stencils needed to continue the project on their own accord, which testifies to the fact that art can make an enormous difference and bridge ageist, social and cultural divisions. The results of the hard work of the mothers and daughters, who painted the facades of their blocks of flats, can be viewed until this very day.

Furthermore, “Rawa Prime Location,” Kuba Szczęsny’s project, addresses the issue of the Rawa, which is the river, which has been reduced to the irrigation channel, to put it mildly. His art installation entitled “Dom nad Ruczajem” (“House upon Ruczaj”) parodies designs peddled by marketing execs in the local property market who strive to offer unique magnificent houses and buildings in peaceful prestigious neighborhoods, pandering to the basic needs of the middle-class. What is more, Kuba intended to call the public’s attention to the river that has slipped into oblivion. In the aftermath of some turbulent historic events, the Rawa was downgraded to a polluted canal, its’ bank encased in reinforced concrete and encroached upon by the city centre. Kuba’s art project demonstrates the investment opportunities available due to the appealing infrastructure and scenery by the river, including the area’s close proximity to a body of water, a potentially enchanting view from a window, and an attractive location with close access to public transportation, as well as commercial and education facilities. The non-residential art installation’s modern design emulated the style of the so-called vanity houses, lavish extravagant residencies built in the most picturesque regions in the world. You could even enter inside to look around, read or take a nap. However, the lack of a bathroom and kitchen rendered it absurd and impractical. Still, the prized construction was the perfect place to reflect upon the self in isolation or preen around the luxurious architectural gem. We mistakenly assumed the structure would survive a few years, while in reality it lasted merely a few days. Ironically, the intense media coverage of its “mysterious disappearance” (determined by the human factor and extreme weather conditions) raised awareness about the state of the river. In spring, a slightly modified and reinforced construction will be placed by the river again. We’re relentless, determined to educate the general public and never give up! (laughs)

Kuba Szczęsny, “House upon Ruczaj”

AD: But you can’t predict whether a given project will be successful, rejected or embraced by the audience.

MS: Exactly! First of all, reaction to public art project is as random as its audience members. Street art is all-inclusive. As opposed to an art gallery visitors, your viewers stumble upon a piece on their way to work or school. We hold their opinions and observations in extremely high regard. Even greater importance is, however, attached to the exchange and dialogue conducted through an act of creation.

What is more, Michał Frydrych, another artist contributing to the Katowice Street Art Festival, made a round mobile sculpture out of processed metal that could be pushed around manually. The outer surface of the object, which ultimately signified the physical labour of miners, referred to the checked shirts worn by blue-collar workers for protection. We installed a GPS into the ball to track its location. The sculpture began its journey in Ligota (a district of Katowice) and then off it went, into the world, propelled by the strength of local citizens. The work’s title seems particularly worth mentioning – “Krople potu powróciły jak gwiazdy” (“Drops of sweat fell like stars”) evokes the faces of all those people beaded with actual sweat as they toiled (-ed since it’s all in the past) to move, to transport the round sculpture with their own hands. At some point, we lost sight of the ball, which was to be expected. The disappearance, which was presupposed in its transient ephemeral nature, is a quite common occurrence in the case of public art projects. You transfer the ownership of your art installation to the city and its citizens who breathe new life into those pieces, help them evolve and watch them fade away.

Miroslav Vayda’ visual account of his two-month residency also embodies a transience of art which strives to capture a fleeting moment. In his series of abstract paintings entitled “Częstotliwość światła” (“Light frequency”), the artist attempts to encapsulate, seize and apprehend, however temporarily, the contours, colour palate and rhythm of the city. At face value, the exhibition is the epitome of run-of-the-mill paintings portraying a single gesture when, in reality, the gallery serves a purely utilitarian purpose of providing the audience with a peaceful venue for the contemplation of works of art whose origins are ultimately out there, in the street.

Another fascinating art project by Dominik Cymer is “KTV,” the online television channel that broadcasted, for instance, Dominik’s interview with himself, an artist, traveller and iconoclast. Incidentally, these qualities describe him perfectly. The programme offers a feast of anecdotes from this year’s edition of the Festival (I don’t have to bore people with) and a straightforward uncompromising commentary about the reality. If I can say so myself, it might currently be the one and only tv-channel worth watching (laughs).

Roch Forowicz’s “Metadetails” was also among the wide variety of art projects presented during the festival. The artists drew from online resources of Google Street View to transport virtual glitches, faulty shifts and artifacts on the connecting photospheres into real-life 3D objects in 1:1 scale ratio. The result was captivating. Our usual efforts directed towards implementing the real world into its virtual counterpart were subverted. We had to draw a map for the viewers owing to a subtle and understated execution of the artworks that defy the conspicuousness, flamboyance and splendor of murals. Those works of art called for greater concentration and scrutiny. You had to stop and think and allow yourself to be amazed by your rich discoveries. His works will last, I’m sure of it. Besides, I also wonder about the influence Roch’s intervention will exert on the subsequent updates of Google Maps. A juxtaposition of one map or error with another sounds like an incredibly thrilling possibility.

Last but not the least, I’d like to touch upon the work of Tima Radia, the Russian artist we recruited after the lecture he delivered in Krakow at the invitation of the NOŚNA Foundation. Hailed as the Russian Banksy, Tima is so determined and relentless that he scoured Katowice on his own bike in search of his princess. He never found her, but he clearly learnt something. “SORRY BUT YOUR PRINCESS IS IN ANOTHER CASTLE” is the neon sign mounted on the tenement house at Słowackiego Street, reminiscent of the one featured in “Nosferatu” directed by F.W. Murnau. The artist, who already left on another one of his travels, dedicated the piece to dreamers and thus opted for a continuous soft stream of light. The project is on display until March.

In conclusion, this year’s selection included a broad spectrum of ideas and artists.

Michał Frydrych, “Drops of sweat fell like stars”

AD: You’ve anticipated my next question. I presume, as chief curator, you’re in charge of the selection process. Why can’t the artist submit their own application?

MS: During the initial trail period we placed such restrictions on the candidates. The festival’s formula was altered to give more freedom to the artists as far as acclimatisation, location and the subject of their project were concerned. We rejected the conventional open-call for artists and tested the waters. We then came to the conclusion that submissions to the second edition of the festival will be open to the artists themselves.

AD: What are the deciding factors in the selection process?

MS: Obviously, the selection is far from random. What matters the most to me, personally, is the experience in design, the creation of site-specific art projects and objects, as well as former engagement in grassroots initiatives. I expected the artist to arrive here and dig deep under the surface to unearth something phenomenal yet obscured. Katowice has a great untapped potential. There’s been some progress, sure, but our job here is not done.

The Riposta+ duo, Ania Płachecka and Julia Biczysko

AD: Did you set a deadline for the completion of art projects?

MS: Every artist was given two months to finish their project. Some worked faster, while others took their time. It all depended on the nature of their project. We didn’t impose a rigid time framework, if that’s what you mean. The festival was launched in April with the “Social Museum” project by Krzysztof Żwirglis and culminated with the final exhibition and presentation of the artbook “Dziennik Rezydencyjny 1” (“Journal From My Residency 1”), which opened at the end of the year.

AD: So as it turns out, the decision to venture into the long-term residency programme yields agreeable results. The artists are granted ample time for the painstaking consideration of their concept and an area in order to tailor their project to the needs of local community. Meanwhile, people had a noticeable impact on the execution of all projects, which they could additionally contemplate for much longer.

MS: In my opinion, a familiar space sets the perfect stage for a genuinely essential and substantial art project that could benefit permanent occupants of the aforementioned space. Until now, the artists arrived on location with the pre-produced pieces in order to assemble or install the components. Disregard for the voice of the community members and a transgression of sorts triggered a hostile reaction and emotions, which was not our intention. Those who take time to get to know each other both reap the rewards. Acquaintances are more understanding and considerate towards one another.

AD: You’ve mentioned the imminent open-call for the festival. Have you set a deadline for the applications’ submission? What kind of requirements should the application fulfill?

MS: Yes, we accept online applications to the residency programme until the 20th of February 2018. You can fill out the form and download the project’s regulations on the website we designed especially for this occasion: http://www.katowicestreetartair.pl. Our jury members include: Tomasz Konior, the architect, urbanist, founder, owner and the head architect in Konior Studio; Marta Wójcicka, head of the Studio Teatralne Koło Association (Drama Studio Circle), theatre producer and cultural events’ organiser; Artur Wabik, visual artist specialising in murals and public art installations, curator, commentator and critic; and Szymon Motyl, visual artist specialising in art installations in the public space.

Together, we’ll choose the winners whose portfolios should lay the emphasis upon the spatial, site-specific and street-art projects of a (perhaps) functional and interactive character that were created in collaboration with local residents. We don’t ask you to put forward pre-packaged artistic proposals because the idea flies in the face of our envisioned spontaneous creation on the spot. The artists should firstly arrive to Katowice and stroll along its streets.

What is more, I’m going to extend special invitations to some individual artists, and orchestrate a series of associated events and performances.

AD: Could you give us a sneak peak into the upcoming edition of Katowice Street Art Festival? Have you set a date and landed on a theme yet?

MS: Yes, the launch of the second edition of the festival is scheduled for the March 2018. After the submissions will close, we’ll take a couple of days off and then post the programme and names of the selected artists on our official website.

This year, the Street Art Festival will revolve around the notion of freedom to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Poland’s independence. Art always reflects our reality, responds to the social climate, current events and latest developments in the world. Art is not created in a vacuum. Allow me to quote Ai Wei Wei: “If my art has nothing to do with people’s pain and sorrow, what is ‘art’ for?”

In many cases, an egocentric attitude stems from one’s conviction that freedom stands for complete sovereignty. Citizens of the global village live among other increasingly self-centered distant individuals despite the ubiquity of technology, which was supposed to bring them all together. We’re free and yet lonely. An unlimited freedom weighs more heavily on people’s minds than a lack thereof. Freedom, a privilege turned demoralising burden, spawns hate speech, mutual social exclusion, intolerance, inequality or even racism.

Since Jericho, the public common space has encouraged integration, openness and unity. There are no entrance fees, gatekeepers’ preselection, numbered seats and cinema ushers. You go in to meet people face to face and own up to your genuine emotions. Second takes are frowned upon. There’s no screen and avatar that conceals your true self. The truth is the answer. These rare places are a gift. Embrace them! Now, the message we wish to convey is “go ahead, talk and connect with each other! Open up to a stranger, feel what the minority groups are feeling, empathise with their struggle and dare to say #metoo. Become more involved in whatever’s happening on your street, express your support for a common cause! Art in the public space can make a huge difference. It gives voice to the people. Our residents are the ones whose voices will be heard. I look forward to their rally!

Tima Radia, “Sorry But Your Princess is in Another Castle”