Immanuel Kant, in seeking the irrefutable foundations of unshakeable knowledge, set two separate spheres against each other – the world of things which we experience using our senses (predominantly sight) and all that which is beyond the realm of the senses, yet which we arrive at through logical thinking. He labelled the former “phenomena” – etymologically speaking – that which manifests (the Greek phainomenon), and the latter “things-in-themselves” or noumena (the Greek for mind is nous). The first of these concepts has now become a permanent part of the philosophical canon, giving birth, among other things, to the study of phenomenology (Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger). The second, however, seemed suspect from the very start, hence it was very quickly removed from broader philosophical discourse and eventually forgotten.

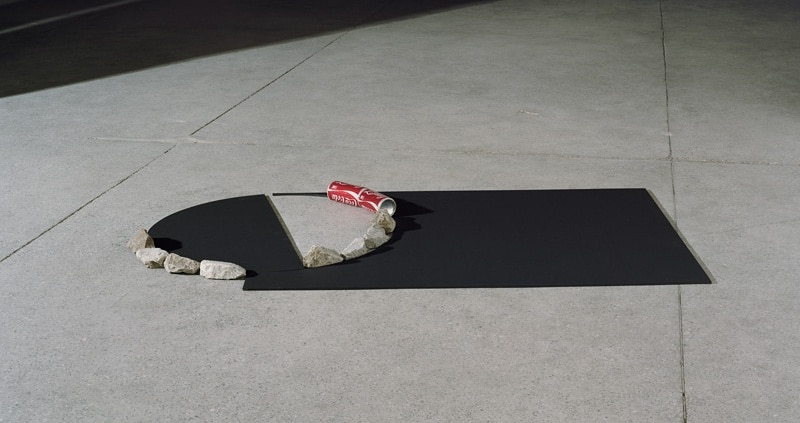

Bownik, Untitled, 90 cm x 110 cm, 2013

We are referencing The Kantian differentiation here as a sort of conceptual item which will not only help us appreciate the conceptual complexity of the works of Pawel Bownik, but we can also use to then ask several questions about the current status of photography as a whole. Today, it seems, due to the widespread use of new technologies, we are more and more often thinking of photography only in terms of that which can be seen – the flat image to be enjoyed whether it is found in a “white cube” gallery, printed on shiny paper in a coffee table book or scrolling across a smartphone screen. We feel no difference between any of these contexts, forgetting about that which has meaning, yet remains inaccessible to the human eye.

Bownik, Adaptation 1, 100×189 cm, 2015

Today, it seems, due to the widespread use of new technologies, we are more and more often thinking of photography only in terms of that which can be seen – the flat image to be enjoyed whether it is found in a “white cube” gallery, printed on shiny paper in a coffee table book or scrolling across a smartphone screen. We feel no difference between any of these contexts, forgetting about that which has meaning, yet remains inaccessible to the human eye.

Meanwhile, photography is not just represented by images, but also by solid objects and a whole host of processes involved in the art of capturing light – both these aspects equally invisible. For about hundred and fifty years since its invention, photography represented the synthesis of both these dimensions – a sort of “thing-in-itself”. Only when the two met did the visual phenomena appear.

For a century and a half, it wasn’t just about how to frame a shot, one’s reflexes or ingenuity, but above all about your technical abilities and skill in laborious operations involving light-sensitive materials; about the marriage of craftsmanship and alchemical knowledge. Daguerreotype, Cyanotype, collodion, rubber, albumin, bromoil, and then polaroid, cibachrome or transparencies – each one of these historical techniques was something specific, each had its own, separate material nature, was subject to utterly unique processes and had very different effects on the viewers.

Bownik, Passage 140cm x 240cm 2013

For a century and a half, it wasn’t just about how to frame a shot, one’s reflexes or ingenuity, but above all about your technical abilities and skill in laborious operations involving light-sensitive materials; about the marriage of craftsmanship and alchemical knowledge.

During the last two decades, digital photography has changed these considerations. The photographic image has become a visual fetish – something as equally intangible as a web page, a text message or an email. Instead of using traditional film, glass or paper, today photographs tend to exist in some sort of “clouds” – beyond space and time, in virtual drives – ergo, both everywhere and nowhere.

Hence, it may be time to stop and consider: have we not missed something? Has interest in the aesthetic, political and semiotic functions of photography not blinded us from perceiving a vital aspect of its identity?

Does the identity of photography exist at all? Something unchangeable in time, applicable to all of its genres? Or is the opposite true? The word “photography” is an open concept, part of a linguistic game, while individual objects named in this way are not connected by shared characteristics, only by a form of Wittgensteinian family resemblance?

To what extent have digital formats changed photography? Why do we treat them as something neutral? Or perhaps in a “post-media” age (Félix Guattari, Lev Manovich, Rosalind Krauss) materiality no longer has any meaning?

The processes of successive dematerialisation of images have, of course, been analysed by Jean Baudrillard, who looked for the inevitable consequence of mechanisms of mass reproduction. His stance can also be interpreted as a kind of post-Marxist variation of Kant’s idealism – because simulacra act upon us in ways which are autonomous, creating a “hyperreality” from which we cannot escape – there is no “outside” or “things-in-themselves”.

The French theorist did formulate his opinions in a totally different context – the days of the growth of television, billboards and colour-printed press, a long time before the birth of the internet and mobile tech. Hence today, as conventional media goes into a steady decline (while we simultaneously witness the birth of something completely new, yet completely undefined), the questions previously asked about photography should be posed anew. At present, they no longer relate solely to the language of our media, but the basic links in the chain which binds our societies and our identities together.

Bownik, The tenth Day of Summer, 150 x 122 cm, 2013

The works by Paweł Bownik allow us to interrogate the essence of photography otherwise hidden from conventional sight – to cross the horizon of flat visuality.

The works by Paweł Bownik allow us to interrogate the essence of photography otherwise hidden from conventional sight – to cross the horizon of flat visuality. And yet they conceal their layered nature even deeper, the more they seduce us with their visual power – a clear, cool, analytical form of beauty. This isn’t, however, a mere costume, a game being played with the human eye – with our desire to experience luxury, order and symmetry. It is also an allusion to fashionable snapshots of modernity. Hollywood glam, pomp, kitsch, ostentation, the aesthetics of pack shots, police archives or fashion photography – all of these are quotes; scraps or afterimages of a Baudrillardesque “hyperreality”.

Bownik’s photography begins elsewhere, in a place which cannot be seen – in his Warsaw workshop. This is above all a dull, lengthy process. The artist specifically chooses to work in different media, skilfully using analogue techniques in exposing and developing negatives and darkroom postproduction. He takes most of his photos with a huge 8×11 inch format camera, on single-use negative and positive plates produced by either Fujifilm or Kodak. This sort of method demands rigorous discipline and superbly honed skills. The shots must be pre-prepared down to the tiniest detail, because there is practically no chance at all of correcting or repeating them afterwards.

Bownik, Den 140cm x 209cm 2014

Bownik, Grid, 112 x 92 cm, 2012

The best example of this is Legowisko (2015) or Krata (2013). Much like the works by Jeff Wall or the Düsseldorf School (Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer), everything here is subject to laborious, precise, conscious arrangement – starting with the construction of complex, work-intensive scenographies, through to arranging lights, careful choice of optics, framing and composing of shots, and finally on working with his models, the minutiae of their make up and costumes.

In his Untitled (2015), it is the process itself which becomes the subject of his work. A simple motif, at first appearing to be frustratingly banal, hides within itself a puzzle about the very foundations of how photography is created. It becomes a silent haiku about the complex relationship between light and darkness; about that which can be seen, and why, and that which cannot; about the paradoxical dynamic between the background and the figure; between abstraction and representation; between the surface and perspective. Intellectual complexity is here contrasted with an extremely ascetic, minimalistic form.

And so photography is not just the image, but above all the process and its production – the physical product. Bownik is also consciously operating in this dimension. He treats his works in a very physical sense, like sculpting almost.

Bownik, The tenth Day of Summer, 150×122 cm, 2013

And so photography is not just the image, but above all the process and its production – the physical product. Bownik is also consciously operating in this dimension. He treats his works in a very physical sense, like sculpting almost. Everything has a role to play here – the scale, the surface of the image, the frame and its thickness, its location in space and the way in which it is shown; how individual images are arranged next to one another and how they interact in terms of contrast or completion. It forces not just our eye into movement, but also our bodies – these photographs tend to keep us at arm’s length, forcing us back. Through this very effect they enter into a long-standing tradition of painting and categories such as allegory, symbol, pathos or decorum.

And dialogue is in Bownik’s work completely self-aware, though he conducts it through images, not words. This seems to be the most interesting aspect of his creativity. A trained eye can see here a range of discreet references to numerous toposes from visual culture – the history of painting, film, advert or photography. My favourite example is the series E-Słodowy (2010-12), which is a continuation of an earlier project – reportage focused on the world of professional video games players. As he was creating the project, the artist noticed that alongside all of the advanced technology, the players also constructed a range of products in the spirit of “DIY culture”. He began documenting them with his camera, but in such as way as to echo the work of Russian constructivist painters.

Another example is the remarkable project Dissasembly (2014), in which Bownik references the works of artists such as Karl Blossfeldt, Nobuyoshi Araki and Robert Mapplethorpe – everything with the aid of light and composition. But the process is of real importance in this case also – meaning that which cannot be seen. The titular “disassembly” is, after all, a complicated process, and being even more precise – a whole series of processes. Each of the flowers which appear in the images has been disassembled, literally taken apart, and then subjected to a reverse reconstruction – carefully pieced together with the aid of rubber bands, sellotapes, pins, post-it notes (an ironic allusion to the currently fashionable corporate aesthetic). In this way, a range of ill-complete and ambivalent objects have been created, hypnotising with their maimed beauty. Just by the way they look they pose questions about their origins, and the only answers which come to mind must awaken both ethical and aesthetic conflicts.

Bownik, Disassembly, 88x100cm, 2014

We are also here looking beyond the image, into the very depths of the nature of photography. “It seems to me that nature, as punishment for our attempts to uncover its secrets, is trying to show us the face of death” – this sentence comes from Charles Paul de Kock in 1842. Susan Sontag has also written about the relationship between death and photography, fascinated by the cognitive dissonance between the illusion of a captured moment and the awareness of irreversible loss; between the instant illusion of the living presence and the actual lifelessness of that which we perceive. Roland Barthes insisted that it is through photography – rather than through philosophy or religion – that modern man contemplates death and the ruthless, continual passing of time.

Hence, in fact, we make our way back to Kant: does time indeed flow, or is it simply a form of perception? Is there anything beyond time? What sort of “beyond” are we asking about? Are we free, or is it merely an illusion? What constitutes this freedom? Or morality? Am I working in line with a set of rules which I would like to turn into a universally binding set of laws? Is something beautiful because it appeals to me, or rather the reverse – it appeals to me because it has beauty in itself?

The anachronistic figure of the philosopher from Königsberg presents us with an intriguing counterpoint, or even a specific sort of negative, for the commonplace figure of the post-modern cosmopolitan person (hipster?). Although we have long ago lost faith in the mind, so very beloved of the Enlightenment period (in turn uncritically surrendered to technologies), new philosophical questions continue to trouble us. Today, in the age of distraction and over-stimulation, of desiring and endless longings, of the blurring of borders, of wandering from one place to another in the search for experiences, perspectives, some sort of sense, of escape – they are what leads us back to things in themselves. Yet unlike the days of Kant, we are no longer expecting a singular answer. We are interested solely in contemplating the problem in itself. It seems possible, in fact, that in this sense we are actually wiser.

Written by Iwo Zmyślony

Translated by Marek Kazmierski

BOWNIK is a photo exhibition during the Duesseldorf Photo Weekend 12 – 14 February 2016

Gallery of the Polish Institute in Düsseldorf, Citadellstr. 7, 40213 Düsseldorf

Opening: Friday, 29 January 2016, 7 pm

Duration: 2 Feburary – 3 March 2016, find out more here

Bownik, Worm 140m x 217cm 2014

Bownik Untitled, 110 cm x 170 cm 2015