The nineteenth-century changed the world beyond recognition. Manual labour was relinquished and replaced by the machine, people began to travel on an unprecedented scale, doctors peered non-invasively beneath the skin whilst the theory of evolution suddenly and unexpectedly shed light upon our past. This was the century that changed man’s perception of almost everything, and the inventions of the period were the foundations to many of the greatest changes humans have seen. But the industrial revolution was only the beginning, and what back then seemed foreign and futuristic has invariably become integral to modern-day life.

Piotr Krzymowski, “Before and after”, Homo cellularis exhibition, Toruń, 2019, photo by Dawid Paweł Lewandowski

Piotr Krzymowski’s exhibition at the CoCA in Toruń draws attention to the fact that technology has become intrinsically linked with our everyday lives, subliminally and invasively informing or pre-empting our every move. The term Homo cellularis was coined by the Italian sociologist and philosopher Maurizio Ferraris whilst analysing people’s relationship with their smartphones. His findings suggest that these devices have become an inseparable extension of both our minds and bodies. As a result, virtual reality becomes our parallel world, seemingly intangible but very much present and plausible in the minds of users. Thanks to an omnipresent network, we’re able to answer almost any question on the spot. Instant communication has become accessible to all, those who consider themselves excluded from society are able to connect with seemingly like-minded users worldwide and traditionally elitist institutions and museums are digitising their collections and opening up their archives to the world. Whilst instant and virtually unrestricted access to data allows for wider research, facts are dispersed within a sea of fake news, open to endless alteration and reinterpretation. As a result, reputations can be made or unmade in minutes as scandal spreads like wildfire. A sensationalist headline may last only minutes, but once shared its repercussions may seem indelible. However, given the number of apparently noteworthy individuals and the voyeuristic tendencies of our generation, a more scandalous affair is always on the horizon. Furthermore, today’s language is visual, dominated by the immediacy of images shared on Instagram, Facebook and other such portals. For an ever growing sector, the foremost functions of a smartphone are to take a great picture and publish it instantly. Mobile applications with endless filters and professional quality retouching tools can enhance the human body beyond recognition. They eventually create an avatar version of their user, which, taking on an ever more manipulated form, begins to live its own life. All of this urged the artist Piotr Krzymowski to look objectively and critically at the ever-changing world around us and present an unadulterated vision of the near future.

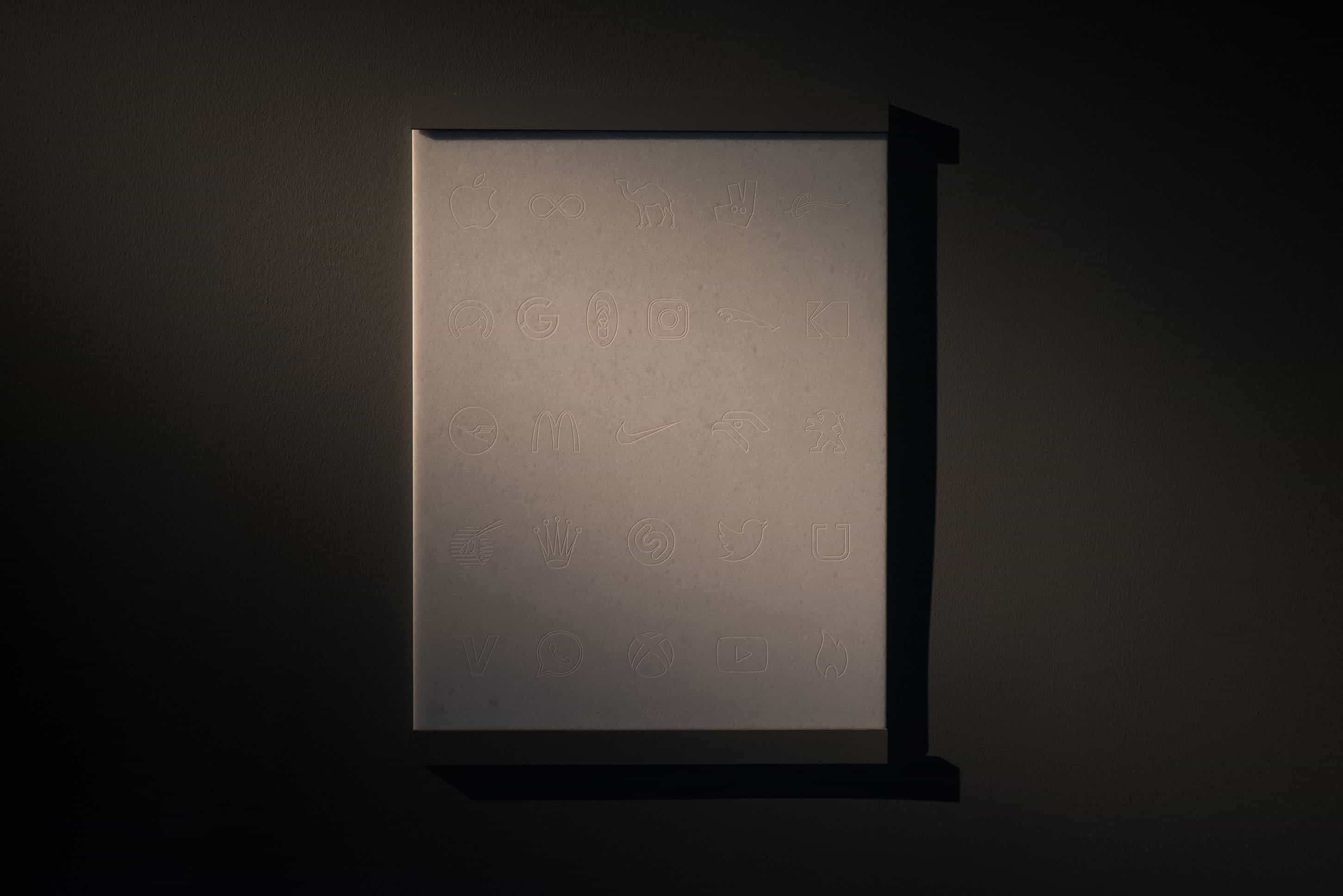

Apple-Zippo, laser engraving on marble, 90 x 70 cm, 2017, Homo cellularis exhibition, Toruń, 2019, photo by Dawid Paweł Lewandowski

In ancient civilisations stone was the foremost carrier of thoughts. It conveyed early sayings, presented images of heroic figures, recorded important events and mythical scenes. In time it crumbled; through war, inclement conditions, a change in beliefs, religion or political views, symbolising the collapse of one epoch and the emergence of a new one. As a result, stone can be seen as the carrier of memories. In 2017, Krzymowski created the work entitled Apple-Zippo, a laser-inscribed rectangular block of white Greek marble. Upon it the logos of the most searched companies and most downloaded mobile applications in English-speaking countries are engraved using highly advanced laser-cutting techniques. Historically, influential families had their coats of arms sculpted, etched and engraved. Some researchers observe that today these symbols of power have been replaced with company logos. By engraving them in stone, the artist elevates them to the rank of artworks, immortalised and protected from oblivion. The work serves as a modern-day inscription table, which through pictograms replaces powerful families with powerful brands. Once more, the surface of the stone becomes the carrier of information, stopping time to depict the hieroglyphs of our age.

Piotr Krzymowski, a touch too much, a series of screen-prints illustrating fingerprints collected from the surface of artist’s iPhone screen, thermochromic ink on paper, 150 x 80 cm, 2019, Homo cellularis exhibition, Toruń, 2019, photo by Dawid Paweł Lewandowski

A further body of work which references the memory of materials is a series of screen prints from 2019 entitled a touch too much. According to statistics, the average smartphone user reaches for their phone every 6.5 minutes, touching the screen an average of 5600 times per day. Over the course of a week, every evening the artist covered his iPhone screen with aluminium powder. Usually reserved for criminologists, the powder uncovers the daily journey of his fingers upon the surface of the phone. The artist scanned the resultant images, records of the marks, scratches, fingerprints and dust accumulated on the screen’s surface. Whilst collecting these images, Krzymowski establishes an extraordinary relationship between two electronic devices, using the scanner as a photographic tool to uncover a snapshot of hidden information that is in constant change. Focusing on the phone’s “space of operation” the artist reveals a tapestry of spontaneous, tactile gestures seemingly deprived of any formal criteria. In reality though, this unique combination of actions records movements made with clear logic and a decisive objective: each image corresponds to a specific moment of interaction with digitised information. In addition, the works are printed using a rare thermochromic ink that reacts to heat and disappears once in contact with the human body. By interacting with the work, viewers leave their very own fleeting trace, highlighting the transience of human presence in the digital era. Twenty-first Century consumers generally give little importance to the lifespan of their technology, since new models of virtually everything are continuously emerging on the market. As a result, traces of their presence will only last until the next upgrade. Krzymowski’s installation entitled 26.5 meters per day brings to the fore a further consideration. The artwork, which consists of old rulers hung on the wall at eye-level, illustrates the average distance fingers travel each day by scrolling through data and images on a smartphone. The meterage is illustrated in order for the viewer to visualise the route in real time and space with his own body. The use of old measuring objects once again refers to the analogue predecessors of modern technology.

Piotr Krzymowski, 29.10.17, 1:51PM – 30.10.17, 1:51PM, Instagram Story @markvandelli: pixels converted to grains of sand contained within hourglass, 50 x 20 x 20 cm, 2017, Homo cellularis exhibition, Toruń, 2019, photo by Dawid Paweł Lewandowski

“Human beings are evolving into something different. We are becoming a hybrid species – a fusion of biology and technology. The same tools that today live outside our bodies – smartphones, hearing aids, reading glasses, most pharmaceuticals – in fifty years will be incorporated into our bodies to such an extent that we will no longer be able to consider ourselves Homo sapiens.”

This era saturated with visual stimuli has resulted in a ceaseless quest for avatar-perfection, no matter how far removed from its human counterpart. The disparity, and ultimate unattainability, has been proven to cause depression, notably amongst a younger, more sensitive generation. It might be said that where an obsession begins with digital manipulation, it ends under the scalpel. Rates of suicide as a direct result of the internet and cyber-hate are growing at record pace. In Krzymowski’s next body of work, the artist observes a growing trend for Instagram-frames: decorative boards placed in touristic locations that entice passers-by to take pictures against a preselected backdrop. All one has to do is stand in the right place and take a selfie. Hashtags (keywords that help one search for specific content on the internet) are provided so as to ensure the subject annotates their post correctly – providing maximum visibility for the advertiser. Taking a photograph has become so customary that little if any attention is paid to the quality of the image being shot. Krzymowski taps into the phenomenon in a sequence of analogue slides titled #. Typically “hashtaggable” tourist destinations or landmarks provide the backdrop to a series of portraits of his hands in which he forms the hashtag symbol. By asking passersby to take the photographs for him, he makes these strangers co-authors of the works. In many cases people were entirely unfamiliar with analogue technology, expecting to find a screen with thumbnails on the 1970s Zenit camera used in the series. The symbol of the hashtag, with its immediacy and inherent digital connotations, collides here with the ritualistic, time consuming and oft unsuccessful act of analogue photography. Many believe the internet to be a reflection of our times. In 1977 the song Alphabet by Amanda Lear was released with immediate success. The melody was largely based on fragments of Prelude and Fugue in C major BWV 846 by Jan Sebastian Bach. The text was written by Lear herself and has a distinct autobiographical character. In it she recounts her association with each individual letter of the alphabet. The song resonated with Krzymowski for its timelessness, whilst being invariably rooted within a specific moment in time. It became the background for his video work Alphabet (after Amanda Lear), in which the artist superimposes his own internet searches to Lear’s composition. The resultant work is a topical story about “The alphabet of my generation”. Google searches reveal familiar words such as: BBC, Google Maps, Amazon, iPhone 7, Tesco, YouTube and Zara. Search engines use algorithms that help pre-empt what one types, providing an unprecedented insight into the twenty-first Century mind. It allows one to monitor trends, concerns, interests and more in real time, painting an evermore accurate picture of modern-day man. The exhibition presents three works that reflect upon the particularly negative aspects of the web. When Alexa met Google Home and Siri is a video installation featuring an imaginary conversation between the three most used voice virtual assistants. The characters initially exchange views on trivial, superficial matters, until their conversation develops and begins to cover topics no robot has questioned; emotions, religion, politics and typically existential questions. Their appearance is conventionally robotic, and the heroes of this installation emphasise they were created as mere assistants, unequipped with the ability to think in an existential way. The characters know the definition of feelings but are unable to introduce such concepts to the virtual life. These three figures are a great example of unsuccessful attempts to create a friend, a helper, invented to assist internet users to find themselves in the depths of the net. Even though they seem curious about the issues human beings may experience, their service is based on generic algorithms and calculations – if only because a computer-based avatar cannot generate real feelings. A virtual character cannot replace a friend because he lacks empathy, emotion or commitment. At first glance, a funny conversation between three assistants reveals the difficult truth about the impotence of the virtual world. A dispute reminiscent of carefree conversations between children sometimes morphs into discussions of a scientific nature, where answers, definitions and calculations are retrieved automatically by the search engines on the web.

Piotr Krzymowski, “Alphabet” (after Amanda Lear), video installation, Homo cellularis exhibition, Toruń, 2019, photo by Dawid Paweł Lewandowski

A plethora of existential issues arise when considering social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. Users are invited to create profiles which record every aspect of their lives; from religious and political views to relationships, work, family and travel, supplemented with an endless stream of photos, videos and comments. But what happens when one dies? The answer to this question can be found very quickly on the web. Facebook for example suggests converting a normal account to a memorial account for the deceased. Once a family member uploads a copy of the death certificate, the appropriate information appears next to their profile. However, very often this doesn’t occur and strange phenomena begin to appear. Absurd situations such as people posting birthday wishes on the profiles of deceased friends as a result of a Facebook reminder may appear. The theme of death in the digital age appears in Krzymowski’s work, notably in @paulomacareno from 2019. The installation, which culminates to take the form of an urn, has an interestingly performative nature. After the artist’s friend’s death, Krzymowski had all the photographs posted on his Instagram account printed. Pictures that presented the story of a real human life (if slightly adjusted, as is often the case online), were made 2D on paper, and then cremated by the artist. The ashes were then placed in an ‘intelligent’ urn – a biodegradable urn with the seed of a tree inside. A QR code allowing one to connect with the Instagram account of the deceased together with the dates determining the period of his online existence were then printed on the surface. In this work Krzymowski brings together two opposing elements – the popularity of the network with the sacredness of the funeral. The work invites us to rethink the transience of human life in the context of the flow of virtual information.

Piotr Krzymowski, “Swombies”, Homo cellularis exhibition, Toruń, 2019, photo by Dawid Paweł Lewandowski

The exhibition concludes with the series of post-apocalyptic sculptures entitled Swombies – transparent glass models of human heads filled with elements of self-destroying technology. In 2012, the neologism swombie was voted the youths’ word of the year in Germany, and arose from the combination of the words zombie and smartphone. It refers to pedestrians who walk slowly, focussing solely on the screens of mobile phones without paying any attention to their surroundings. Since it’s proven such a safety risk, cities such as Chongqing and Antwerp have introduced special lanes for smartphone users in order to ensure both their safety and that of drivers. People who lose themselves in the web seem to forget about the real world around them. The internet is also becoming the place to escape from the problems that surround us, whilst somewhat paradoxically a place of enormous violence, hatred and crime. Many of those surveyed state that they encounter far more severe hate online than they ever have in real life. Krzymowski’s Swombies are a picture of what will remain from human civilization if the phenomenon continues to grow. Global warming is no longer merely a possibility, as many would like to think, but a real problem that may result in tragedy. Droughts and hunger, rising prices and reduced quality of life are for many an unfortunate reality. Krzymowski creates works that warn of the side effects of technology and foresee the apocalyptic future.

When Alexa met Google Home and Siri, video installation, Homo cellularis exhibition, Toruń, 2019, photo by Dawid Paweł Lewandowski

This exhibition at the CoCA in Toruń is a reflection of the modern world. Less attention is being paid to nature whilst forevermore is devoted to a virtual reality. Krzymowski attentively and subtlety analyses the modern world that surrounds us. Some conclusions may seem humorous, while others could be catastrophic. As the world continues to speed up, will we manage to ever stop?

Written by Mateusz Kozieradzki

Piotr Krzymowski. Homo cellularis

The exhibition is open until 5 January 2020.

Curated by Mateusz Kozieradzki

Piotr Krzymowski, “Swombies”, Homo cellularis exhibition, Toruń, 2019, photo by Dawid Paweł Lewandowski

Piotr Krzymowski, @paulomacareno, bio-urn with cremated photographs published by @paulomacareno, 15 x 50 cm, 2019, Homo cellularis exhibition, Toruń, 2019, photo by Dawid Paweł Lewandowski

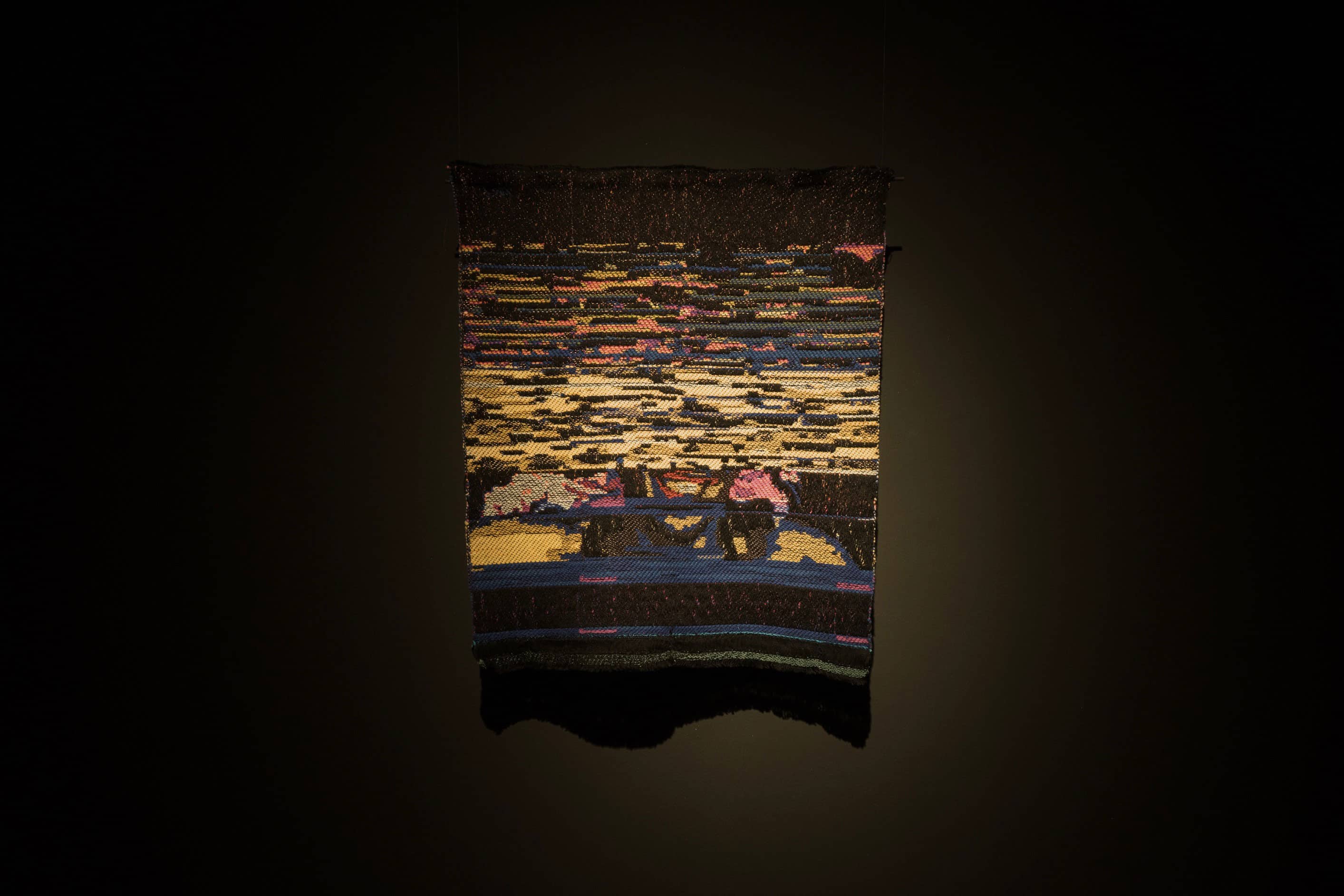

staying in touch, Skype glitch, jacquard, 70 x 80 cm, 2016, Homo cellularis exhibition, Toruń, 2019, photo by Dawid Paweł Lewandowski