2015 is the Year of Tadeusz Kantor nationally and abroad and the great works of the wholly interdisciplinary artist and master of theatre have come as far as Edinburgh, taking part in the Fringe Festival’s Summerhall exhibition Inbetween Structures. Maja Lorkowska talks to curator Marc Glöde about Kantor’s unanswered questions, fascination with processes and painting on broken glass.

Marc Glöde, curator of the exhibition ‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

Maja Lorkowska: How has the idea for the show come about initially – was the discovery of the film the main factor in instigating the exhibition?

Marc Glöde : It started last year, when I was doing a show in cooperation with the Polish Institute on experimental film from Poland. After working together we were thinking about what we could do as the next step, what we wanted to focus on. They asked if I had any suggestions if a show was to happen in 2015, so I said: yes, I would be very interested in doing something on the occasion of Tadeusz Kantor’s 100th birthday! They were excited about that, but decided that it is quite a broad, general topic and a lot of shows will be coming up this year. I mentioned that I would specifically be interested in the recently rediscovered film Attention… Painting! that was made by Kantor in 1957. When I was in Krakow doing some research at the Cricoteka, it was the first time that I saw this film. I had been reading a lot, noticing references to it, but no one had seen it since, probably, the beginning of the ’70s. I was really excited for the chance to see it, it was really quite astonishing in a lot of ways. My idea was to take that as a kind of starting point, or to make the film the heart of the exhibition in Edinburgh and Berlin.

ML: Keeping in mind the fact that Kantor’s key international début took place in Edinburgh during the festival in 1972, was it important that the exhibition was also in the context of the city, coming back full circle?

M.G: At first we did start to talk about the exhibition for the Berlin context, the Polish Institute in London was very happy to hear about it. But since I knew very well about the connection between Kantor and Edinburgh, they suggested that maybe it would be a good idea to place the show in the UK and bring it back to the city as well, as there has been this strong link historically with Kantor’s work from the ’70s onwards. It was very interesting for me to talk to Richard Demarco, who in 1972 brought Kantor to Edinburgh for the first time and from that moment on, he came back, I think six times, doing performance work but also teaching together with Joseph Beuys. This strong affiliation with the city and its space made it very natural for me to say: ‘Yes, let’s do it in this context’, and the Fringe Festival were, of course, also very excited when they heard about the chance to do the show. A show that might not be so much from the side of Kantor that you already expect to see but one offering some new perspectives of him and has work. These might be known in the Polish context because he is one of the national icons in the arts, not only in theatre but also in other disciplines. Yet specifically the question of film, drawing and collage is not so well known outside of Poland. For me, it was a chance to take a look at this earlier period of Kantor’s oeuvre and use that as a perspective which opened up a new side for people that know Kantor, maybe from their experience in the 70s, being theatre buffs, or just reading about it. So to have that, and to add this dimension of dealing with different forms of art was very important to me, and it was very exciting to have a chance to go deeper into archival research, take it from there and open up a new dimension for myself as well.

Marc Glöde and Richard Demarco, ‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

ML: That’s actually one of my next questions too – of course we know that he’s very well known for his theatre productions, especially the later ones like The Dead Class, so given this new context, what would you like the audience to take away from the exhibition?

MG: You see clearly how the different aspects of Kantor’s practice are linked, and that is something that you begin to understand if you go back from the ’70s and dig deeper into the ‘40s, ‘50s, ‘60s, and see how he was interested in the same question: it is always something that he was busy with, the kind of ‘processuality’; what are the processes of making art, how can one raise new questions, how can one be more open and not too clichéd about one’s own perspective as an artist?

What was so important for me, was to understand that, Kantor was moving inbetween these different forms, which is also why we headed towards the title of Inbetween Structures. What we understood was that he was very precisely choosing the forms that he was working with. But very contrary to what you see, for instance, in the West at the same time classical, traditionally educated painters that start to work with photography and immediately after that experience turn back to being painters. Kantor was really experimenting with how mediums such as collage, film, photography, performance, theatre, all these different forms and structures that come along with them, could combine. The question, the challenge was that of ‘how can I produce something that keeps me thinking, challenging myself, thinking about my own ways of perceiving, observing, watching how an art form develops while I’m going through a museum’ for instance. This is something that was an ongoing topic in different forms, and that is also a topic for him in the theatre. And it is not so much of a surprise that he began to head more and more into the theatre, into the ‘nowness’ of the medium, the actuality of it, and in a certain way I think that is where he got what he was more interested in and why he was tending towards that medium more and more.

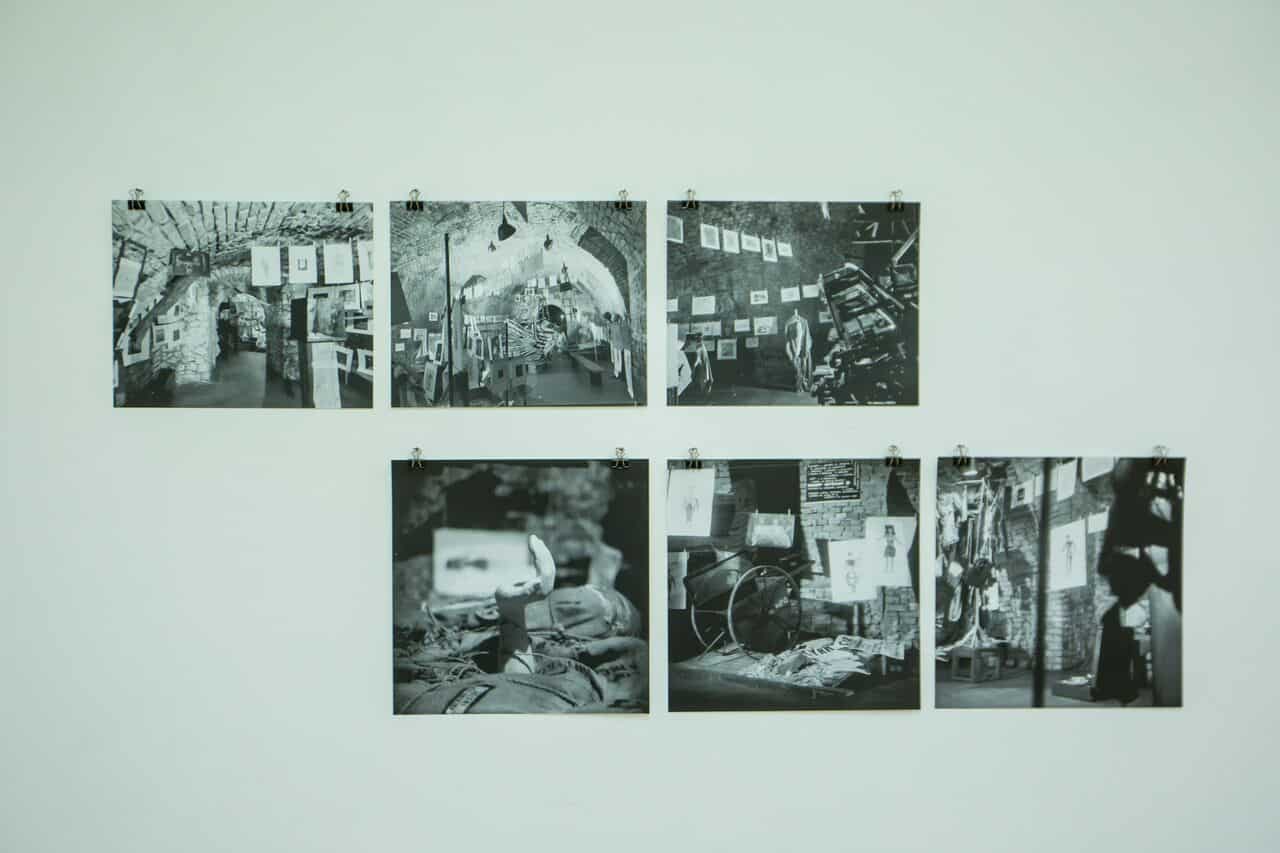

‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

ML: Would you say then, that it was a lot more about the process than the actual final result, seeing the finished object?

MG.: Exactly. It’s not about the finished object, it’s about keeping it alive, not meeting your expectations, it is not about getting too laid back: ‘Oh, I know so much about painting.’ Yes, well, good for you, it just means you’re not open any more. You have certain clichés in your head and start to not really watch what’s actually in front of you. Kantor was really interested in the ways he could irritate the observer, getting them out of the routine of walking through a museum. Not only for the audience, the question, the challenge was the same for himself – how one can surprise himself as an artist in his way of producing an artwork. It was a very strong dynamic, which became very clear for me also, when I saw the film for the first time. You can see certain echoes or resonance that trace it back Hans Namuh and Jackson Pollock. Namuh is making a film about objects and Pollock, but you see Pollock is painting, the canvas laying on the ground, painting on glass being shot from below – you can identify strong echoes of what Kantor is doing in his experimental film. But then, it was never about him at that point. It is especially interesting when you know his theatre work, his importance as the activator on stage, making it is almost impossible to imagine his works without him there, on stage. Here, in the film it was the complete opposite, it is not about him at all. While Namuh was shooting Pollock in the method of staging a persona, Kantor was not interested in that. He cooperated with two young film students from the Łódź Academy who just graduated in film, so he was very much interested in how does a painting come together, how to show what actually happens when you pour paint on canvas, how does it dissolve or smear. But you never see a hand or the person doing it. It has a certain kind of theatricality that is in the painting, the painting itself becoming the main protagonist.

ML: It’s fascinating actually seeing the film, because it’s really quite confusing not knowing where all the action is coming from, paint is being poured from all over and all the colours constantly changing!

MG: When you see that in combination with Pollock, there is a certain aestheticism which Namuh is trying to keep intact, while as you mentioned with the Kantor film, it is very different. At one point they throw a stone at the glass which they’re painting on shattering it into tiny pieces, and the colours start to blend into one another, getting to a grey, brownish smear – not something that you could call a nice colour! It’s not about thinking that this looks beautiful, but it is a process, breaking the glass we break the illusion of seeing the painting in the making because you also see the destruction of the machinery that is actually constructing the image.

‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

ML: It does say a lot about translating the medium of painting into film, as it is not an easy thing to achieve. Like you say, you can do it the Pollock way in which he is the star of the recording, or the Kantor way…

MG: That’s why it was important for me to include a lot of the technical drawings that he was producing alongside, sometimes reworking them later to get more explicit about how the film was made. There is also a drawing dimension to it, film drawings which are more technical, storyboard-style almost, and combining them with drawings that he did in the context of Informel painting and how they overlap – it is not a pure technical drawing that he’s doing there, certain aesthetics come along with this. It is not only to show the staging of the film set but exposing the dynamic of the colours exploding on screen, and capturing this not only with the film camera, but attempting do the same with a pencil. That’s why we say ‘inbetween structures’, he is thinking about this through the drawing, but also through the film camera to completely different outcomes.

ML: The rest of the pieces in the exhibition other than the film and drawings: some of the photographs, the larger paintings – how do they relate to the film?

MG.: I have put in some drawings which Kantor referred to as ‘Tachism’, we were fortunate enough to use them from the Lech Stangret, Warsaw collection. The funny thing is with these pieces, that when looking at them you almost cannot decide if you’re looking at a Rorschach drawing used in psychology, where they resonate as purely abstract images. At the same time you stand in front of them and wonder what you are actually looking at, is it a drawing, is it a Polaroid that has been taken out of the camera too quickly? Somehow, they are inbetween and we are not able to decide exactly what form it is. And when you get very close, you see that they are in fact ink drawings – Kantor used ink and let it flow over the surface of the paper, creating strange landscape-like images. I was very interested in how the use of ink was leading the viewer to confusion over what one is looking at.

Other work that he included, which I found really important from my position as curator, are works that are connected with the so called Anti-Exhibition of 1963 because I had the feeling that the whole situation, all the questions that Kantor was dealing with, somehow came together in this show. The location of it was very carefully decided, as well as all that was to be combined: the kind of different objects, drawings, including collage and importantly, the manifesto. This manifesto specifically says he is not interested in the finished object, he is interested in ‘processuality’, not letting an art object end in the museum at which point it would be dead. It is all about activating the thinking process, producing something new. He not only used the manifesto, but also took images from the exhibition, made copies of them later, made a collage – so after the production of the exhibition the whole process was not yet finished. Kantor had an idea of how to capture the atmosphere of this exhibition, he had six photographs and later produced a collage of those combined six images, together with the text, highlighting certain parts of the text that show what he is actually interested in. So it never stops. It was funny for me to talk with Richard Demarco who said: ‘Well, you know Kantor is not dead!’ So his work is continuing, and that for me is one of the main things that I wanted to bring to Edinburgh, to the Fringe Festival – if you think you know so much about Kantor, let’s looks at another side of his work, focus on some new questions, maybe also questions that are important at this very moment. Some people were questioning the show in the context of the Fringe which is so theatre-focused, to which I said that if you look at contemporary art at the moment there is a huge interest in performance, re-enactment, you name it, and why is that? To a certain extent, it has something to do with everything being very much available at this moment, everything is there, randomly accessible, and people are aware of a kind of revalidation process, nothing has a value any more and people are urging to be faced with some kind of authenticity, uniqueness. This ‘nowness’, being able to focus on that and to see that it is actually included in a lot of Kantor’s work from the early phase onward, might be a surprise for a lot of people.

‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

ML: What can you say about the ways in which Kantor has cooperated with artists in the past and continues to influence them today?

MG: I can see that as a parallel development, that kind of interest in newness and I am assuming there is a certain interest in Kantor’s work generally, and theatricality per se, at this moment. The question of cooperation – it was always key for him, to a certain extent to cooperate with different fields. He taught with Joseph Beuys and cooperated with him in Edinburgh, if you know of the ideas of Beuys, his ‘social plastic’, leading to the famous quote that “everyone is an artist”, it challenges and leads to the moment where this art experience and development collides with everyday experience, which continues to be present in Kantor’s work. In a way, he is following a trail that was established by Marcel Duchamp and the readymade, the idea of the objet trouve, although Kantor used another terminology of ‘the everyday object – the object of a lower rank’, so the thing that you really find everywhere. This challenges your understanding, the moment when something shifts from being a thing that is usually thrown away or not even seen, and through a certain process we can begin to see this object, which is usually taken for granted, or unappreciated. I think these are things that one the one hand had historical resonance points, like Duchamp, and working with the emballage’ but then trying to foster and engage artists, like Beuys. In fact, he may have been an amazing artist and teacher, but eventually at one point steps out of this context and becomes one of the founders of the Green Party in Germany – which is something to consider.

ML: I guess that’s as interdisciplinary as you can get! Coming back to the show, the Inbetween Structures exhibition is later heading to Berlin (opening on the 10th of September). Do you think the reception there will be any different?

MG: Yes, it will be. It comes from the fact that we will have a completely different spatial situation. It will be more condensed. We had a very luxurious situation in Edinburgh, so that gave us a lot of space for each work. It will be very different in Berlin, maybe more Kantor-style!

ML: So lastly, what is your personal favourite aspect of Tadeusz Kantor’s work? I personally like the volatility of his character and the extremes of emotion which he put into working with actors. What would you say you cherish the most about his work and persona?

MG: What I really appreciate is his openness, and how he was capable of keeping certain questions alive. Sometimes I use the word ‘irritation’, that’s how you know you’re seeing great art. There is sometimes this moment where it gets boring: there is a question which is getting answered and then there are other artworks which keep asking and challenging you, almost like a mosquito bite. It just doesn’t ever stop, it keeps asking what you think about this, or that. And trying to answer that keeps you going and looking for a new perspective. This for me, in the work of Kantor, is just amazing, and that’s why we chose to go ‘inbetween structures’ for the show.

5 August – 4 September 2015, Summerhall, Edinburgh, part of Edinburgh Festival Fringe

10 September – 15 November 2015, Polish Institute Berlin, part of Berlin Art Week

The project has been initiated by the Polish Institute Berlin and is co-produced by the Polish Cultural Institute in London in partnership with Cricoteka, National Museum in Krakow, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and Krakow Festival Office and Culture.pl.

left: Marc Glöde and Richard Demarco, ‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

left: Karolina Kolodziej, Marc Glöde, Anna Godlewska, Anna Gruszka, preview of the exhibition ‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015

‘Tadeusz Kantor: Inbetween Structures’, Summerhall, Edinburgh, photo ⓒChris Scott, courtesy of Polish Cultural Institute in London, 2015