Art and cinema rely on visuality, though they approach it from different angles. By definition, the film seems like a natural extension of painting, an image set in motion. However, in this case, aesthetic is deemed secondary to narrative. According to popular opinion, storytelling takes precedence over the visual quality of a film. Mainstream features notwithstanding, the medium can undoubtedly serve a multifaceted art practice. Since the birth of cinema, artists have always gravitated towards the medium, seeking to create a brand-new quality by combining the image with motion and later sound. This sort of investigation usually gives rise to some experimental niche productions. There are exceptions to the rule. An artist may branch out into cinema, imbue the medium with their unique visual sensibility, ultimately rise to stardom and come to direct mainstream yet compelling, ingenious and fresh films. The epitome of an artist turned filmmaker is Steve McQueen, the Turner Prize laureate (1999) and three-time Oscar winner for 12 Years a Slave (2013) – a poignant tale about slavery whose language was influenced slightly by video art aesthetic. Another example would be Norman Leto, formerly a self-taught painter, currently a prominent multimedia artist who burst onto the Polish art scene with his film Photon (2017). This box-office smash hit, a surprisingly accessible amalgamation of science documentary and eccentric arthouse film, was embraced by a wider audience, not just hardcore art aficionados.

An increasing amount of contemporary artists decide to become filmmakers. In the history of cinema, there have been a number of highly successful directors who in fact, had specialised in painting. Allow me to introduce to you some of those figures and consider how an artistic background affected their filmography. Since Contemporary Lynx situates itself on the verge of the Polish and Western art world, our selection consists of two artists from Poland, America and the UK.

Here are the masters:

Andrzej Wajda, Wikimedia Commons

Andrzej Wajda (1926 – 2016)

This legendary Polish director never managed to gain international recognition, as opposed to Roman Polański and Krzysztof Kieślowski. A highly influential auteur, the filmmakers’ filmmaker was appreciated by masters such as Akira Kurosawa and Martin Scorsese, the latter of whom has mentioned on more than one occasion that he learned the language of cinema from Ashes and Diamonds (Popiół i Diament, 1958). At some point in his life, Wajda dropped out of the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. As a painting student, he came across Andrzej Wróblewski, one of the seminal Polish painters of the 20th century. This encounter prompted a critical re-evaluation of his abilities and the ultimate decision to become a filmmaker rather than a painter. Wajda often referenced the painterly practice of the artist he personally revered, in films like the deeply intimate Everything for Sale (Wszystko na sprzedaż, 1969) and his documentary swan song titled Wróblewski According to Wajda (Wróblewski według Wajdy, 2015). Through approaching images artistically, Wajda introduced the language of visual metaphors into Polish cinemas. The so-called Polish Film School wouldn’t have been acknowledged internationally if it wasn’t for Andrzej Wajda. Additionally, his films made frequent allusions to the famous paintings, such as The Birch Wood (Brzezina, 1970) by Jacek Malczewski and Sweet Rush (Tatarak, 2009) by Edward Hopper.

Andrzej Wajda, Sweet Rush (2009), Press Materials

Peter Greenaway, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Greenaway (born 1942)

The Welsh filmmaker, who graduated from the Walthamstow College of Art, trained initially as a muralist. One of the greatest eccentrics in the history of British cinema, he reached his peak popularity in the 1980s and 1990s. Inspired by the art of painting, Greenaway pushes the boundaries of cinema; defies its stale conventions with the view of expanding and disrupting its visual language. For the audience, his films are elaborate games based on a series of references and cultural tropes. Greenaway’s signature style is marked with his obsessive adoration of Baroque painting (Vermeer, Velázquez, Rembrandt etc.). His main protagonists, tortured artists facing creative and moral dilemmas, can be purely fictitious (e.g. the eponymous draughtsman in The Draughtsman’s Contract, 1982), inspired by real-life or literary characters (e.g. Prospero in Prospero’s Books, 1991). Nightwatching (2007) features Rembrandt himself entangled in a fictional yet quite subversive and sophisticated plot concerning the creation of one of his most famous paintings, namely The Night Watch. Working across traditional and experimental visual discourses, Greenway fills his motion pictures with the form and content representative of painting.

Peter Greenaway Nighwatching (2007), Press materials

Derek Jarman, Wikimedia Commons

Derek Jarman(1942 – 1994)

An iconic figure in British queer cinema, the iconoclastic visionary director with an undeniable talent and broad horizons explored similar themes to Greenaway, his colleague, and to some degree a rival (since they both adapted Shakespeare’s The Tempest). However, there are some fundamental differences between these filmmakers. While Greenaway seems elitist, Jarman considers himself a “people’s director” on the side of mavericks and nonconformist rebels. His first solo shows staged after his graduation from Slade School of Fine Art opened to rave reviews. The artist himself was soon hailed as the most promising painter of his generation. Though he never abandoned painting completely, Jarman discovered that the canvas fell short of his expectations and therefore branched out into stage design and finally filmmaking, which he ended up focusing on. Due to his deep underground roots, merely two of his films entered the mainstream: a rebellious Jubilee (1977) and an unusual biopic Caravaggio (1986), which portrays the masterful painter as a director of sorts, a set designer who lives and breathes art.

Meanwhile, Jarman adopts the role of a painter who emulates Caravaggio’s style in his frame composition. It’s a deeply personal film. Jarman identifies with the character, shares some of his traits, adds a touch of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s biography and as a result, manages to create the archetype of the outsider artist. Another film by Jarman worth seeing is Blue (1993) – a freewheeling, intimate and poetic account of sickness (Jarman died of AIDS), basked in the blue static imagery that pays homage to Yves Klein.

Derek Jarman, Caravaggio (1986), source: BFI – British Film Institute

David Lynch, source: BFI – British Film Institute

David Lynch(born 1946)

Not only did the American director study painting, but it might actually be this very art medium that holds the key to deciphering his obscure and eerie filmography. One’s perception of the world which is visual rather than purely linguistic usually indicates a person’s vivid imagination, which keeps running wild, making odd connections between things. Lynch’s defiance of linear narrative can be observed already in his short film The Alphabet (1968), which is now regarded as his manifesto. His gradual transition from painting into filmmaking transpired through animation. Lynch’s debut film Sick Men Getting Sick (1967), a painterly image on a several minutes loop, brings to mind a piece of video art rather than cinema. The director of Mulholland Drive (2001) draws on three separate art movements of the 20 th century, the phantasmagorical quality of surrealism imbibed with the expressionist aesthetic being the obvious one since it permeates all of his films. As a young artist, Lynch developed a deep fascination with Oskar Kokoschka. He tried and failed to become his apprentice, going to great lengths by travelling to Salzburg to apply. Last but not least, pop-art spawned his ironic and subversive take on the icons of American pop culture, which he tapped into in Blue Velvet (1986) and Twin Peaks (1990-2017).

David Lynch, ‘I Fight with Myself’, painting, source: widewalls

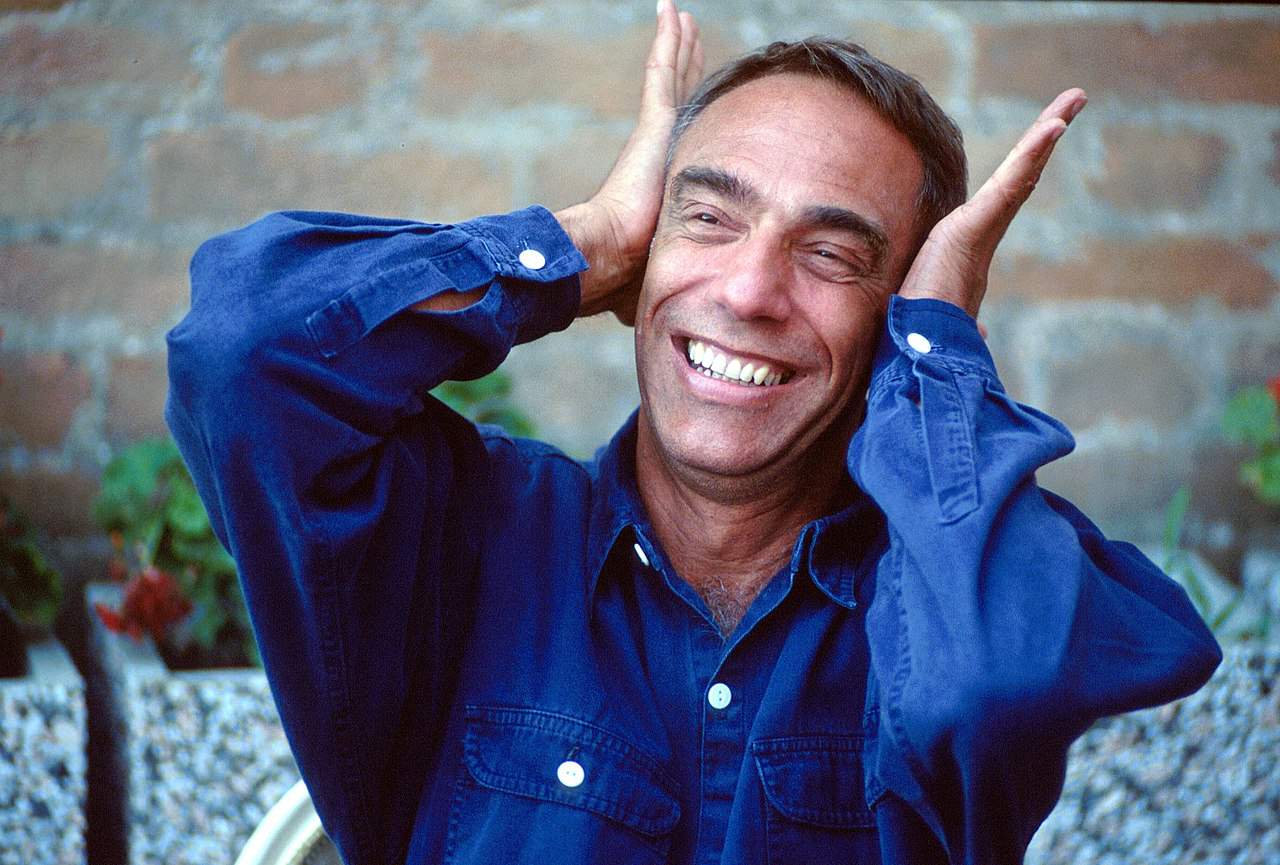

Julian Schnabel, source: Getty Images

Julian Schnabel (born 1951)

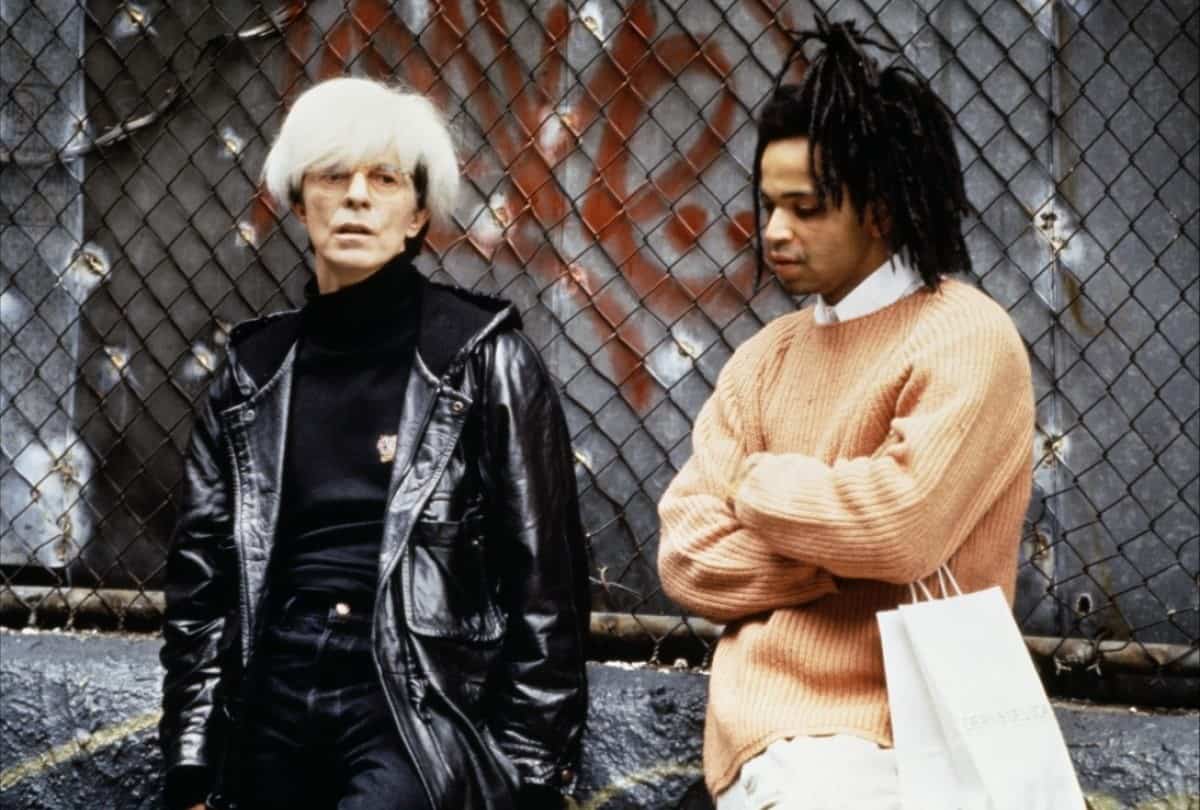

Schnabel has received the highest acclaim for his work as an artist compared to the rest of the filmmakers discussed in this article. As a seminal figure of the 1980s art scene, he created a series of neo-expressionist large-scale paintings with an edge of brutal expressivity, one of which was used for the cover of Red Hot Chili Peppers’ 2002 album By the Way. His works belong to the most prestigious collections of contemporary art in the world. It wasn’t until the 1990s that he directed his first feature film about the life of Jean-Michael Basquiat – his fellow New Yorker, rebellious artist and Andy Warhol’s apprentice. Despite its peculiar nostalgic undertones and quite conventional execution, Basquiat (1996) is now associated mainly with David Bowie’s portrayal of Andy Warhol. Schnabel kept working and honing his directorial skills. In 2007, he made the excellent The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. A first-person narrative of the film unfolds from the perspective of Jean-Dominique Bauby, a fashion editor who communicates with the world only with the blink of an eye due to severe paralysis. Sublime visuals (captured by the Polish cinematographer Janusz Kamiński) and ingenious storytelling earned Schnabel international recognition among professional filmmakers. The director has always been captivated by the life stories of other artists, in particular, painters. At Eternity’s Gate (2018), his recent biography of Van Gogh was well-received at the Venice Film Festival. The critics praised his original approach to the subject that avoided the genre clichés.

Julian Schnabel, ‘Basquiat’ (1996), source: Miramax

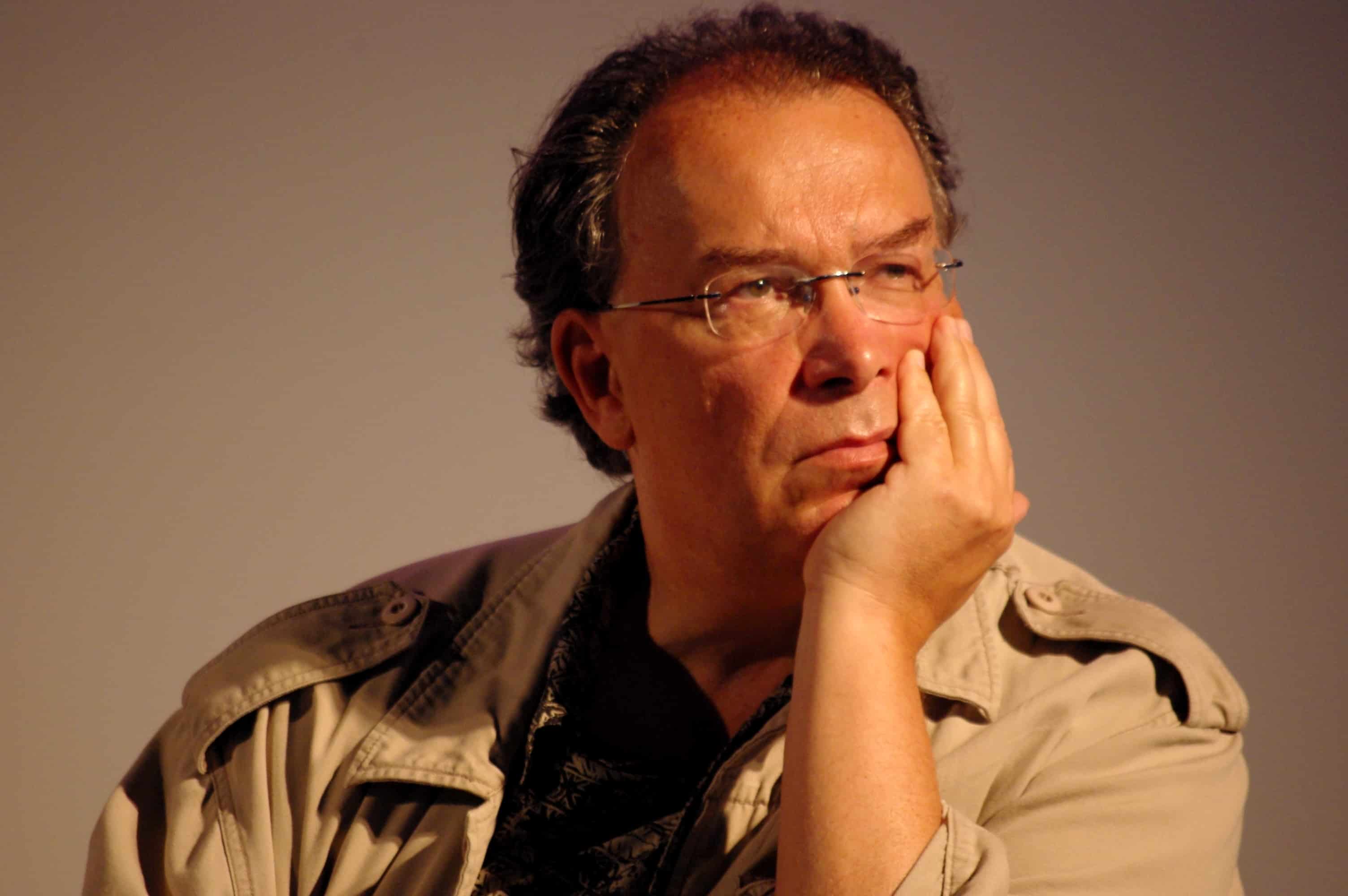

Lech Majewski, source: Filmweb

Lech Majewski (born 1953)

Last on the list is another Polish artist, whose works are more recognisable abroad than in his own country. He is a screenwriter and the producer of Basquiat, directed by Schnabel. In spite of his college film education, Majewski had developed a remarkable affinity with the art world owing to his uncle who worked as an art dealer in Venice. Apart from painting, Majewski makes sculptures and video installations, always in limbo, somewhere between art and cinema, Poland and the rest of the world. For years Majewski has been dismissed by the Polish film community, which he has never quite fit into. His practice was finally held in high esteem by the international art world, which leads to his retrospective at MoMA (2006), followed by his long overdue solo exhibition at the National Museum in Krakow (2011). Majewski tends to stir up controversies due to his aversion towards modern culture, which he articulates freely.

Nevertheless, the juxtaposition of his backwards-looking worldview or conservative (religious, ethical and artistic) values he cherishes against an innovative approach to new media art and other contemporary forms of expression makes him one of the most original, mature and fascinating artists of his generation, who escapes pigeonholes.

Similarly to Greenaway, Jarman and Schnabel, Majewski is most intrigued by other artists and their creative process. His films inspired by classical European paintings are particularly worth mentioning here: The Garden of Earthly Delights (2004) drawing on Bosh’s masterpiece, as well as The Mill and the Cross (2011), the international film production that brings to life and examines closely The Procession to Calvary by Peter Bruegel the Elder played by Rutger Hauer. Just like in the case of Caravaggio by Jarman or Nightwatching by Greenaway, Majewski decides to turn the tables on the audience and accept the role of a painter, while his character shapes and turns reality into art, directing the story of his life. Most of the abovementioned artists draw parallels between painting and filmmaking. It can’t be a coincidence. As it turns out, these two disciplines have much more in common than it might seem.

Lech Majewski, ‘The Mill and the Cross’ (2011), Press materials

Written by Karol Szafraniec

Translated by Karolina Jasińska

Edited by Maggie Kuzan