Rute Merk (b. 1991) is a Lithuanian painter currently living and working in Berlin. In 2020, her personal exhibitions were held in New York (the Downs & Ross gallery) and Shanghai (the Vacancy gallery), and a cycle of paintings was created in collaboration with fashion houses in Balenciaga (published in the journal Mousse Magazine). But I don’t want to tell you about Rute because of her international CV. The path chosen by the artist is intriguing and can become a long and interesting journey around the digital world, where this Y-generation representative feels natural. To capture the souls of virtual characters, she uses old technologies – a brush and oil paint.

Born in the small Lithuanian town of Raseiniai, Rute purposefully chose painting studies at the Vilnius Academy of Arts. She did not fit in the local field of painting, one of the teachers even stated that “she is not fit for painting”. Instead of trying to reconcile and adapt, Rute sought creative action and inspiration in the circles of conceptual art. She did not stop painting. It is interesting to look at two paintings, “David” and “Greta (Aki Ross)” created in Vilnius (both in 2015).

“David” depicts a bronze sculpture of David by the Florentine artist Andrea del Verrocchio (1435-1488). In retrospect, it points to a turn toward contemporary themes of the artist. Firstly, there is the popular version that the model of David was Leonardo da Vinci, a young beauty who was studying with Verrocchio at the time. Upon learning this, we instantly stop thinking about a king of Israel so distant from us today and in the image begin to look for a Renaissance genius that we all seem to know. However, very little is known about him, his biography is shrouded in guesswork and legends, in other words, fiction. Secondly, there’s the sculpture itself: David’s smile is framed by light curls, the body is slender and somewhat girly, the pose is reminiscent of one of today’s mannequins, his beautiful clothes (oh, when will men finally start wearing skirts more often, they suit them so much!). Rute’s David is only portrayed up to his graceful thighs, and the head of the defeated giant Goliath is hidden. If it weren’t for the name, it would be challenging for the viewer to decide which gender character is depicted. The artist’s David is attractive and androgynous. He’s our own because he is human. And he is alien because his gender, mood, and history are unreadable.

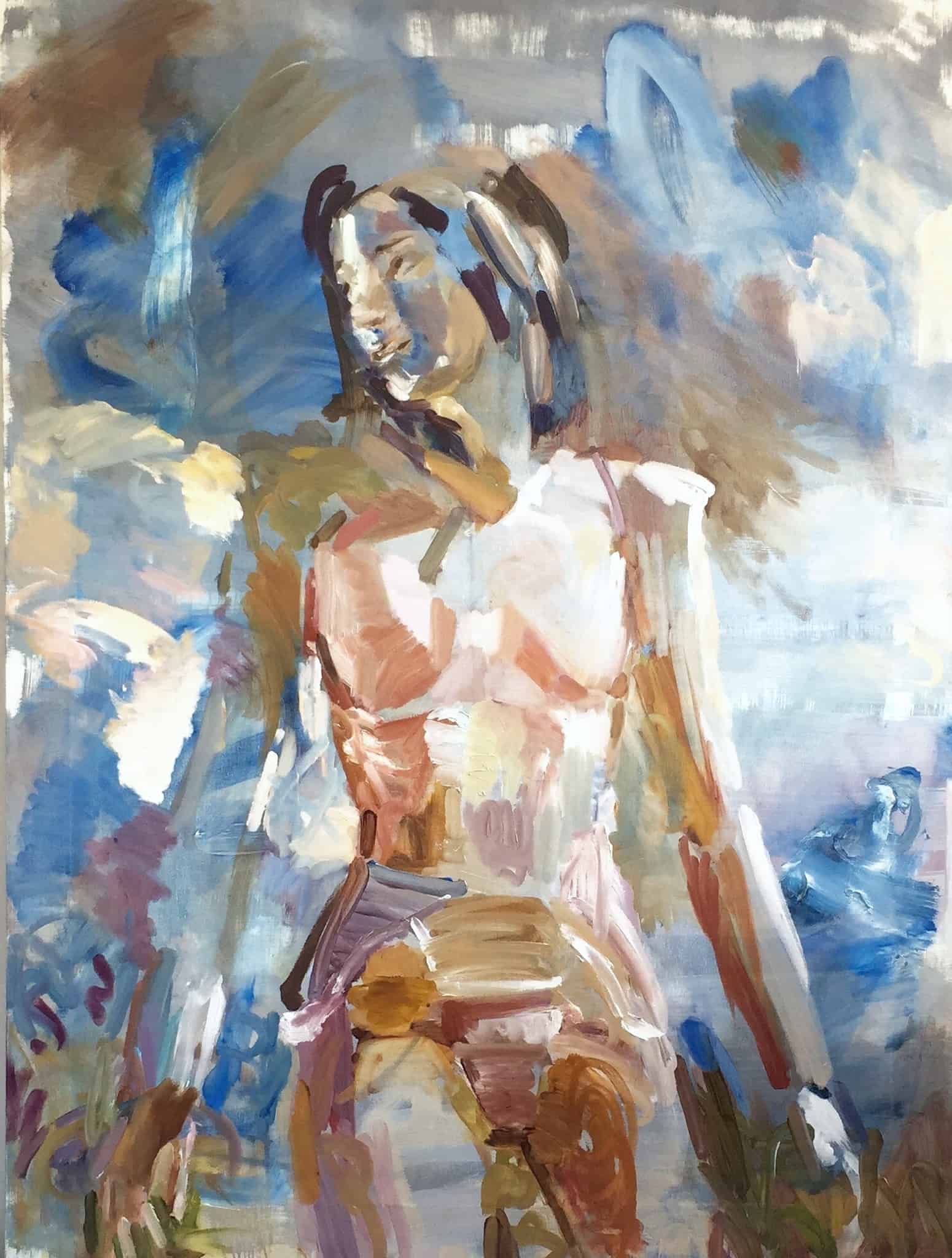

The painting “Greta (Aki Ross)” is quite similar. The figure, painted in sensitive expressionist strokes, also has no accentuated gender features. This time the name suggests that it is a woman, but she is free and strong, with a fighter’s posture. And yet – she is not human! Aki Ross is the heroine of Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001), one of the first virtual (photorealistic computer-generated) actors. So, again, it’s kind of a conventional portrait, but we look at fiction, not at a body. It’s intriguing. Nothing creates intrigue like tension. Tension is created by conflict. The more subtle that conflict is, the more time the viewer spends in front of the image trying to understand it. Rute’s paintings are disturbing because of the problem of a recognizable but unfamiliar image. After going to study painting in Munich, she added to the intrigue of her paintings using painting techniques.

Greta(Aki Ross), 2015, oil on canvas, 131 x 101cm

Is it necessary to recognize the character?

It’s interesting to compare portraits of Aki Ross in 2015 and 2018. The character and the composition are the same, but the plasticity changed significantly. “Studies in Munich led to the development of plastic language, in part because of a more active, abundant flow associated with painting. I saw a lot of new exhibitions, new (and old) paintings “live” in Munich and Berlin, starting with Gerhard Richter, Miriam Cahn, Florian Süssmayri, Avery Singer, Austin Lee, and ending with Rembrandt or Bruegel,” says Rute. After finally finding a unique language and theme, for the past couple of years, she has been creating a 21st-century portrait gallery, in which images of the digital world, captured by the “dinosaur” method of oil paint on canvas, tell a tacit story about today’s life.

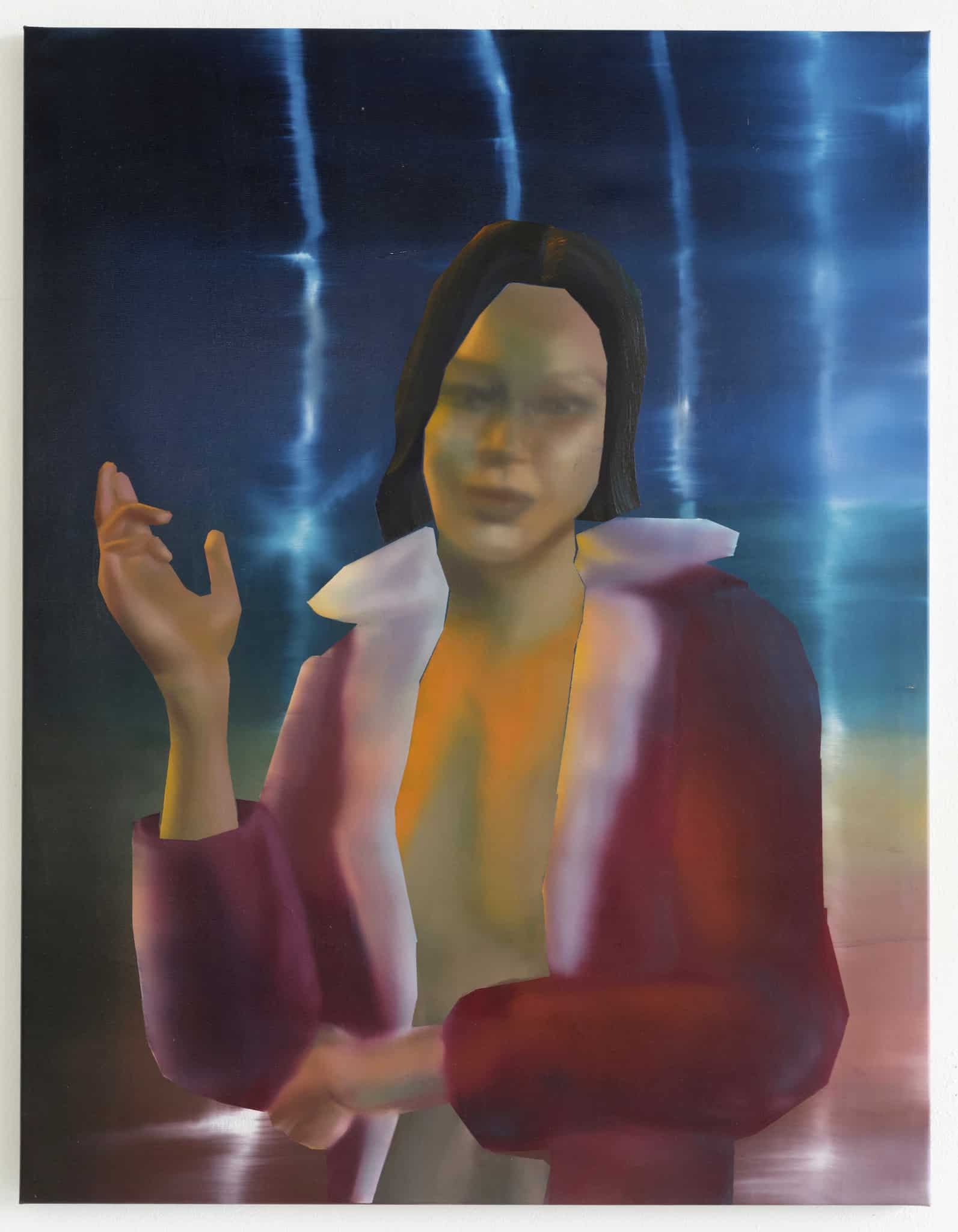

As one of the inspirations of these portraits, the painter mentions the portrait genre “tronie” prevalent in Dutch and Flemish painting in the 16th and 17th centuries (in the Dutch language of the time, this word meant “face”). They are portrait studies that depict people with unusual facial expressions or in interesting costumes. Unlike traditional representational portraits, these are not specially ordered, the depicted person remains anonymous. It can be an old man or a child, an embodiment of pure beauty or a drunkard, a person grimacing or having naturally strange features – something that caught the artist’s eye. Some of the most famous “tronies” are Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring or Frans Hals’ Witch of Haarlem or Malle Babbe. However, thinking about the paintings of Rute Merk, I remembered the old portraits of 16th-17th-century GDL rulers and noblemen. Men and women are depicted in static poses, full-height, or half-height. They do not look “alive”: their expressions and postures do not have a distinct individuality, their bodies are indiscernibly hidden under costumes. We know almost nothing about some of them besides their name and title. They are a bit funny, but we still look at them gently, like some distant relatives never seen before – after all, they’re ours. Computer game or movie characters depicted in Rute’s paintings are somewhat similar: they are strange, they always look calm, or even indifferent, their bodies are also hidden under textiles. We know almost nothing about them, but they are our own. Only the nobles in the old paintings live in history, and the characters of Rute’s paintings live in virtual space. Both find room in our thoughts and sometimes in our hearts. We will never meet, but they are a part of our lives.

Hungry for more?

Is a painted 17th-century nobleman unknown to us more real than a painted computer-generated movie character Dr Aki Ross, Michael Jackson’s superhero character from Do You Remember the Time or Lilu (Leeloo) from Fifth Element? Factually, yes – such a person once really existed – but the feelings and emotional connection to those virtual characters would say otherwise, if there’d ben a contact with them, of course. I am sure that to some readers of this text, the names or stories of Aki Ross, Lilu, and other Rute’s characters do not mean anything. Just like to some younger people today, the names and iconography of mythological or biblical characters in ancient paintings mean nothing. As I thought about it, I asked Rute if the viewer was supposed to recognize the characters she portrayed. “There isn’t one right way to see. After all, while painting, I also interpreted the information, material, and motive. Seeing is an intellectual activity, we all see differently. Of course, I would like the viewer to be able to see the way I saw it. But the most interesting thing for me is when the viewer sees something more than I did. This happens very often and shows not how interesting the works are, but the people,” replied Rute. She understands the problem of recognizing characters of figurative art and chooses to portray what she herself discovers an emotional connection with. A moment of fascination is important to her. On the other hand, a painting is always more important than what it depicts, and the artist’s plastic solutions contribute to that.

Painting the virtual soul

Today, images (including works of art) are increasingly spreading digitally. We look at, evaluate, and buy works on Instagram and other platforms. This sometimes determines the artists’ plastic decisions – works are created keeping in mind how striking the result will appear on a screen, which doesn’t convey the scale, the layers or shades of the painting. Still, Rute Merk’s paintings are more beautiful when viewed “live”. Again, because of the tension.

At first, it may seem that the particularly smooth painterly surfaces of the paintings are created by spraying paint. Besides, when you look at the painting in close proximity, you get the impression that its individual parts are precisely cut out and glued onto the canvas. The portrait seems to be made up of different fragments: face, hair, and costume details are as if taken from somewhere and placed on top of each other just like by copy-pasting. The artist patiently uses brush and oil paints to create what is constantly done by a modern person: she sticks fragmented lines of information she receives on top of each other, adjusts digital images and, of course, molds her identity on social networks from selected pieces (although looking at some stories on Instagram, it seems that for some the boundaries between social virtual and private personal space are no longer there). The fragmented nature of images, information, and thinking is our way of life. And this is where Rute turns in an unexpected direction, which is why her work is so interesting. She does not investigate or criticize the fragmented reality of today. She looks for traces of reality in digital images. She tries to show that it is not banal but real. Perhaps even, as the artist herself poetically puts it, she tries to find the soul of a virtual image.

Contemporary Lynx presents to you five noteworthy Lithuanian artists, whose art is striking, even amongst the melancholic and magical atmospheres present in Lithuania, Heart of the Baltics.

The screen has become both a place of entertainment and work. We are often ceaselessly networked and social, but also separated and alienated at the same time.

I agree that most of my characters have a strange calm or indifference. Mom says they are often as if not in the mood. I am interested in the deception of calmness and passivity because it can mean both exhaustion and concentration, overwork and inactive resistance to it.

Written by Aistė Paulina Virbickaitė

Article published in collaboration with DAILE