RP: You are my sixth interviewee and the first man in my series.

PK: Wow! I feel privileged!

RP: Could you tell me a little more about the nature of your work?

PK: I work across many different mediums. You will find elements of photography and moving image in my practice. You will also find objects, often made out of things I find at flea markets or the internet. I bring them to my studio and remake them into something else. Then there are elements of painting. It’s a new medium for me. It’s quite ironic because whenever I meet new people and they ask me what I do, I reply that I am an artist and the immediate question that follows usually is: ‘so how can I see your paintings?’

RP: So you decided to meet that expectation and started painting?

PK: Well I hope I didn’t start painting because of that (laugh). I do work across many different disciplines. I tend to look at where we are as a smartphone orientated society.

RP: Could you tell me a little more about your works on that subject?

PK: Twenty years ago when the internet started it used 0% of the electricity consumed by humans. Today the internet uses 10% of the world’s electricity and this is the amount that in 1985 was enough to light the entire planet. Inspired by this and other similar facts, I started to produce works on that subject. This series of new paintings and prints, for example, show my fingerprints collected from my iPhone. I produced this work after I found out that, on average, we touch the screens of our phones 5,600 times a day. Put aside hygiene — it shows that our life is dependent on it. What is more, on average we reach out for a phone every six and a half minutes. So in these works, I traced my own ‘journey’ after using the device for 24 hours. I covered the surface of my phone with aluminium powder which is usually used by criminologists to trace the fingerprints of suspects. The results are these really beautiful abstract screenprints that at first don’t look like my own fingerprints. I also used a thermo-chromic ink, which reacts to human temperature. Every time you put your hand on top of the screen print you make the ink temporarily disappear because of the heat of your body.

Piotr Krzymowski in his studio, June 2019, photo: Roma Piotrowska

RP: Wow, so people are allowed to touch it!

PK: Yes, people are invited to touch it, but also when the temperature in the room raises or if the sun hits it, the ink disappears.

RP: What struck me straight away was the painterly nature of it. It’s a painting that we paint every day using our fingers on our phones without realising it.

PK: We are so focused on what we see or what we read, we totally erase the experience of touch. We don’t actually feel those 5,600 touches a day because we are so absorbed with our vision. This work, I would hope, serves as a reminder of this lost sense of touch, of this tactile experience, when it comes to technology.

Piotr Krzymowski, a touch too much, 2019, Screen-print, thermochromic ink on paper

RP: Your paintings seem to be quite far away from your other works…

PK: They are a totally new discipline for me as a medium but also as a process. I cover my body in thermo-chromic paint and it disappears because of the heat. So it feels like having this semi-translucent liquid body on top of me. Then I wipe it with bed linen sheets, because of the extra layer of meaning connected to the marks we leave on bedsheets through the night: folds, sweat marks, makeup marks… it is a mark-making process that we unconsciously do at night. And the paintings are also about leaving traces.

RP: Could you tell me what you are working on at the moment?

PK: I’m working on a video installation that I will be showing at my solo exhibition at the Centre of Contemporary Arts (CoCA) in Torun, Poland. It’s going to be this monumental three-channel installation that shows three different animojis. Animojis are emojis activated by facial recognition and the human voice. Those three animojis will be representing Google Home, Siri and Alexa. The video installation will be a debate between those three assistants, talking about life, death and existential issues. I have spent almost three months in isolation, only being surrounded by Alexa, Siri and Google Home and interviewed them. I have asked them various questions about life, love, their feelings and political points of view. Surprisingly they are coded to answer these questions. And even more surprisingly those answers change depending on how much time you spend with them. Once they learn more about you, the answers are almost shaped according to the personality of the user.

Piotr Krzymowski, When Alexa met Google Home and Siri, video installation, 2019

RP: Could you tell me a little bit more about the exhibition in Torun and how you started working on it? Do you often exhibit in Poland, or is it your first time?

PK: So there’s a funny story about how I met Mateusz Kozieradzki, who is the curator at CoCA Torun. We basically met on Instagram. It is quite unusual for people to have professional relationships on Instagram, but I guess we are an example that it is possible.

RP: What is the show about?

PK: It is called Homo Cellularis which is a Latin term for a human in the era of smartphones. The show is going to look at various behaviours that are associated with the smartphone orientated society. It’s going to look at where we are heading to and what is really left from the humanity…

RP: You have already exhibited Search Engines at CoCA Torun…

PK: Search Engines reveals the nature of the contemporary internet and of our society. The work is based on my journey through the most important internet platforms: Google, Instagram, Facebook and Pornhub. They are four different platforms that represent four different needs and aspects of life. So I decided to use them to see what sort of data it stores about us. I went through every single one of them and typed in the same beginning of a sentence. For example: ‘my husband is’. Google would say: ‘My husband is cheating on me. My husband is having an affair. My husband is boring. My husband is lazy.’ No positive descriptions of the husband. There are no witnesses when using Google, so we allow ourselves to be really open and ask any question. A question we probably wouldn’t ask our best friend! On Instagram, on the other hand, the most used husband hashtag is #myhusbandisbetterthanyours, second best is #myhusbandismylife. So that already shows you great contrast and what sort of altered and curated reality we are dealing with on Instagram. I will leave Pornhub to your imagination… you have to watch the video! This work not only exposes how we want to portray ourselves but also exposes our fears, desires and fantasies.

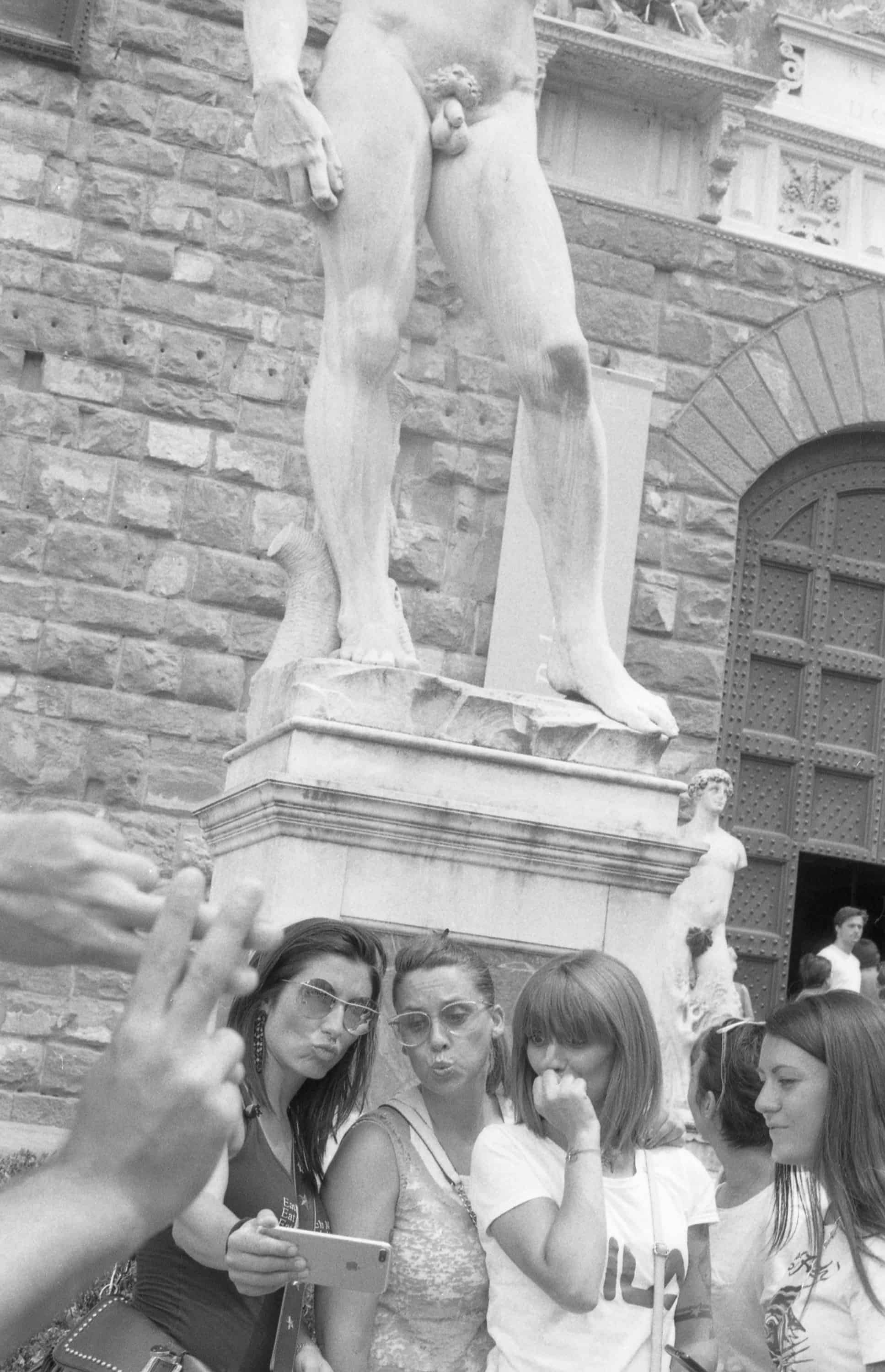

Piotr Krzymowski, #David, 2019

RP: Could you tell me a bit more about your interest in analogue technology?

PK: The interest in analogue has always been present in my practice. My dad bought me my first Zenith camera when I was eight or nine. I had to learn how to use it, it wasn’t as intuitive as it is to use digital cameras. Now everyone is skilled enough to take a photograph on an iPhone. Twenty years ago, when I had Zenith in my hands, I had to choose very carefully what I wanted to photograph. I would choreograph my grandmother and my mother in front of the camera before I pressed the button. Today, I can take a hundred photographs and choose the best one. Back then, I also had to take them to a dark room and develop them. That required another skill and those photographs would always end up in an album. We gathered at my grandmother’s place every Sunday and we would always open our family albums … we had this really great connection with our history. Today, this beautiful ritual slowly disappears.

RP: Has your interest in analogue technology inspired the series of works called Hashtag?

PK: Yes, I think so. Last year, I travelled across Europe with my Zenith camera. I would choose a very hashtagable location or situation, like a monument, a sunset or some sort of activity that is associated with taking photographs for social media, such as eating or working out. I would always ask a stranger to take a photograph of my hands forming the symbol of the hashtag. In most cases they were young people, who had no idea what analogue technology was. They were expecting to see immediate results after they took the photograph. To their surprise, that was not the case! This project shows a contrast between generations, between someone like me who is in his 30s and the younger generation, which didn’t have this experience of analogue photography.

RP: You told me about this nice tradition that you used to have with your family looking at albums together, but now I presume you must live away from your family. I’m only guessing that they are still back in Poland. Don’t you think that social media and the internet allow you to be more in touch with them? That there are certain aspects of the internet that are positive?

PK: I absolutely agree. My ambition is not to be completely negative about the internet and social media – I think they have wonderful aspects, and as you mentioned they enable us to be in touch with each other, but they can’t replace the direct contact. I can’t expect for example my grandmother to be on Instagram. My mum has only recently started to be on Instagram, but she’s not an active user, instead more an observer. Perhaps there will be new traditions and rituals associated with social media, but they won’t replace this beautiful experience of sharing a meal with my family.

RP: Talking about your family and your background, originally from Poland – why did you decide to move to the UK and what was the first thing you did when you arrived here?

PK: I had a very clear idea of what I wanted to do in the UK eleven years ago: I wanted to study art. I had a chance to study at Central Saint Martins which was a very interesting institution offering a totally different educational experience to what I would get in Poland. Art education in the UK is based on ideas and ways of representing them, rather than learning the craft and it was something that I felt particularly attracted to.

RP: And did it meet your expectations?

PK: Yes, it did! This open-minded approach was totally for me.

RP: So your experience at Central Saint Martins was positive and that lead you to exhibit more and more. In 2012 you exhibited at the Bloomberg New Contemporaries exhibition. Could you tell me more about how this happened?

PK: Ever since I started at Central Saint Martins, the Bloomberg New Contemporaries was a dream. It is a group show of a very long tradition and artists are chosen via an open call. Every single graduate of an art school can apply for it. The process is anonymous, so as an artist you basically submit an application with your work and this is how you are chosen. Not by your CV, but by how your work communicates. Being selected to the exhibition really was the beginning of my career as an artist. There’s something beautiful about these open calls because it’s a very democratic way to show your work. I really enjoy participating in open calls. I don’t do them as frequently as I used to, but I still do them.

Piotr Krzymowski, Alphabet (after Amanda Lear), 2017, Video

RP: You’ve actually been recently chosen from an open call to a show at MOSTYN in Llandudno, Wales.

PK: That’s correct, the show opened in July 2019 with my video Alphabet (after Amanda Lear).

RP: What’s the work about?

PK: It is a cover of Amanda Lear’s super hit The Alphabet from the 70s. It’s a really beautiful song where Amanda Lear recites the alphabet, giving an example of a word starting with every single letter. A word that either describes her or describes the feelings of her generation. So it’s not just a self-portrait of the artist, but a song illustrating an era. Whenever I find a new song I really like, I’m obsessed with it. I listen to it almost non-stop. That was exactly the case with Amanda Lear’s Alphabet. At some point, I started asking myself what would be the alphabet of our generation? Especially that Amanda Lear opens her song with this short statement: ‘This is the alphabet of my generation’. The song almost invited me to start thinking about what would be our alphabet. I was trying to find the best words that represent us as a global, digital community. I have again referred to search engines. I typed every single letter from the alphabet and looked for the most searched words that come up. Often you would have names of companies, neologisms, generic terms that highlight us as a fast-paced generation that is always trying something new, is after consumption and rarely looks at the past.

RP: Please describe your life here in London. Maybe starting with your studio?

PK: It’s within Acme studios complex. It was one of the first organisations, originating in the 70s, that was supporting artists with an affordable working space in London. I am very privileged to be one of the artists they are supporting. They have been wonderful. My journey with them started when I graduated in 2012, I was one of eight artists selected for the Central Saint Martins and Acme studios scholarship programme. We were given a brand new, huge space in Stockwell in Acme’s latest development. Apart from being given a wonderful working space, once a month we could also choose a person we would like to invite for a studio visit. When the programme finished, we moved in here as a group of five artists. My flat just happens to be upstairs, so I really enjoy this comfortable situation of not having to worry about catching the last tube home. I can be here any time I want.

Piotr Krzymowski, Swombie, 2019

Installation

RP: Which part of the London art world do you belong to?

PK: I still consider myself as a young artist. I had the privilege of working with commercial galleries, which is great. It is important to support your practice through sales of your work. At the same time, it is important for me to contribute to the non-commercial art world and to be involved in exhibitions at institutions and artist-run spaces. I really think this is where the greatest ideas are formed.

RP: You are not a typical Polish artist. Most Polish artists, especially here in the UK, are interested in history, memory, archives and heavy academic research. Your work is also interested in important topics but I feel like it’s gravitating towards popular culture…

PK: I do look at popular culture, but I don’t see my practice as pop. I have noticed a certain pattern in Polish art though. Even artists of my own age dig down into those aspects of history that are not known to many, but I’m just not one of these artists.

RP: What does your typical day look like?

PK: I like to have a good sleep, but at the same time I like to be a morning person. I guess the compromise is to wake up at 9 o’clock having a nice morning, reading the news…

RP: That’s not a morning person…

PK: What is a morning person?

RP: 6 o’clock!

PK: No, that is a middle of the night person (laugh). So, I like to read the news, have my coffee and come down here to my studio. I like to be here even if I don’t have any specific work to complete. I like to be here, read books, watch films, make notes or answer emails. Sometimes I will come here for 5 hours and not really work on an artwork itself, just the administrative tasks. What else? I love to travel, meet new people. I love many things [laughs].

RP: What are your main influences except the internet?

PK: People who write about the internet. One of the latest fantastic books I’ve read is The Chronicles of Liquid Society by Umberto Eco. It is a collection of short essays he wrote for L’espresso magazine. It contains his observations on digital culture. There is also a fantastic book co-written by Hans Ulrich Obrist called The Era of Earthquakes, a collection of short facts about social media culture.

RP: So the last question… is there anything I didn’t realise I should’ve asked you…

PK: A bonus question! I feel like it should be a special question.

Piotr Krzymowski, Swombie, 2019, Installation

RP: Freestyle.

PK: My freestyle bonus question! I haven’t told you anything about Swombie… Swombie is another series of works I’ve prepared for the show in Torun. I’ve used glass, mass produced mannequin heads. Each of the glass heads is filled with fragments of old electrical devices that I either pulled out from my drawer or have taken from my perfectly functional equipment. Then I filled the heads with either copper sulphate or sulphuric acid, also known as the battery acid. Those two chemicals are used in power stations that feed our online existence and provide us the internet. In large quantities they are extremely dangerous and corrosive, and this is exactly what you see happening with the insides of these heads. You see the process of technology in self destruction. Electrical devices inside the heads will eventually vanish almost completely. In 2015 the neologism ‘swombie’ was voted the German youth word of the year. It’s basically a mash up of two words: smartphone and zombie. It refers to people that are glued to their devices as they walk down the street to the point it becomes dangerous. Cities in Germany and the Netherlands have introduced a special signal for pedestrians which is supposed to wake them up as they cross the street. We tend to forget how harmful technology can be and I’m not speaking about the chemicals that are inside — it is just an illustration of it. More and more people from the younger generations are affected by all sorts of social media side effects.

Piotr Krzymowski in his studio, June 2019, photo Roma Piotrowska

‘Studio Visit’ is a series of interviews conducted by Roma Piotrowska with most interesting Polish artists living in the UK. They discuss their artistic approaches through the prism of the everyday life and recent socio-economic transformations in Britain and Poland. Many of these artists left for the UK shortly after Poland joined the EU in 2004. Thousands of young people, including many artists, found their new home here, studied and matured artistically. In 2019 the UK will step out of the EU, so the present moment seems to be just right to describe a completely new generation of Polish artists. Conversations take place in artists’ studios or houses.