[…] Bogusław Szwacz was born in 1912 in Leżajsk, in Austro-Hungarian Galicia and Lodomeria, still as a subject of emperor Franz Joseph. He belonged to the 1910 generation, which the literary scholars have studied thoroughly, but which art historians seemed to have largely overlooked, even though they contributed so much to the cultural development in our country in the post-war years and well into the contemporary times. The artists born around 1910 are called “witnesses of modernity”, “diagnosts of the time of change”.[1] […] World War II saw them already as adult and mature individuals. They experienced two totalitarian regimes as well as unprecedented civilizational developments. Though they felt responsible for the world, they had no greater hope that it could be improved. It was on behalf of that generation that Albert Camus (born 1913) spoke poignantly having received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1957:

Each generation doubtless feels called upon to reform the world. Mine knows that it will not reform it, but its task is perhaps even greater. It consists in preventing the world from destroying itself. Heir to a corrupt history, in which are mingled fallen revolutions, technology gone mad, dead gods, and worn-out ideologies, where mediocre powers can destroy all yet no longer know how to convince, where intelligence has debased itself to become the servant of hatred and oppression, this generation starting from its own negations has had to re-establish, both within and without, a little of that which constitutes the dignity of life and death.[2]

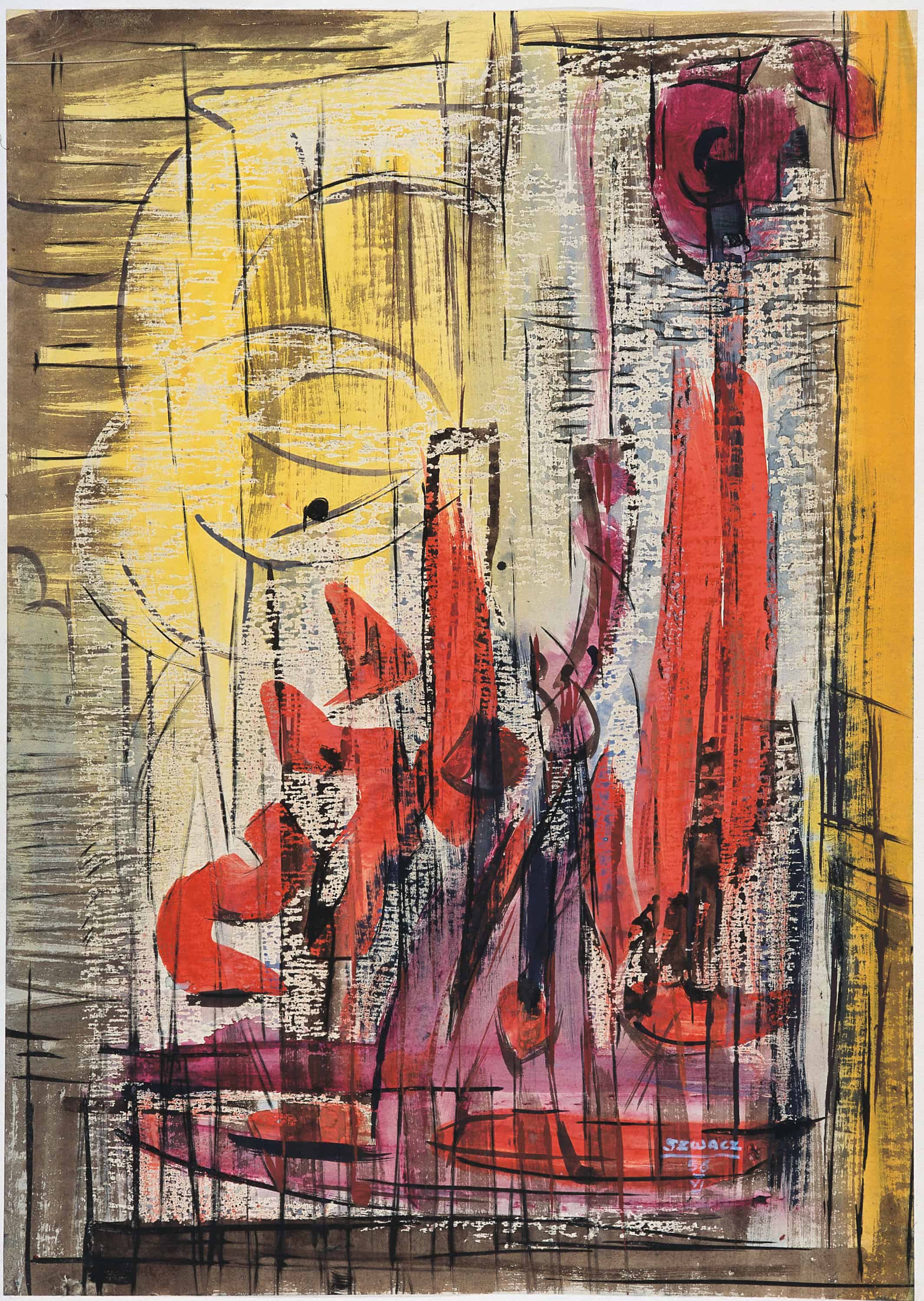

Bogusław Szwacz, Composition, 1948, oil, canvas, photograph by Zygmunt Gajewski

What redeemed and preoccupied Bogusław Szwacz? He was no pessimist, though he judged his age harshly. In one of the late interviews, at 83, he said:

The 20th century is a time of genocide, two world wars, two great slaughters in fact. I took part in World War II myself, defending Lvov. I would have died in Katyń, had it not been for my daring… The 20th century is a century of paranoia. The atmosphere of impatience and unease grew from its very beginning, psychosis was kindled and flamed ever higher… The world had been infected with it already before World War I.[3]

I envision Szwacz as a person of tremendous energy, which sometimes turned against him. He had multiple skills and interests; he played chess and violin, was dedicated to sport, being particularly partial to ice-skating, skiing, horse riding, and swimming.[4] He lived passionately and never surrendered. He would create art, act and draw others into action. He had a sense of mission, which with time brought him close to the avant-garde (and later caused him to drift away from it). He believed that the human can be improved through art, something he applied to himself in the first place. He began with objective painting which he studied long and diligently at the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow (1930–1939). Before the war, he sympathized with the kapists, a group who pursued a moderate programme. Invited by Hanna Rudzka-Cybisowa to contribute to their major exhibition, taking place in 1939 at the House of Plastic Artists, he showed the drawing entitled Cracow Market Square (1938). The war changed his life utterly, precipitating a shift of views on art and society. He was not the only one whose former world was blown away like a house of cards. After many harrowing experiences in which his life was at stake, such as participation in the defensive war of September 1939, work for the underground, escapes, arrests, and forced labour, he managed to settle in Cracow towards the end of the war. He had still more in common with the kapists than the Young Visual Artists Group gathered around Tadeusz Kantor. It was only after the war that he became utterly resolved to join the milieu of the modern ones and, until 1949, grew increasingly radical. “ ‘No risk, no fun’. This is life, as only reptiles and amphibians can grow listless and await a better tomorrow”, he would goad on Kantor himself.[5] In that brief but very intense period preceding the introduction of Socialist realism, Szwacz revealed and developed a trait which was inherently avant-gardist: he desired to be ahead and motivate others to do likewise. Despite the terrible experience of war, he was deeply convinced that a world renewal and transformation of social relationships were feasible, while art would have an important role to play in the process of forging a new human.

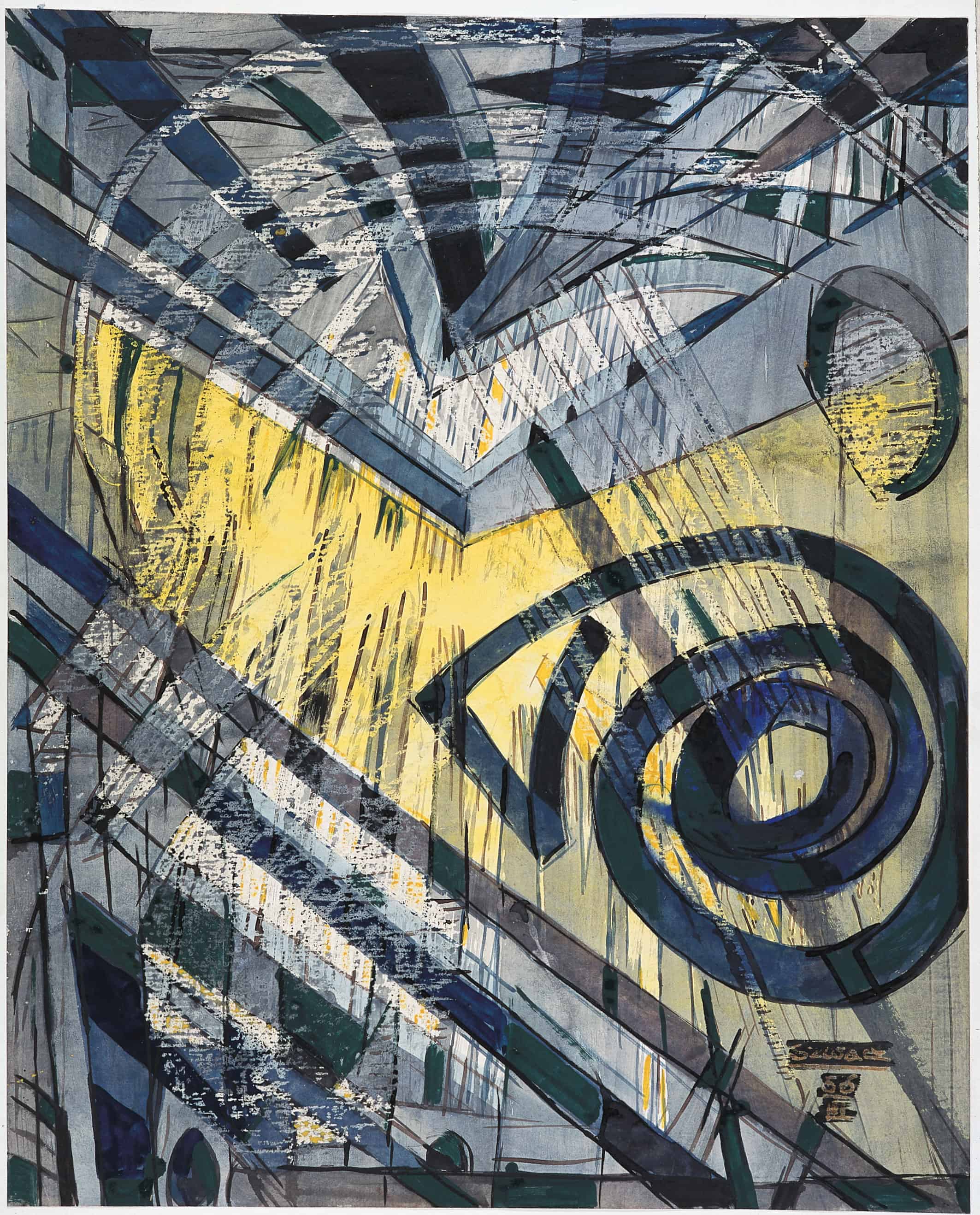

Bogusław Szwacz, Composition, 1956, ink, watercolour, tempera, pastel, paper, photograph by Zygmunt Gajewski.

He shared the faith with a considerable number of modern and avant-garde artists, who after the war sought to lay foundations for a new life. For him, the struggle for new art became synonymous with a left-wing attitude. Once the war had ended, he promptly joined the Polish Workers’ Party, where he was inducted by Maria Jarema and Jonasz Stern, both communists since the 1930s, who consistently combined concepts of new art with the ideas of social revolution. Maria Jarema expressed that forcibly: “And no truly creative artist, due to the very nature of their work, cannot be a bourgeois pig, or a fascist; they serve the cause of progress, even though their political and social awareness were different from ours.”[6] In Cracow, together with Tadeusz Kantor and Mieczysław Porębski, Szwacz contributed in the Young Visual Artists Group, which apart from the aforesaid was joined by Jerzy Nowosielski, Tadeusz Brzozowski, Kazimierz Mikulski, Jadwiga Maziarska, Erna Rosenstein, and Jerzy Skarżyński. He took part in the legendary exhibition of the group at the Palace of Arts, in autumn 1946. Soon enough, however, he moved to Warsaw, where he became associated with the All-Polish Group of Modernist Painters (to which he was invited by Marek Włodarski, Henryk Stażewski, Leokadia Bielska-Tworkowska and Tadeusz Kantor). Also, he became a member of the Club of Young Artists and Scientists. He was active in the painting section headed by Marian Bogusz, along with such artists as Zbigniew Dłubak, Jan Lenica, Maria Łunkiewicz-Rogoyska, Henryk Stażewski, Marek Włodarski.[7] Thanks to collaboration of those milieus, Poland witnessed the greatest pageant of modern art prior to the Stalinist period, i.e. the First Exhibition of Modern Art, which opened in December 1948 at the Palace of Arts in Cracow; Szwacz, naturally, was actively involved in the preparations.

However, still before that event, late 1947 saw Szwacz leave for the much longed-for scholarship stay in Paris (“for further, in-depth study of painting”), which for Polish artists—traditionalists and modern ones alike—remained invariably the most important reference.[8] Quite possibly, it was the last moment when the metropolis of Paris exerted such an intense attraction.

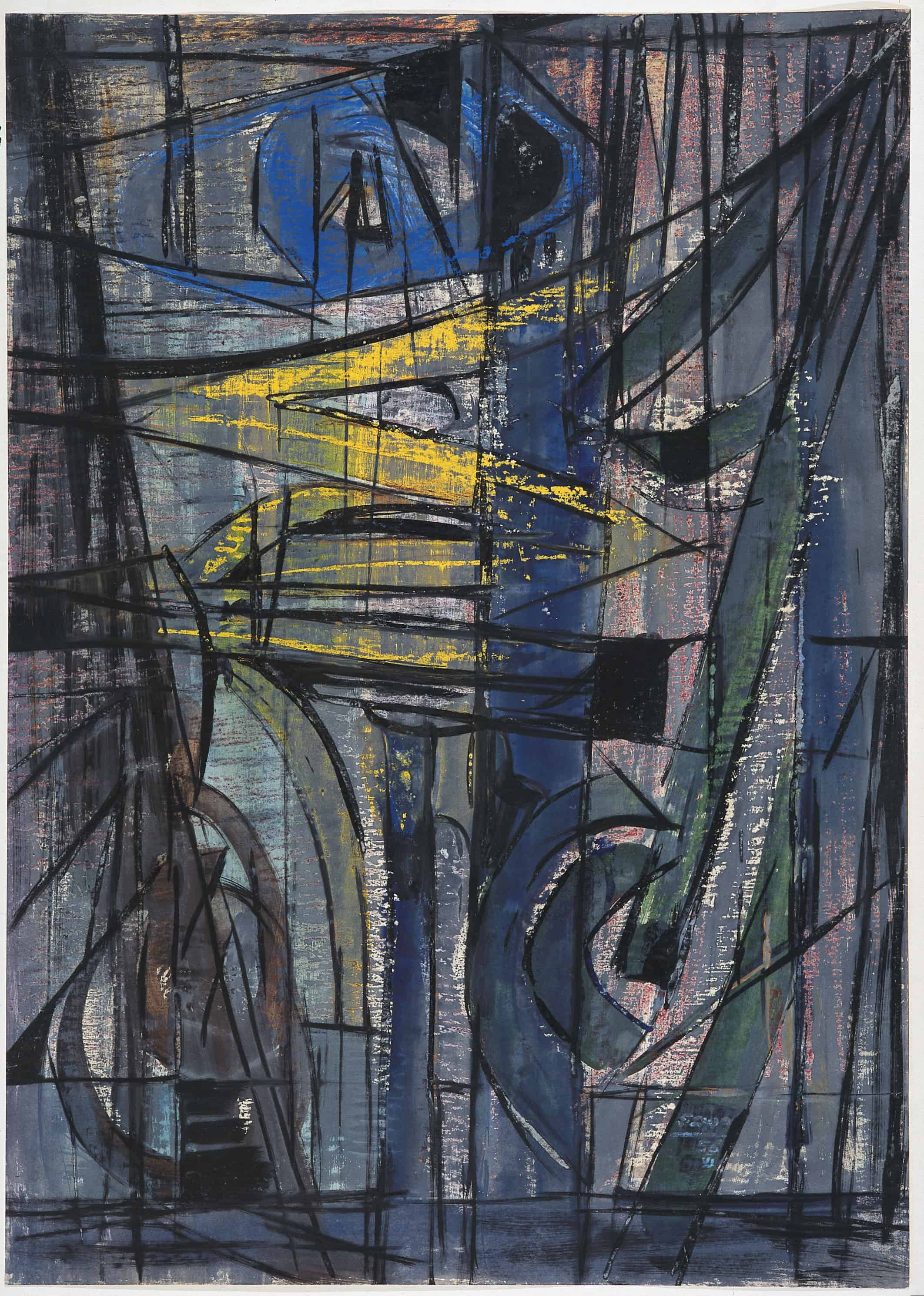

Bogusław Szwacz, Composition, 1956, ink, watercolour, tempera, pastel, paper, photograph by Zygmunt Gajewski.

Bogusław Szwacz, Composition, 1956, ink, watercolour, tempera, pastel, paper, photograph by Zygmunt Gajewski.

[…] Szwacz returned from Paris with notebooks filled with sketches and compositions, many of which are now to be found in the collection of the Piekary Gallery in Poznań. He also came back with a precisely formulated and steadfast notion which art responds to the challenges of the times in the most efficacious manner. Let us remember that right after the war nothing was obvious. In the modern camp itself debates raged and various “isms” clashed with one another. Szwacz went with abstraction. In a dispute with Tadeusz Kantor and Mieczysław Porębski, concerning the imponderables of the avant-garde, Szwacz allegedly said: “Nothing but abstraction!”[9] For their part, Kantor and Porębski were developing the theory of “magnified realism”, which was so vague that it could encompass it all: Realism, Surrealism, and abstraction.

Bogusław Szwacz, Composition, 1956, ink, watercolour, tempera, pastel, paper, photograph by Zygmunt Gajewski.

[…] The collection of the Piekary Gallery contains a valuable source demonstrating how Szwacz built his artistic self-awareness. The portfolio entitled Nine Sketches comprises sheets with black ink drawings on white paper (in a format approaching A5), pasted on a larger, black Bristol paper, on which the artist appended a number of explanatory notes. In a sketch-like manner, the notes deliberate on the nature of abstraction. The last sheet is dated November 25th, 1948, which allows the entire set to be situated in the context of classes with the students of the State Higher School of Plastic Arts in Warsaw as well as the upcoming First Exhibition of Modern Art, an event which encouraged theoretical insights. Szwacz took advantage of the sparing form of drawing with pen and quill (to achieve varied thickness of the stroke), to show the potency of such basic forms of expression. When one reads the explanations, one cannot fail to detect the immense pressure the artist must have been under. Even in notes that brief, he engages in polemics fearing accusations of formalism at the same time. The word hung like a whip ready to strike over everyone, while its meaning changed depending on who used it. Szwacz saw formalism in an approach to art that was tainted by naturalism, “which reduced the visual artist to futile imitation of the phenomena of external, epidermal nature, turning them into copyists, compilers and eclectics.” Szwacz advocates the invigorating novelty of the language of art which only abstraction can ensure. Writing about formalism, the artist employs scathing and polemic terms, but speaks almost lovingly of abstraction: “One who grasped the entirety of visual knowledge, who communed often with the tremendous breadth of forms in plastic art, will hanker after new forms, new worlds.” There can be no doubt that “the abstract work does not imitate phenomena of the surrounding natural world, one which is volatile and impermanent in its epidermal guise: the work of the abstractionist delves into the pith of the inner world that every artist and human being harbours within.” Having recognized abstraction as the ultimate achievement in the evolution of visual forms, Szwacz underlines its profoundly human and simultaneously universal nature. It is a language remote from literature, which exclusively utilizes the most primeval of means:

The image does not tell a story, functioning in the ways of music, dance of architecture: through rhythm, pause, form. Can it be called formalism if the artist seeks a new form conveying the essence of their experience, or the experiences of their milieu, encapsulated in a few strokes or patches detached from naturalistic objects?

Bogusław Szwacz, Nocturne, 1948, pastel, paper, photograph by Zygmunt Gajewski.

Szwacz is convinced of the universal effect of abstract art:

A drawing or a painting of the contemporary abstractionist constitute new worlds, comprehensible to the imagination of every consumer of modern art, as long as they adequately appreciate the stroke, the line, the patch and their correlations on the surface of paper or canvas.

[…] The 1940s, 1950s, and the early 1960s are in my opinion the most interesting period in the oeuvre of Bogusław Szwacz, as it indeed resonates in tune—for good or for bad—with the art of its time. In the latter part of his life, the artist transformed from a belligerent avant-gardist to a more conservatively-minded figure, developing his own Ars-Horme theory, which he called—decidedly in disregard of proportion—an “art of moving the imagination.” The artist, alarmed by the direction in which new art was going (especially the spread of Duchamp’s legacy) aspired to create a new, verifiable creative system, which would prevent excessive liberties. In his Ars-Horme Art Manifesto of 1977, he stressed the uniqueness of the proposal: “ARS-HORME art is different than what has already been in plastic art, and represent that which has never occurred before.”[10] I sense a cognitive hubris in those phrases, which caused the artist to fence himself off against the changeability of the world and art. In point two of the manifesto, he asserted: “The approach of ARS-HORME art inhibits spontaneous reflexes of imagination and guides it towards laborious artistic projects, so that the work may achieve perfection.” I do not claim that the former praise of imagination was supplanted by fossilized notions. Paintings from the Ars-Horme period can be interesting. Yet I cannot help being irked by the need of having the support of words. What some tend to call the poetic oeuvre of late Szwacz, those sonnets going into thousands, are regrettable instances of scribomania with little if any value. The sonnets have been pronounced a “singular manifesto”, in which the author “elucidates his views on painting, music, literature”.[11] I am not going to quote any of it, so as not to mar the perception of the abstract paintings of Szwacz’s from the 1940s and 1950s, whose lyricism is rooted in the spontaneous motions of the patches of colours and lines; paintings which still have their effect on emotions, transmitting their energy to the viewer. I appreciate the synesthetic qualities of Szwacz’s work from the best period, but his later endeavours bear out the warning formulated by Jaremianka: “The picture is the painter’s word. No spoken or written equivalent can express it, for it exists as painting only by virtue of that exclusiveness.”[12]

written by Anna Baranowa

The excerpt from a text written for the catalogue Bogusław Szwacz. Liczy się tylko abstrakcja! Prace z lat 40. i 50. XX w.

Publisher: Galeria Piekary / Verbum Sp. z o. o.

Texts: Anna Baranowa, Agata Pietrasik, Piotr Słodkowski

Edited by: Magdalena Piłakowska, Emilia Chorzępa

Translated by: Szymon Nowak

Photographs by: Zygmunt Gajewski

Graphic design and typesetting by: Ryszard Bienert

Poznań 2018 ISBN 978-83-950525-1-4

The project was co-financed by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage from the Culture Promotion Fund.

Bogusław Szwacz, Composition, 1956, ink, watercolour, tempera, pastel, paper, photograph by Zygmunt Gajewski.

[1]Formacja 1910. Świadkowie nowoczesności, D. Kozicka, T. Cieślak-Sokołowski (eds.), Universitas, Cracow 2011.

[2] After: B. Gautier, “Europejskie pokolenie humanistów, czyli o eseistyce Hanny Malewskiej,” [in:] ibidem, p. 299.

[3] Z. Taranienko, “Kosmos Bogusława Szwacza,” [in:] Bogusław Szwacz. Wystawa malarstwa, [exh. cat.] Warsaw: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych, 1996, p. 6.

[4] Notes of Józef Chrobak, file: Bogusław Szwacz, Cracow: MOCAK Archive, Museum of Contemporary Art.

[5] Bogusław Szwacz. Malarstwo 1946–1956, op. cit., p. 48.

[6] “Maria Jarema; zapiski,” [in:] Maria Jarema. Wspomnienia, zapiski i komentarze, J. Chrobak, M. Branicka, (eds.), Cracow: Stowarzyszenie Artystyczne Grupa Krakowska, 2001, p. 32.

[7] M. Kurzac, Klub Młodych Artystów i Naukowców (1947–1949). Dyskusje i polemiki na temat nowego modelu sztuki nowoczesnej, „Modus. Prace z historii sztuki”, vol. III, Cracow: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, 2002, p. 54.

[8] 4 x Paryż. Paris en quatre temps, [exh. cat.], Warsaw: Galeria Zachęta, 1986; K. Murawska-Muthesius, “Paris from Behind the Iron Curtain,” [in:] S. Wilson et al., Paris: Capital of the Arts 1900–1968, London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2002, pp. 250–261; Mapa. Migracje artystyczne a zimna wojna, Warsaw: Galeria Zachęta, 30.11.2013–09.02.2015 (show also featuring works by Bogusław Szwacz), https://zacheta.art.pl/pl/wystawy/mapa-migracje-artystyczne-a-zimna-wojna [last access: 16.10.2018].

[9] Ibidem, p. 31.

[10] After: Bogusław Szwacz. Malarstwo 1946–1956, op. cit., p. 40.

[11] A. Myjak, after: Bogusław Szwacz. Wystawa malarstwa, op. cit., p. 4.

[12] Maria Jarema. Wspomnienia, zapiski i komentarze, op. cit., p. 34.