“A man performs the same ritual every day: he cleans his shoes, dresses up in his shiny blue suit, wears his white gloves and grey hat, and spends his time walking around Brazzaville“[1] –

This is how the movie Prince (2014), directed by Wojtek Doroszuk, begins. It was recently screened at the Rencontres International Festival of New Cinema and Contemporary Art[2] in Paris and Berlin. This is a major event dedicated to the moving image, with projections and performances. The festival also hosts conferences and round table meetings to shed light on the central questions of the visual in contemporary film and arts practice. Prince is a visual and musical marvel, which embraces characteristic elements of Doroszuk’s artistic practice, and it has been screened on the online Vdrome platform.

Wojtek Doroszuk, Prince, 19’50, 2014, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Joseph Tang, Paris

It doesn’t matter from which work we start to approach Doroszuk’s creative output, because it becomes clear very quickly that this artist takes a unique place as a director and the author of images. As a title, the words ‘A Cameraman’ is just not big enough. Doroszuk strays inbetween fiction, and a documentary approach; an observation, and a subjective impression of a moment; an ethnological field work, and the research of a curious traveller.

We sit with him in a cab going through the streets of Ankara in the movie Birkaç Yer/Some Places (2008), while witnessing a highly subjective guided tour given by Toprak, a well-known figure in the alternative culture of the city. In Reisefieber (2007), we meet the artist himself portraying a season-worker in Germany, struggling with the harsh realities of being an immigrant. Another Doroszuk movie Shalom Chantal (2007), is based around an interview with Chantal Maas, a Jewess who lives on in Oświęcim, despite the history of Nazi atrocities carried out there during World War II.

“On the one hand it is true that I barely work with purely fictional forms, but on the other hand I have made a few documentaries and honestly I feel neither confident in, nor fulfilled by them. However, real places and phenomena, people with their stories, are usually a starting point for my further work. I prefer to treat observational study as a base, as a matter I can cut and fold, manipulate and transform, not as an aim in itself. (…) I intend to create something autonomous, slipping from reportage or classical documentary, respectful for the peculiarity of a place and character, flirting with fiction, yet still anchored in living experience.” – confides the artist himself.[3]

Doroszuk handles his camera with the sensibility of an observer who, seemingly is seeking for a peculiar beauty. In Raspberry Days (2008), the artists is seducing the viewer with juicy colors; magnificent images of Norwegian landscapes surrounding fields of raspberries. Green leaves and forests, a perfection of fruit, and even a rainbow after rain; the viewer can’t stop absorbing this whole vision. Why is it so perfect? Why does the Doroszuk wants us to fall in love with these images, and the filmed landscape?

Wojtek Doroszuk, Raspberry Days, 18’30, 2008, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Joseph Tang, Paris

In fact, the viewer is watching a movie about workers, but workers who don’t want to reveal their faces.

We can only imagine that every day they repeat the same arduous tasks. Like bees, they bustle about collecting the fruit the camera shows us. They are so occupied by their never-ending work, that they may not have time to look around. This awakens the viewers from their idealized visions of labor. Hands of anonymous worker placing raspberries in a container, repetition of movements, and hundreds of fruit bushes to be taken care off – this pristine, perfect facade starts cracking. The viewer comes to understand the amount of work to be done.

Doroszuk’s more recent movies, Festin (2013) and Osad/Sediment (2014), continue this aesthetic approach. In Festin, the presence of people is reduced to a bare minimum, and we can’t see them directly,- just the trace or echo of their actions. Doroszuk takes this a little further, and shows us dogs, peacocks, the fetching of dishes and exotic food, and with all these images, he directs us to older visual traditions of portraying death and nature, as seen in the works by painters like Synders, Potter or Kessels. In Osad/Sediment the camera travels through the ‘back-of-house’ areas of the Arsenal Gallery in Poznań. Crawling worms, used tools and sediment are all that remains of human activity in this space.

Wojtek Doroszuk, Festin, 20’15, 2013, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Joseph Tang, Paris

The reference to the older pictorial tradition indicates that through this game with form and tradition, the artist is asking fundamental questions regarding the human condition today.

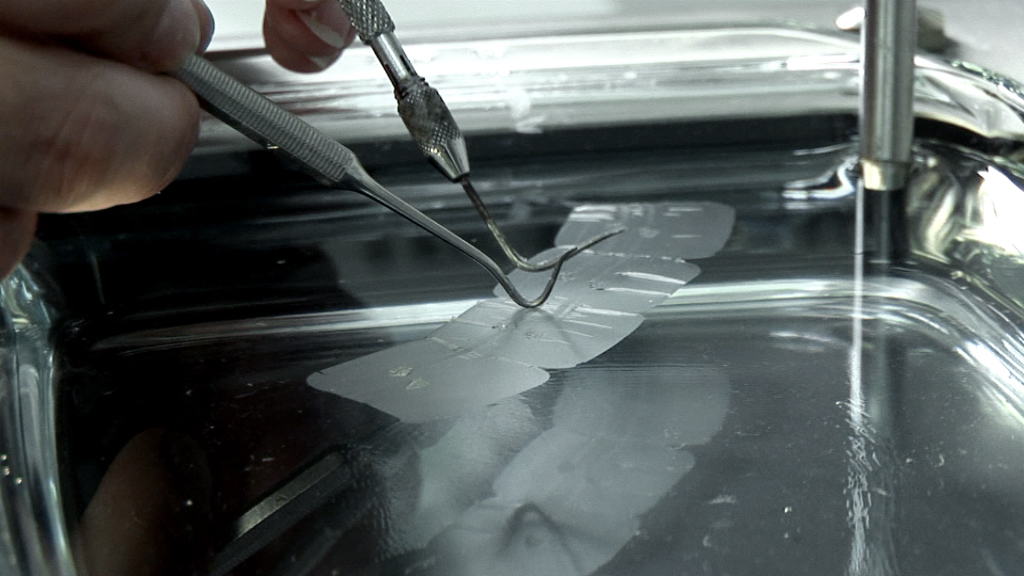

His fascination with terrible, even morbid, beauty is clearly to be see in the subjects and the objects of his movies. Both Dissection Theatre (2006) and Tumor Imaginis (2008) focus on the human body, and the taboos that surround it in Western societies. Both works respectively show dead or sick flesh, which – by a cultural ritual (preparation for a funeral) or by technical processing (biopsy) – are shifted and raised up from the position of being unappetizing (even untouchable), to being the central ‘figures’ of a bigger event. In Dissection Theatre, the lifeless body becomes an object prepared to console a family in a mourning. Meanwhile, Tumor Imaginis shows a scientist fascinated by the beauty of the human body under microscope, where cancer tissue becomes a strange abstract artwork.

Wojtek Doroszuk, Tumor Imaginis, 29’30, 2008, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Joseph Tang, Paris

When Doroszuk travels to film his stories – to another country or just a parallel reality – he works in places and with people on the margins. He seeks out subjects which society has put on the side, as they seem incomprehensible or too difficult to explore. This might be a physical place, like the dilapidated entertainment park in Ankara (Gençlik Park, 2008); the city of Świecie and its ruins of an old mental asylum; a morgue; the streets of Berlin, or the green fields in Norway. Doroszuk registers it all with his camera, which slowly and patiently observes everything, passing form one image to another. Doroszuk goes deep into the meat and bones of a location, and looks to meet people like the ‘Jackson of Brazza’, or Elohim ‘Prince’ Nfsiete. He asks them to walk in the city: Pedestrians interact with him in the street while Doroszuk stays neutral, invisible, entirely contained in the camera which follows the ‘hero’ of the movie. If the camera shakes as the artist follows the Prince, it doesn’t matter. The perfection of the frame will be made clear with the musical sequence. Doroszuk’s camera always registers the objects, people, selected sounds or pieces of conversation with which he builds his universe on film.

Doroszuk’s movies stay respectful for their subjects, and places they were done. Balancing in between the fields of fiction and documentary, Doroszuk has found a space where his style can nourish itself with elements from both: a real story, which becomes the beginning of a ‘film essay’, one in where the camera’s eye intentionally shapes the reality. The artist avoids literal statements and engagement. His search for the root of the human being and being human – understood in a cultural and biological way – investigates this clash between the individual and the complex social structures that surround them.

They are similar,- the Prince walking in the streets of Brazzeville; Dr Frasik talking about the pieces of tissue and biopsies (Tumor Imaginis); Chantal Maas, and the other ‘heroes’ of Doroszuk’s movies. Their stories are told and shared, dispite our contemporary visual culture and mass media, with it’s saturation of high speed flashing images of violence.

http://www.wojtekdoroszuk.com/

[1] From the interview by Steven Cairns for the Vdrome, http://www.vdrome.org/doroszuk.html , seen: 08/02/2016

[2]The Rencontres Internationales, 12-16 January 2016, with the participation of other Polish artists: Dominik Ritszel, Aleksandra Maciuszek. http://www.art-action.org/site/fr/prog/index.php

[3] Vidrome, op.cit.

Wojtek Doroszuk, Raspberry Days, 18’30, 2008, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Joseph Tang, Paris

Wojtek Doroszuk, Tumor Imaginis, 29’30, 2008, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Joseph Tang, Paris

Wojtek Doroszuk, Raspberry Days, 18’30, 2008, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Joseph Tang, Paris

Wojtek Doroszuk, Prince, 19’50, 2014, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Joseph Tang, Paris

Wojtek Doroszuk, Festin, 20’15, 2013, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Joseph Tang, Paris

Wojtek Doroszuk, Festin, 20’15, 2013, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Joseph Tang, Paris