Werner Jerke is the founder of the Jerke Museum in Recklinghausen, the first ever museum of Polish art situated abroad. He’s also an accomplished doctor and winemaker. His exceptional passion for the Polish avant-garde makes him one of the most recognisable art collectors in Poland. This year, Allegro and Contemporary Lynx invited this amazing collector to join the jury panel of Allegro Prize Competition. This conversation offers a great opportunity for familiarizing oneself with his profile and collection or finding out why should artists participate in a competition in the first place, according to Werner himself.

Werner Jerke, private records

DT: What’s your story? Where does your interest in art come from?

WJ: I was born in Pyskowice, it’s a small town near Gliwice in the Silesian Region. There, I passed my final secondary school examination and went on to study geography in Kraków, finished my studies, then moved to Germany. I graduated from a medicine academy in Germany. No one in my family had any interest in art really, though there were definitively a couple of incidents that sparked my interest. First incident occurred in Pyskowice. I was a member of the local film club. It was the best youth film club in Poland at that time, we won all these awards in Łódź. But if you wanted to shoot short films for the club, you had to get in touch with art. The four years I spent in Kraków had also affected me. The Geography Institute was located at the very center of Kraków, so I happened to walk by all the museums and historic architecture every day, in a way I soaked art in. It just went from there.

DT: Yet your interest lies specifically in contemporary art. How did it start?

WJ: I suppose you can’t really say that someone is interested in contemporary art, only art in general – you can’t carve out just a single piece, after all. What you collect is a completely different story because you can’t speak of contemporary art without any background in art history – renaissance, baroque, antiquity, all of it is important. Same with wine – I’m interested in oenology, but I make only certain kinds of wine. In order to make a good wine, you need to be well-versed in winemaking as such. Same applies to art. There’s always one type of wine which is your favorite, which you drink the most. I became fascinated with the Polish avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s pretty early on, especially Kobro and Strzemiński, although I started out with buying works of artists from the Małopolska Region – it’s a natural choice if you live in Kraków. Going back to the comparison with wine, young people prefer sweet wines, but the older they get the more dry it becomes.

DT: What sort of art are you collecting then and favor the most?

WJ: The avant-garde from Łódź rapidly became my forte, not only with regard to art but also to literature – in my collection, there’s almost every book published in the 1920s and 1930s. The second pillar of my collection are the 1950s and 1960s, followed by the third of 1980s, in particular paintings by Gruppa. I’ve always felt drawn to the pieces of art deemed provocative around the time they were created, meaning the avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s, abstraction of the 1950s and 1960s which pushed against socialist realism, and finally the 1980s overshadowed by the introduction of martial law, expressionism of Gruppa and, most important, the political statements – all these works were inciting, going against the tide, so to speak.

DT: Do you recall what was the first artwork you ever bought?

WJ: It was the pastel by Witold Pruszkowski portraying the Aquarius – I still own it until this day, it’s hanging in my house. I found the purchase deeply romantic since I immediately associated it with Świtezianka, a kind of water nymph. The thought that it could’ve been the beginning of an art collection hadn’t even crossed my mind until I delved deeper into the avant-garde. Only then had it occurred to me that I could collect these pieces, and not amass a collection, not yet anyway. There’s a slight difference between gathering and collecting – the latter calls for a direction.

DT: What is art collecting for you? What does it stand for in your opinion?

WJ: First of all, it’s an incredibly subjective activity. Needless to say, some collectors in the world, keeping hordes of art historians on a payroll, view it purely as an investment or speculation. I select the pieces myself so my collection is naturally personal. In fact, it’s personal to such a degree that I never even invite curators to oversee its exhibitions at the Jerke Museum. I don’t think a third party would be able to stage an art show of a fully subjective collection.

Exhibition view, Radek Szlaga, Places I had no intention of seeing, courtesy: the Jerke Museum in Recklinghausen

DT: Would you say that your art collection is the reflection of your personality then?

WJ: If I describe my collection as subjective, then of course it would be linked closely to my own character. No one has asked me that before, but I see your point – I engage in lots of endeavors, so if I hadn’t been a kind of person that sits by the desk their whole life avoiding risks, then I would’ve perhaps collected flowers and still lifes. My lifestyle is quite hectic. I run both a clinic and a vineyard. Maybe you’re right, maybe my collection has a lot to do with my personality.

DT: That’s what I think, taste can speak volumes about a person. In a way, you expose yourself.

WJ: You are what you collect! (laughs)

DT: Exactly! Anyway, you’re one of the few collectors who decided to showcase their collection in their own museum. What was the reason?

WJ: There are two reasons. First one lies in any collector’s nature: every single one of them has the need to display publicly what they’ve gathered. I don’t know any art collectors holding their paintings down in the basement so no one could ever lay their eyes on them. On the contrary, everyone presents their works to a wider audience, although to be fair viewers’ circles vary substantially – sometimes these are your friends, sometimes a group of experts, another time members of the public. Presumably, the second reason is the sense of obligation – we are not the owners of any artwork, they all belong to the society at large. We can’t lock it up for our own enjoyment, we need to show it off. It’s our duty as the patrons of these pieces. I wouldn’t dare to compare my collection to the museums storing the greatest masterpieces ever created, but please imagine Mona Lisa hanging on someone’s guest room wall. It wouldn’t be fair to the entire society because this painting belongs in the public domain, it belongs to everyone in a perfect scenario. Therefore an art collector’s duty is to exhibit their collection.

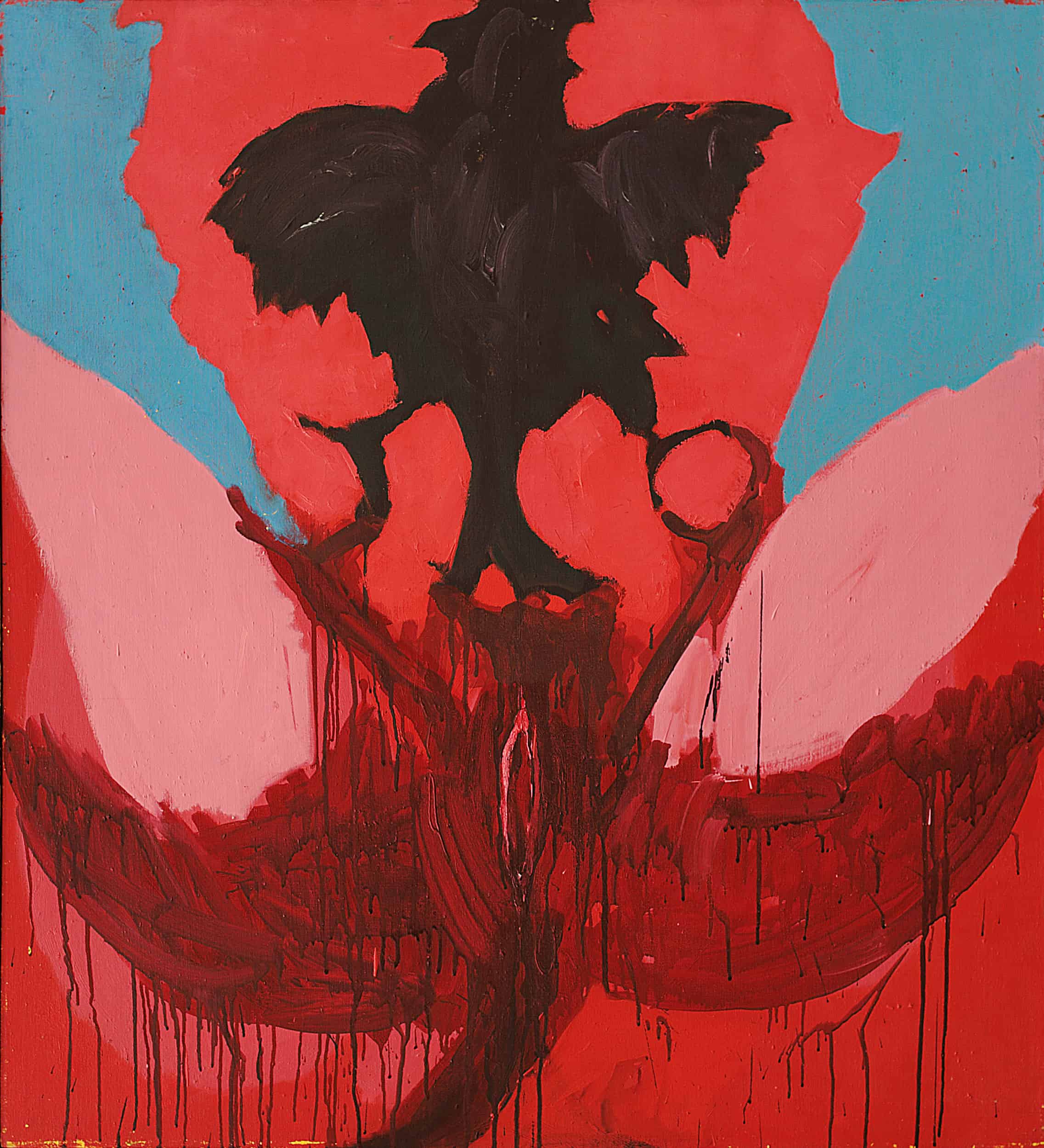

Ryszard Woźniak, Treatment, 1982, courtesy: the Jerke Museum in Recklinghausen

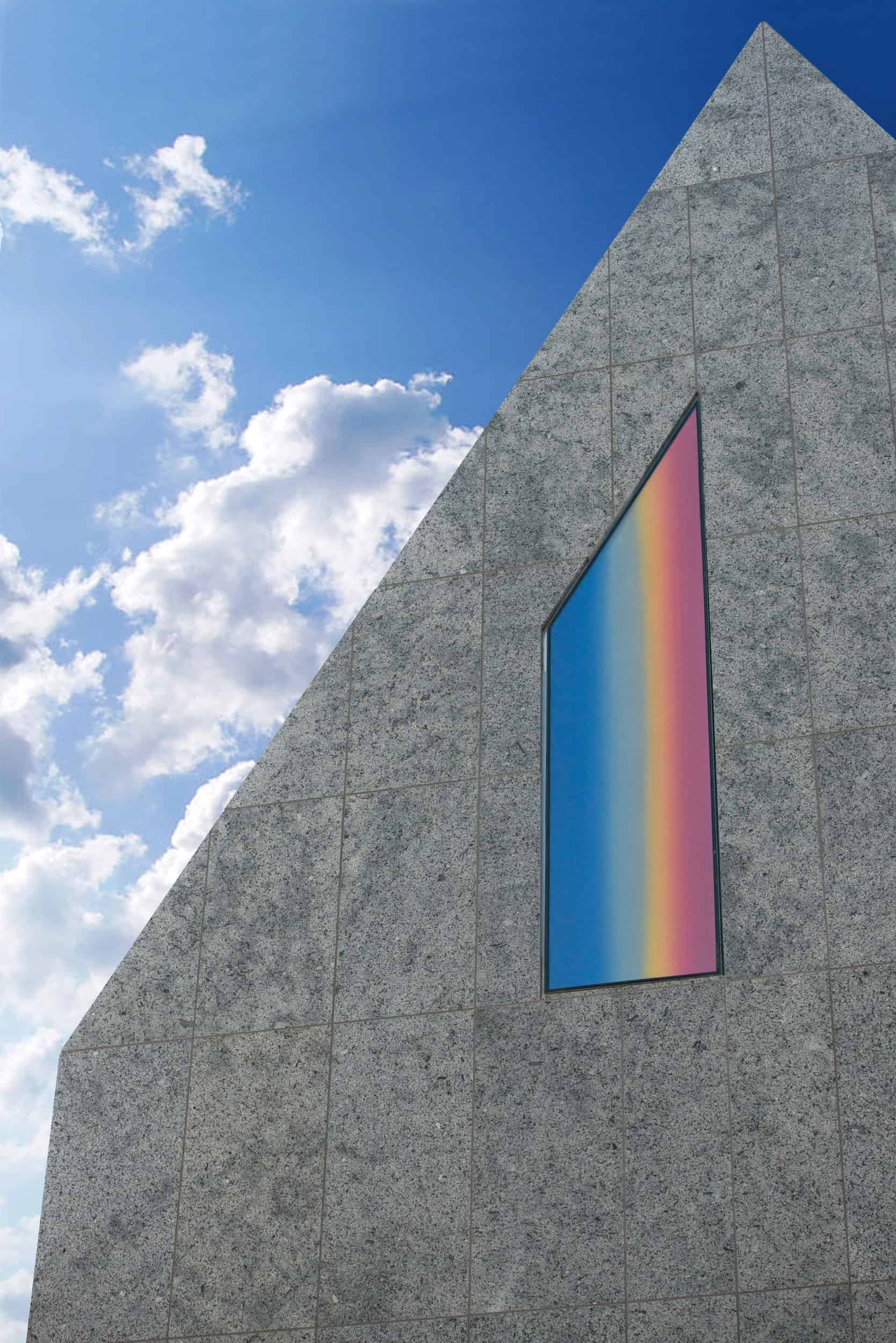

DT: I heard you designed your museum’s seat yourself. How did this project come about?

WJ: The form was adjusted to the old town in Recklinghausen while bearing in mind that provocative art should be displayed in a provocative setting. The body of a museum’s building resembles a monolith, massive rock rooted in the ground. Initially, some citizens expressed their dissatisfaction with design, now we did a 180-degree turn and lots of people can’t imagine the old town without the museum.

DT: Does the Museum Jerke collaborate with other institutions?

WJ: Our collaboration with local museums, such as the Polish Institute in Düsseldorf, brings fascinating results although it was now brought to a halt due to the global pandemic. In addition, I collaborate mainly with institutions based in Poland – for instance Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź decided to include my exhibition of literature and magazines of the Łódź avant-garde in the programme commemorating the 100th year of the avant-garde in Poland. It was one of my greatest achievements and personal joy. I represented a private institution that participated in the celebrations. It meant a lot to me that Łódź, this Polish Vatican of contemporary art, appreciated my art collection to such a great extent. Often, I loan pieces out for other exhibitions, such as the Kobro-Strzemiński exhibit staged by Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź which also travelled to Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, Centre Pompidou in Paris and Kunstmuseum Den Haage. What is more, I work with the Polish galleries and artists whose works are presented at my museum. Last year, I also managed to make a film about Gruppa titled “The Power of Art” in collaboration with the Film School in Łódź. You can watch it on Vimeo and Facebook. I wrote the script and directed it myself, guys from the film school were in charge of production. It was really an amazing experience and immense success. Our collaboration itself was also interesting and intense.

DT: Do you feel you have a mission to promote Polish art abroad?

WJ: Mission to educate is inscribed in the very nature of a museum. Exhibitions of Polish art in the Jerke Museum are visited by the German audience. I once stated in another interview that I was a sort of ambassador of Polish art.

Katarzyna Kobro, Girlish Act, 1948, courtesy: the Jerke Museum in Recklinghausen

Jerzy Nowosielski, White landscape, 1958, courtesy: the Jerke Museum in Recklinghausen

Jarosław Modzelewski, Wall, 1988, courtesy: the Jerke Museum in Recklinghausen

DT: Are you also collecting works by young contemporary artists?

WJ: I buy only what I like. I bought a couple of pieces by Szapocznikow over twenty five years ago, when she was being overlooked. Szapocznikow has risen subsequently to great prominence and these works of hers, which I purchased at that time, landed on the exhibit held by MoMA in New York. However, I always try to view some works by emerging artists and if I happen to like something, I buy it.

DT: What captured your attention as far as new art is concerned?

WJ: Polish art became global. I’m not sure you can speak of “Polish artists” today – I prefer using the term “artists from Poland” since Polish art as such doesn’t exist anymore, there’s only art created in Poland. When you visit larger art fairs, such as Art Basel, you walk by all these gallery pavilions and don’t really get the impression along the lines of “Oh, it’s Polish art so I should stop by”. Young artists and their work no longer carry this national streak, now it’s international.

DT: Does it mean that the Polish and German art scenes are in fact quite similar?

WJ: No, it doesn’t. A large group of Polish artists are represented by the Western galleries and achieve international success. I would just beware of Rej’s geese.

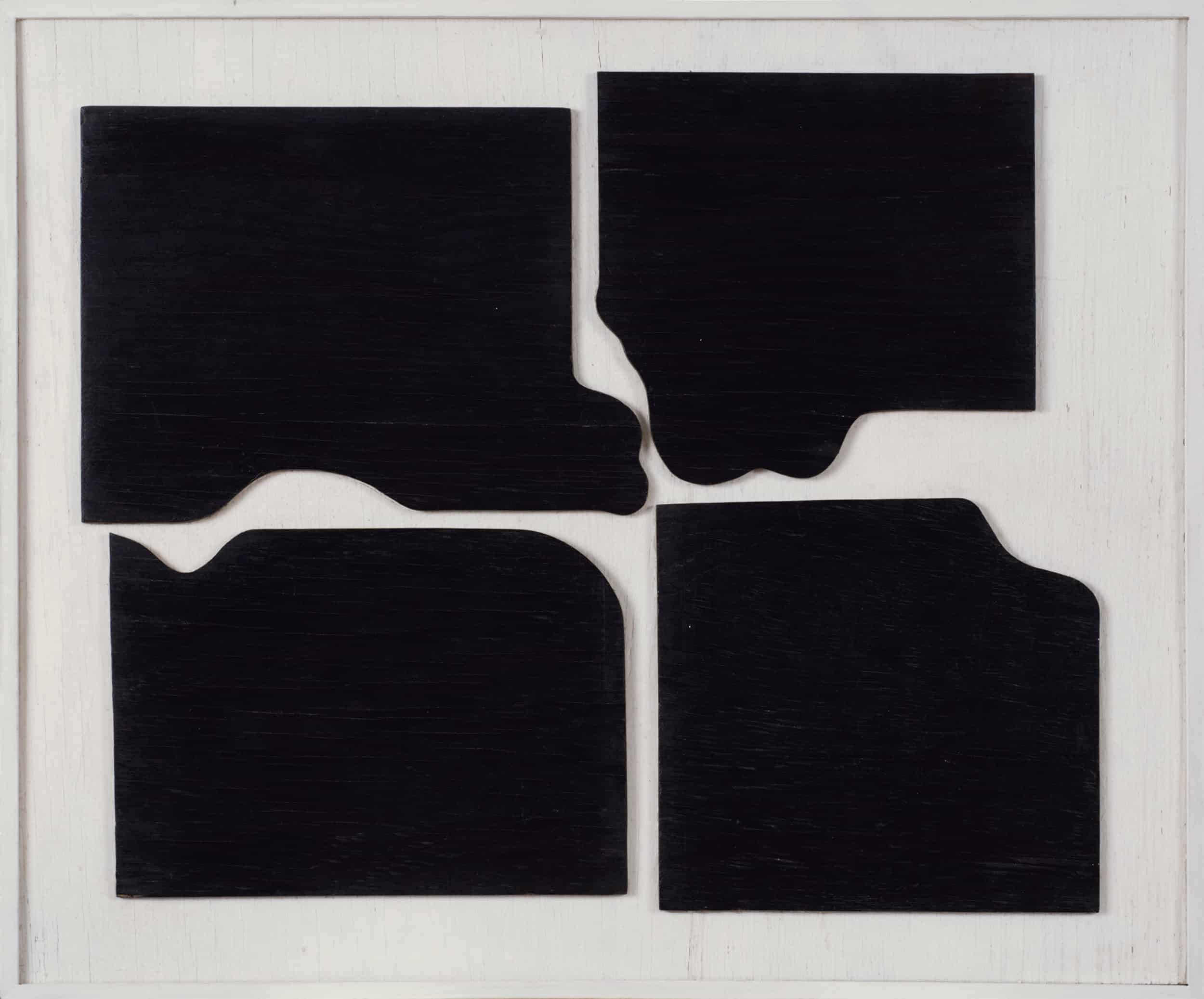

Władysław Strzemiński, Broken rectangle, courtesy: the Jerke Museum in Recklinghausen

DT: What geese?

WJ: Mikołaj Rej said once: “Poles speak not Anserine but a tongue of their own”. I would turn it into “Poles speak not Anserine but an art language of their own”.

DT: What components of contemporary art are the most compelling to you?

WJ: I would rather point at the things that are missing in my opinion, not necessarily compelling. I’m missing the political aspect of art – comparing to the 1980s, it’s now severely lacking.

DT: That’s quite interesting because it seems to me that political activism is thriving on the art scene in Poland, like in the case of “List od Suwerena” – a fairly recent happening which generated quite a media buzz.

WJ: That’s true, yes, indeed. However it only happens in performance as opposed to painting and sculpture, where I feel a gaping absence of it

DT: What benefits do you think could artists draw from Allegro Prize Competition?

WJ: Artists don’t make art just to keep the pieces for themselves just like collectors who don’t collect art just to keep it in the basement. It’s worth going out there and showing what you do. Competitions have the power to attract the attention of galleries, museums and collectors, which in turn provides an opportunity to showcase one’s work to a wider audience. It’s incredibly important to young artists.

DT: Is there anything you will pay a closer attention to as a jury member?

WJ: I don’t want to adopt any criteria. An assumption that I was going to be interested in, let’s say, landscapes only, disqualifies me as a juror. I should stay objective, avoid preconceived yardsticks of success because it would simply make me a poor judge. All artists can enter the competition, not a selected few, so I need to be open-minded. Tunnel vision is not an option.

Exhibition view, Radek Szlaga

DT: Why did you decide to sit on the jury panel?

WJ: First of all, it’s a great honor. The question is hard for me to answer but I suppose I’m simply interested in virtually everything that revolves around art, not to mention there’s this innate curiosity about what I’m about to see. I believe that an abundance of great artworks is going to be submitted for the competition, and that’s exciting, it’s exciting that I could view them all and select those head and shoulders above the rest.

July, 2020

Edited by Franciszek Bryk

Exhibition view, Radek Szlaga