The latest exhibition at the Centre of Contemporary Art Znaki Czasu in Torun, co-curated by Dobrila Denegri and Pontus Kyander, entitled Act or perish. A retrospective is devoted to Gustav Metzger. The exhibition is the first extensive overview of the oeuvre of the artist considered as one of the most important in the 20th century, and spans the period from the late 1940s until today. At the opening of the exhibition, the curators decided to reconstruct self-destructive art demonstrations done by Metzger which involved the painting by acid on nylon. Visiting the display, visitors can see his artworks Supportive (liquid crystals project), Historical photography, Eichmann and the Angel or Light drawings. The exhibition will continue in autumn at the Kunsthall Oslo and Stiftelsen Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo.

Contemporary Lynx’s Anna Dziuba speaks to Dobrila Denegri about Metzger’s exhibition and about Polish contemporary art in a broader sense.

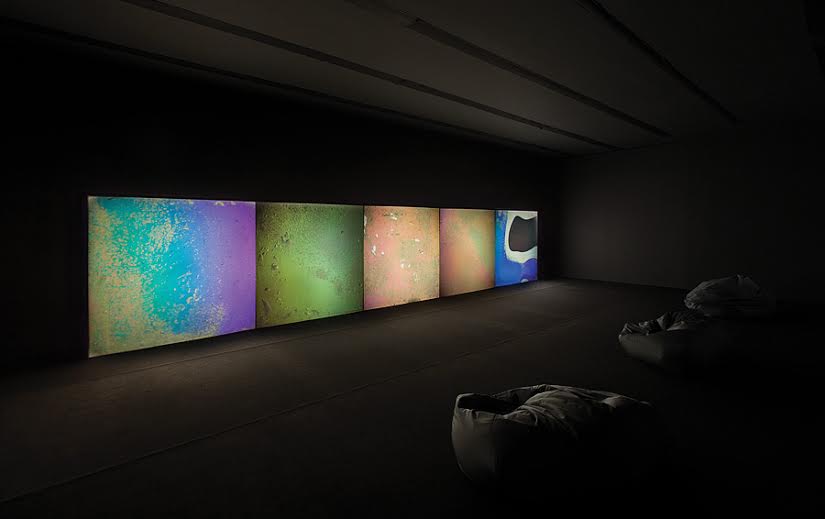

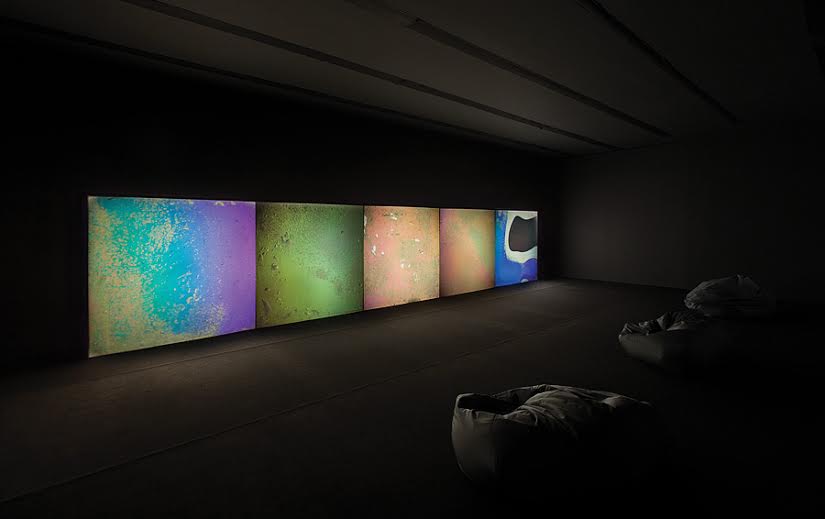

Gustave Metzger, Liquid Crystals Environment, 1965–1998, installation in the Centre of Contemporary Art Znaki Czasu in Toruń, 5 slide projectors, liquid crystals, glass slides, mechanical control, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist and Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst in Zurich, photo Wojciech Olech

Contemporary Lynx: Your last creation was the exhibition of Gustav Metzger’s works. Why do you think his art is important to Polish viewers and why do you think Polish viewers should become familiar with his art?

Dobrila Denegri: I think that today we are gradually losing the sense of belonging to any place, but we are not becoming “Citizens of the World”. Quite on the contrary, we are becoming stateless – in a sense of lacking the state, or as Greek root of the word a-polis indicates, no-polis: without citizenship, without solidarity and without fraternity. So, without rights; neither human, nor civil. Because this seems to be the consequence of the action of biopolitics: the gradual erasing of the rights of man (and citizen) and shifting to post-democracy and/or authoritarian democracy. It’s a direction which our globalised planet, threatened by two huge monsters: politics obstructed by economy and finance and ecological self-destruction, seems to be taking. In the recent re-edition of her classic book Strangers to Ourselves, Julia Kristeva takes a stand against this course. In her preface to the book, she puts the condition of statelessness on a wider, universal level, alluding that it’s becoming common to us all. But for some artists and intellectuals it has been indeed a condition experienced on the direct, existential level. Gustav Metzger is one of them. Born in the family of Polish Jews, he experienced this condition from the early childhood, when brought to England in 1939 under the auspice of Refugee Children Movement. Shortly after, he was left without parents, since they perished in Poland as victims of the Holocaust. Even though still in possession of the Polish passport, for most of his life Metzger moved across Europe with specially issued temporary travel-documents. Still, it is not the question of legal position, but of a condition of being deprived of family, home and country that ushered in Gustav Metzger sensibility and awareness which made him a person and an artist that we know today: engaged, radical and uncompromising when it comes to the question of the ethics in art. Very early influenced by the ideas of Wilhelm Reich, and generally left-oriented and anarchist thinkers, Metzger profiled himself as artist and activist conceptually more upfront than his colleagues, Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff, who shared the same fate of Jewish children refugees. From late 50s, when he distanced himself from the post-war painterly Expressionism and Informalism in favour of more radical and experimental approaches, Metzger became a precursor and pioneer of awareness-raising movements: against political violence, against destructiveness of capitalistic greed, against commercialisation of art. He has been, and is still acting like “a consciousness of the world”, faithful to his initial vow to engage all of his intellectual and creative potential to contribute to social emancipation and well-being of a collective.

So, even as he is approaching 90 years of age, his ideas are still actual and relevant, which is the reason why I think he should be shown today more. Besides, his personal history is interwoven with larger frame of collective history which still so strongly resonates within Polish cultural identity. This is the reason why I thought it would be important to dedicate to him a retrospective in a Polish art institution.

Gustav Metzger, Kill the Cars, Camden Town, London 1996, 1996 / 2011, © 2010 Gustav Metzger, photo Wojciech Olech, courtesy of CoCA Toruń

CL: You open the second part the Gustav Metzger’s exhibition in the Kunsthall Oslo and Stiftelsen Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo. Will it be the same exhibition’s programme as in Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) in Toruń or will it be different?

DD: I think that this part in Toruń can be described as a large panoramic view to Metzger’s oeuvre. In Oslo we want to go deeper to certain aspects of Gustav Metzger works, especially those related to science and cybernetics.

CL: You worked in a few countries as art curator before you started work in Poland. What is your opinion about Polish art; what can Poland be proud of and what could improve?

DD: My father, Ješa Denegri, was probably one of the first curators “in residence” in Poland in the late 70s / early 80s, as a guest of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź and Ryszard Stanisławski. My mother, Biljana Tomić, involved artists like Natalia LL, Zdzisław Sosnowski and others in the big international festivals called “April Meetings” that she was organising in the Student’s Cultural Centre in Belgrade in the 70s. So, even before coming to Poland, I had a great respect for Polish art, considering it one of the highest and most radical expressions of avantgardistic legacies. Of course, today’s Poland is far from the country my parents were talking about. From the point of view of politics or economy – everything changed; but what seems still very present is a high level of intellectual discourse in Polish art. Plus, now there is an emerging generation of artists, curators, galleries who work hard, with a lot of energy, to put Polish art in the wider picture and make it part of the international scene. As one of the very first foreigners to direct a big Polish art institution, I thought that my contribution could be in bringing something different, a view from another perspective to what I perceived as important and characteristic features of Polish art: legacy of constructivist approach in art; legacy of “poor theatre” and generally the theme of corporality, legacy of artistic activism in political and social sphere… With certain exhibitions and general programmatic guidelines of CoCA in Toruń, I wanted to reflect on these particularities of Polish art, but seen from a wider perspective. Thus, I was interested in showing some artists from Polish diaspora, which were less present in Poland, such as Piotr Kowalski, Alicja Kwade… and even Gustav Metzger who is of Polish-Jewish descent. Or I would highlight one of the very important collections which very early sustained Polish art, as is the case of Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo’s collection… Generally I was keen in broadening the view on Polish art, opening up the programme of one Polish institution through a very broad, transdisciplinary and international programme, and this is what I think Polish art scene would have to do more in the future: open up, host and integrate professionals coming from different backgrounds in its art institutions, and take into consideration also other points of view, not just the internally-focussed one.

Gustav Metzger, Exhibition view in the Centre of Contemporary Art Znaki Czasu in Toruń, 2015, photo Wojciech Olech

CL: Do you have any favourite Polish artist? Why do you value him/her?

DD: I can’t say I have just one ‘favourite’ artist. It is too reductive. But if I would have a chance to organise another retrospective of an artist of Polish descent, I would chose Piotr Kowalski. In the Polish context, he is often seen as a French artist, since he left Poland in the mid-40s. He wandered through Europe and South America for a number of years, and finally settled in Boston where he studied mathematics with Norbert Wiener and art with Gyorgy Kepes at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But being part of that generation of scientists conscious of the abuse of scientific research by the US military, he gradually abandoned scientific career, bounding himself up more with the field of art, which remained, together with architecture and urbanism, his main domain of work. Truly convinced that modern man has to be scientifically educated and emancipated, he devoted his life to reducing the gap between natural science and the humanities. That is why his work carries a particular inner coherency as well as ability of interconnecting various fields of experimentation and research through which he introduced a variety of materials and processes into the language of art. His ‘means’ were natural (heat, plant growth, wind) as well as artificial (dynamite, neon, electricity, holograms), they were traditional (granite, steel, glass) and at the same time experimental (rare gas, electrical fields, gas ionisation). But whatever material or media he chose to use, he made the work to function as an invitation for the viewer to become its protagonist and ‘activator’, alluding that in this way a viewer would also ‘become’ an active agent of the broader cultural and social arena.

The exhibition ‘Act Or Perish! Gustav Metzger – A Retrospective’ on show until 30th August at CoCA in Torun

Gustav Metzger, Exhibition view in the Centre of Contemporary Art Znaki Czasu in Toruń, 2015, photo Wojciech Olech

Gustav Metzger, Exhibition view in the Centre of Contemporary Art Znaki Czasu in Toruń, 2015, photo Wojciech Olech

Gustav Metzger, Kill the Cars, Camden Town, London 1996, 1996 / 2011, © 2010 Gustav Metzger, photo Wojciech Olech, courtesy of CoCA Toruń

Gustav Metzger, Pre-historic Photographs: Before the Bombardment of Yugoslavia Blair, Clinton, 1999 and Joschka Fischer, President Milan Milutinovic at the Failed Peace Negotiations at Château de Rambouillet on 23 February 1999, two b&w photographs on PVC,2009, Courtesy of the artist, photo: Wojciech Olech

Gustav Metzger, Exhibition view in the Centre of Contemporary Art Znaki Czasu in Toruń, 2015, on the left: Historic Photographs: The Ramp at Auschwitz, Summer 1944, 1998, b&w photograph, drywall, wood, steel, 330 x 663 cm, Courtesy of the artist, photo: Wojciech Olech

Gustave Metzger, Liquid Crystals Environment, 1965–1998, installation in the Centre of Contemporary Art Znaki Czasu in Toruń, 5 slide projectors, liquid crystals, glass slides, mechanical control, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist and Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst in Zurich, photo Wojciech Olech

Display view, Act or perish. A retrospective Gustav Metzger, photo Anna Dziuba, courtesy of CoCA Torun