In December 2013 Zero Books published Where the Beast is Buried by Joanna Rajkowska, a Polish artist based in London. The book is the first English-language book about Rajkowska, after 2009 publication in Polish by Krytyka Polityczna. It gives an insight into the personal and conceptual roots of Rajkowska’s practice, consisting mostly of public projects executed in Poland, the West Bank, UK, Germany, Turkey and Brazil among others. Her probably best-known (and much loved) piece is the artificial 15-meter-tall palm tree, placed in 2002 at the heart of Warsaw as part of public project Greetings From Jerusalem Avenue. Exploring her oeuvre in the book, Rajkowska takes the reader on an intimate journey that includes her personal, sometimes traumatic, stories, essays by Walter Benjamin and Bruno Schulz, as well as interviews and images providing local context for her projects.

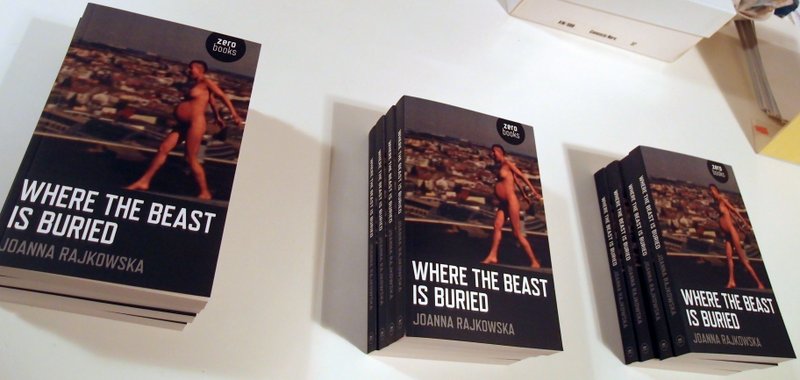

Where The Beast Is Buried is the first English-language book about Polish artist Joanna Rajkowska and her unique practice of work in public space, in extremely diverse cultures and geographies, Showroom, London, January 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

Contemporary Lynx attended book launch on 14 January 2014. Hosted by London art space The Showroom, the event had Rajkowska in discussion with Sarah McCrory, director of Glasgow International, and Sebastian Cichocki of Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. The room was pretty filled with interested audience and included two little girls, one of them the artist’s daughter Róża, roaming freely.

Opening the evening, director of The Showroom Emily Pethic highlighted how appropriate it was for them to host the event, reminding of Rajkowska’s project Chariot from 2010, shortly after the gallery had moved to its current location in the Church Street Ward in West London.

Book launch – Where The Beast Is Buried by Joanna Rajkowska, Showroom, January 2014, London, photo Contemporary Lynx

Joanna Rajkowska emphasised how writing about her practice is important: what is not there in the immediate experience of the project, presents itself in language, making it ‘the most precise instrument of analysis’. Writing is always about translating her projects through language and her own body that becomes a filter. Interested in a singular body embedded in the landscape as well as in the feelings present there, Rajkowska rejects the idea of compulsory participation of the audience in her projects. Laughing, she explained that herself she would hate being asked to participate so her approach is grounded in respect for the audience. It sounded very refreshing among the current trend to make performance art ‘participatory’ and ‘interactive’ at all cost.

Joanna Rajkowska in discussion with Sarah McCrory (Glasgow International) and Sebastian Cichocki (Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw), Book launch – Where The Beast Is Buried by Joanna Rajkowska, Showroom, London, January 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

Crucial for Rajkowska is understanding of public projects as organic entities that live, grow and age, and also die at some point. From numerous projects described in the book, Rajkowska chose to talk about The Peterborough Child. Started in 2012 and still described as ‘ongoing’, the project may soon become ‘dead’ or at least a kind of failure. The artist’s idea in Peterborough was to create a fake archaeological dig, a representation of the grave of a baby girl in a pit 1.5m deep and covered with glass. Rajkowska talked about the conflicts on the ground, most acute one between local Afghans and Palestinians, as well as about her personal tragedy: as the work on the project started, her baby daughter was diagnosed with eye cancer. Because of that, first she wanted to transform entire city into a blood circulation system and designed giant red blood cells that would be scattered around. This didn’t go down well with the city officials: blood was seen as potentially incendiary, reminding of past violence. To her disappointment, the grave didn’t materialize in public space either: representatives of the orthodox Muslim majority rejected the piece without even seeing it. It also transpired that high infant mortality rate and anxiety amongst women about using NHS services are severe problems in the area. The project got relegated to the local shed.

Joanna Rajkowska, The Peterborough Child, 2012 – ongoing, Peterborough, UK, Commissioned and produced by: the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce and Citizen Power Peterborough, image courtesy of Artist & Zak/Branicka Gallery

Joanna Rajkowska, The Peterborough Child 2012 – ongoing, Peterborough, UK, Commissioned and produced by: the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce and Citizen Power Peterborough, image courtesy of Artist & Zak/Branicka Gallery

Continuing the theme of organic nature of public artworks and their lifespan, Sarah McCrory compared public art pieces to tattoos on the city’s body and asked Rajkowska how she felt about her projects aging and perhaps finally dying, to which the artist replied without hesitation: “They are like children, they don’t belong to me”. She seemed completely OK with letting go of her projects, letting them live their lives without her.

The conversation took an interesting turn as Sebastian Cichocki wondered about art projects in public space as imposing the spirit of ‘togetherness’ on local audiences. Rajkowska explained that just as she doesn’t demand participation from her audience, she has no intention to induce ‘community spirit’. She wants the viewer to position herself in the work, to relate to it on a personal level, to have perhaps visceral reaction to it. Admittedly, her work may have such a strong impact that people on encountering it feel raw, ‘naked’, and so overwhelmed that they shut down, which can be seen as preventing community building.

As her train of thought took her elsewhere, Rajkowska did not talk about alternative scenario: the possibility of people coming together after being transformed by the experience of her project. Enthusiastic about the event of essential human connection on a personal level, Rajkowska remains sceptical about the possibility of ‘community’ in contemporary society; any togetherness created around her works remains for her merely a ‘side-effect’.

Refusing to accept moral or religious prohibitions that have their source in the communal modes of life, Rajkowska asserted she’d always strive for personal connection with the other, trying to touch them on the most intimate level. However, it is precisely by looking through the community lens that we can understand why for example Peterborough “wasn’t ready yet” for the faux-archaeological grave of a baby girl. A testament to her artistic integrity, Rajkowska admitted that even though the project turned out to be a failure, she wasn’t prepared to move it to a gallery somewhere else. Doing her investigations in public space is the crux of her practice and so her projects don’t get to have a ‘second life’ in a gallery. The re-enactment, with objects and concrete bodies, needs to happen in the particular place, infused with feelings and energies.

Book launch – Where The Beast Is Buried by Joanna Rajkowska, Showroom, January 2014, London, photo Contemporary Lynx

The inspiring evening was both a good primer for those not too familiar with Rajkowska’s practice and a great opportunity to ask detailed questions by those following her work closely. The artist gracefully imparted beacons of her practice, not afraid to show her own vulnerability. A certain degree of hopelessness about the world is always a good place to start; the political can be found in the most intimate, intense places of our being and teased out of there by means of dreaming and fantasy.

PS. Encouraged by the meeting to further online research, I found some bad news for the palm tree’s fans: its location is currently under threat due to a draft of urban development plan for the part of Warsaw it’s in (article in Polish).

Joanna Rajkowska and Sarah McCrory (Glasgow International), Showroom, January 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

Biography:

Joanna Rajkowska is a Polish artist based in London, working mostly in public space. She produces objects, architectural projects, geological phantasies, excavation sites and ephemeral actions that are essential parts of her widely discussed public projects. Rajkowska’s artwork has been presented in the UK, Germany, Poland, France, Switzerland, Brazil, Sweden, US, Palestine and Turkey, among others. Her public projects include comissions by CCA Zamek Ujazdowski (2007, Oxygenator, Poland), Trafo Gallery (2008, The Airways, Hungary), Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (2009, Ravine, Poland), The Showroom (2010, Chariot, UK), British Council (2010, Benjamin in Konya, Turkey), 7th Berlin Biennale (2012, Born in Berlin, Germany), Royal Society of Arts, Citizen Power Peterborough programme’s Arts and Social Change, Arts Council England (2012, unrealised project, The Peterborough Child, UK) and Frieze Projects 2012 (2012, Forcing a Miracle, UK).

Ania Ostrowska moved to London from Poland in 2005. Enabled by her country joining the EU, she got an MA in gender studies from SOAS, University of London. She lives in the London borough of Hackney and divides her time between working part-time at the Wellcome Library and being film editor for the biggest UK feminist blog The F-Word [http://www.thefword.org.uk]