This time we would like to present you an interesting conversation with Dr Werner Jerke, which took place during the Art Basel fair. This German ophthalmologist is a collector of Polish contemporary art and a big promoter of Polish culture in Germany, which is very well evidenced by his latest great initiative in building a Museum of Polish art in Recklinghausen at the Ruhr district.

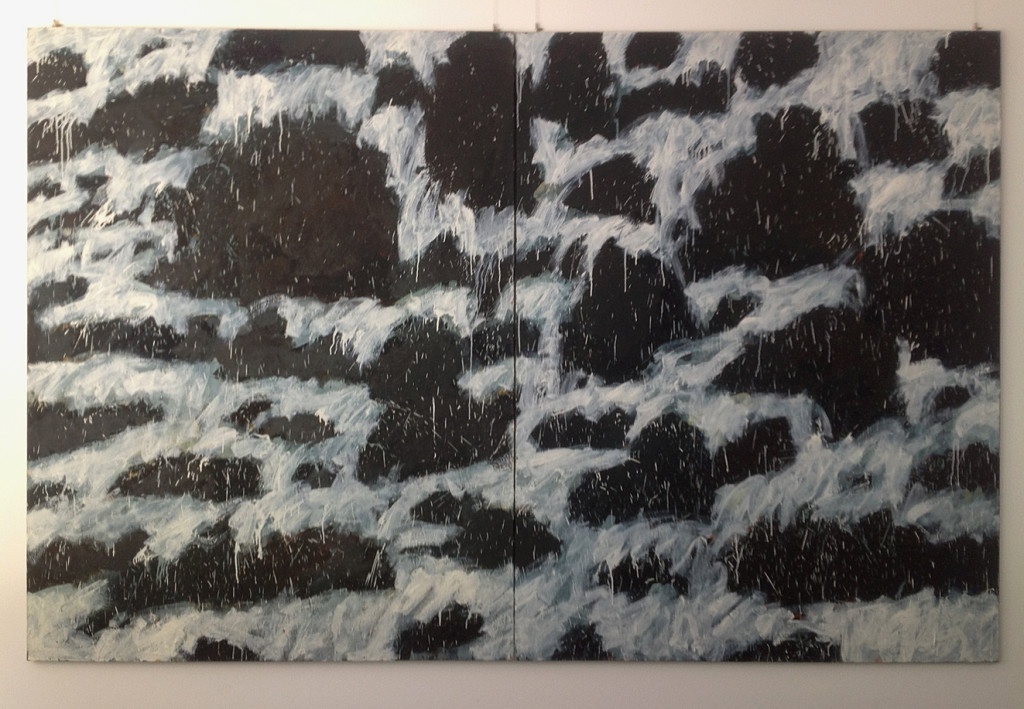

Tadeusz Kantor, Informel, courtesy Dr Werner Jerke

Contemporary Lynx: The Art Basel fairs have just started. It is one of the most important art shows in the world. Poland is represented by two galleries. Let this event be a pretext for a conversation with the collector who holds one of the greatest and the most important abroad collections of the Polish art.

Are You going to Basel this year?

Werner Jerke: Unfortunately I have to say: no. For the first time since few years I didn’t go to Basel due to the construction works of the Museum… I had a free week, specially reserved for the Art Basel, but during this time we had few meetings with the architect. This year, the Museum was more important than Basel. But, in general, yes, usually I go to Basel every year.

CL: Do You have some favorite art shows?

WJ: In total I have three favorite art shows in which I participate. It is Art Basel, Art Cologne and TEFAF Maastricht. Maastricht is probably less popular in Poland. These art shows present not only the modern art but an art in general. There are the old masters, the African and the Ancient Greek art, books and the jewellery of the highest quality and what interests me the most – the art of Oceania, for example masks and reliefs. The additional advantage of Maastricht is that every object which is being delivered to the art shows is checked by an appropriate commission. The commission is organized by the art shows and is composed of the experts in narrow fields, specialized in the modern art, the ancient art, the books and design. Every object is checked by them what ensures the highest quality of the objects presented during the Maastricht trades. These trade fairs are also very expensive for the visitors what makes that lots of people go there to introduce themselves on the market.

The Art Cologne fairs are developing more and more. These trade fairs, and not the Art Basel, are the oldest ones. It’s a pity that in Cologne there are so few Polish galleries.

CL: Does it happen to You to buy works during these art trade shows?

WJ: Yes, I’ve already bought some things during the trade shows, however, the most important ones I’ve purchased outside the art shows.

CL: Collecting is not only buying but also “leading” a collection. It often happens that the collectors lend the works, organize the open exhibitions of their collections, publish catalogues and books. The works from Your collection are shown on exhibitions. Recently, the artworks by Alina Szapocznikow were presented on the notorious retrospective exhibition i.a. in the MoMA in New York. At the end of 2012, the artworks of Samuel Szczekacz were presented at the Atlas Sztuki. Do You lend the art works willingly for the exhibitions / do you like sharing them with a large audience?

WJ: As regards Alina Szapocznikow, indeed two of her works coming from my collection were shown in the MoMA. Three drawings of Władysław Strzemiński will be now lent for the exhibition in Norway. You know, in my opinion, if someone is an owner of a piece of art it’s not only his property. The masterpiece belongs to the society in general and I’m only lucky enough to keep it for a moment. Everybody leaves this world some day and somebody takes his belongings. Now I’m lucky to possess it, but in fact, it’s not mine, so I feel obliged to show to the people the art works from my collection and not to keep them only for my own pleasure. I like to lend the art works for the exhibitions, but I have to highlight that for lending your collection you don’t get anything in return. Probably sometimes it’s harmful for the art works and stressful for the collector. For instance, these two mentioned art works of Szapocznikow were not only in NY, but also at the Hammer Museum in LA, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus in Ohio. As a result, I didn’t see them for almost a year. I treat them as if they were my kids and You can only imagine that when they’re away from home for over a year, “daddy” is starting to worry about how they’re going to come back. To sum up, it’s stressful but I lend the art works willingly.

Alina Szapocznikow, Fajrant (End of Day’s Work), 1971, polyester resin, rubber glove, brush, 26 x 16 x 11 cm, courtesy Dr Werner Jerke

CL: You went even further, You’re planning to open a Museum…

WJ: As I’ve already said, I think that the art is a common good which belongs to the society no matter who is it’s actual owner. Lending the art works was a step forward to share some masterpieces but as a final result I’d like to show the greater part of my collection. The one and only possibility is building the Museum. It won’t be a building of the dimensions similar to those of MOCAK in Cracow. It’ll be a lot smaller but I hope to show there lots of interesting works. Many of my friends collect the Polish art. The paintings of Polish artists are hanging inside their houses. However, I think it’s still too little. I’d like the greater part of the society to know the Polish art.

CL: Where did this idea come from?

WJ: Every collector probably dreams about it. You only have to take it in your own hands and make the dreams come true. The problem I faced was to convince my family. Building a museum and running it is not much of a business. It’s an expensive hobby. Fortunately, I managed to persuade my wife and my daughters that I want to make my hobby more public.

CL: Will the Museum collection include the art works from Your collection?

WJ: Yes, it will. I’d like my collection to become a permanent exhibition.

Jarosław Modzelewski, Murek, courtesy Dr Werner Jerke

Andrzej Wróblewski, Portrait of a Woman, courtesy Dr Werner Jerke

CL: What will be the programme of this institution? (temporary exhibitions, permanent presentation, projects of the cultural exchange?)

WJ: I don’t have a concept as regards the construct, however I’d like a Foundation focused exclusively on the Polish art that would function in the Museum.

I’d like to manage to organize there, once or twice year, the exhibition of Polish modern artists. I have good relations with a great number of Polish galleries. It seems to me that if I managed to organize such exhibitions in Germany, it would be something interesting. I wouldn’t need to play a curator. This would belong to the people who are specialized in it. Katarzyna Sokołowska, the Director of the Polish Institute in Düsseldorf likes this idea. In the future, I’d like to do something in the framework of this Institute.

Financing the chosen artists would be the next step. As You may know, since few years we’re sponsoring the meetings of the Polish geometry artists, now in Warsaw, before in Orońsko, led by the professor Bożena Kowalska (editor’s note: the exhibitions in the Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, the Mazovian Centre of Contemporary Art “Elektrownia”). Supporting the artists, also financially, is the essential point of our project.

To sum up, the Foundation would carry out three basic functions: maintaining the collection, organizing the exhibitions and eventually supporting the artists.

At the beginning, the Museum should be open on Friday and Saturday. Firstly, I have to see how big is the interest and how does it work. I don’t want to keep it open all week long if it happens that there’s one visitor every two days. If the interest is big enough, I’ll think about the stuff.

CL: Where will the Museum be situated?

WJ: I managed to buy the building in the very center of Recklinghausen, nearby the Museum of Icons – the biggest Museum of icons outside the orthodox countries. This is a really beautiful building and I’m glad that we will function next to each other. It’s situated nearby the oldest square in Recklinghausen. Nowadays, the archeologists are there on a dig because the building is located in the area where previously was situated the mansion founded by Charlemagne. On this square, between the Museum of Icons and my Museum an old well was discovered and the city is planning to renovate the whole square. As a result, it wouldn’t be on the outer periphery of the city but in its heart. I hope that all this will make more people visit my Museum.

CL: This meeting of different cultures, histories and modern art make appear new contexts…

WJ: I agree, it would be the contrast between the medieval art, the orthodox icons and Polish art. It would be quite an interesting place.

CL: When is the opening planned?

WJ: It depends on the archeologists, on whether they find anything. If they do, the opening day may be postponed. Nevertheless, I hope that we will be able to open this Museum the next year.

Wojciech Fangor, courtesy Dr Werner Jerke

CL: Where did You got the interest in art?

WJ: I don’t know (laugh). I’m interested in art since a long time. I suppose that it began when as a child I had a car accident and I was in hospital for five months. It happened in Poland in the 70s. There was no TV in the hospital so I read a lot of books, it was the only entertainment. When I had read all the teen books, the librarian brought me a book about the French artist, Maurice Utrillo. It was my first approach to art. Later, I started reading more and more books on that subject. After passing my matura exam, I moved from my small village Pyskowice, located nearby Gliwice, to Cracow where I started my geography studies. The studies in Cracow are something really extraordinary. You have a contact with art at every turn – and this is what made the biggest impression on me. At the beginning, it was indeed under the influence of that city, that I started buying works from the Young Poland period.

As for Utrillo, when my apprenticeship in medicine here in Germany was well developed I bought his small watercolour painting (he painted an incredible amount of paintings). What’s interesting is that this work had been already shown on the exhibitions in Japan four times, yes, exactly this one – it made me so happy.

However, it was in Cracow where I felt the real passion for art. At every turn there’s some museum or historical monument. It’s probably the only European city where there’s an interaction of so many historical eras in one place. For example, when you’re walking down the Grodzka street you can notice the Romanesque art neighbouring the Gothic, Baroque and modern art. During the studies I lived in the dorm and every day walked down this street to the Geography Institute nearby the Royal Wawel Castle. Such things affect you. After my studies I went to Germany to study medicine but during that period I was going back to Poland very often, to Cracow and to Warsaw. Thank God, my financial situation was good enough so that I could afford the higher class art works.

CL: Do You remember Your first purchased masterpiece?

WJ: The first work I got was the painting by Witold Pruszkowski, „Aquarius”. I bought it in a gallery in Cracow which doesn’t exist anymore but its owners still have an antique shop. I bought my first painting from them.

CL: So You started collecting the turn of the century paintings?

WJ: Yes, it was due to Cracow. However, immediately after it was the avant-garde that started intriguing me.

CL: Does Your collection has a specific profile, so You collect the paintings dating from concrete time periods, or You select them at certain angle?

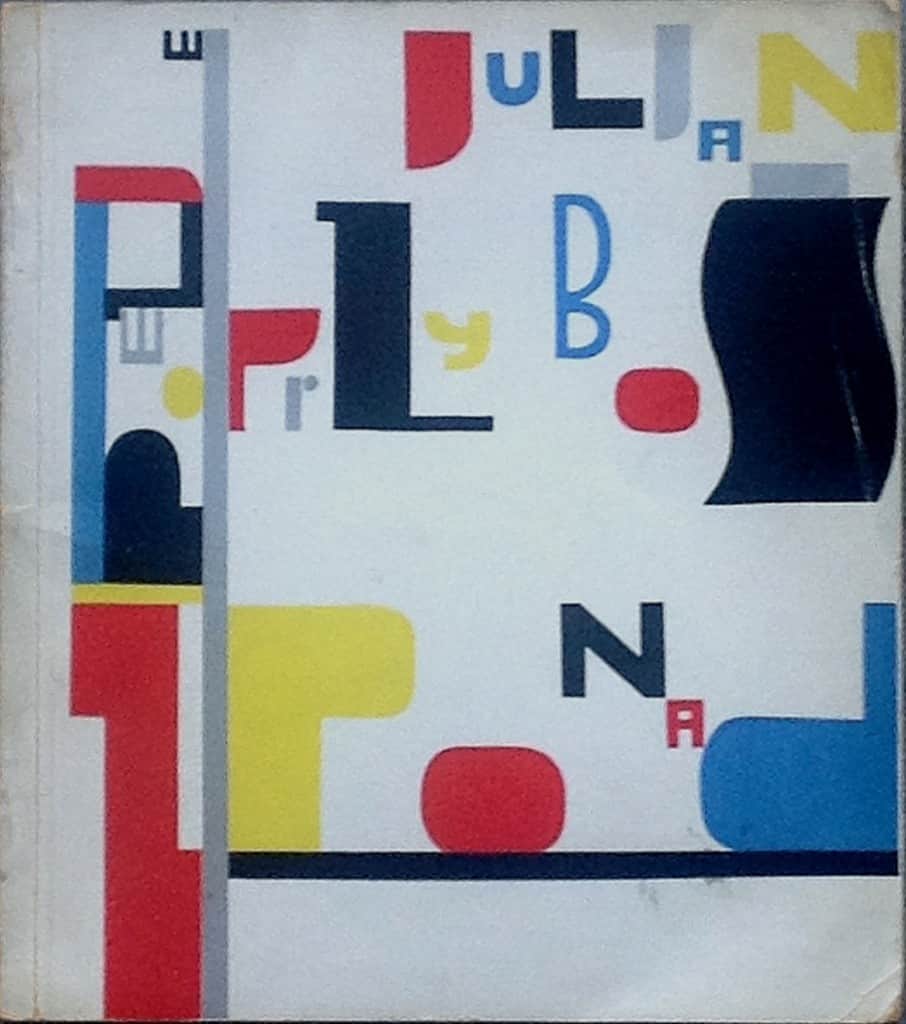

WJ: I could divide my collection in three groups. The first one is composed of the Polish avant-garde – 20s and 30s. However, there are not only the art works. I’ve collected also almost all publications concerning the 20s and 30s (only in Poland). In my opinion it’s one of the best and most interesting avant-gardes. For instance, look at the cover of the book of poems by Julian Przyboś, “Śruby”, “Z ponad” (“Sponad”) or at the covers by Władysław Strzemiński – is there anything better to see about that period? The second group of my collection, not so ample and a bit “aside” group, represent l’École de Paris – Henri Hayden, Leopold Gottlieb, Louis Marcoussis. The third one is composed of the art works dating from the 60s to nowadays. It is the group I’d like to show in the Museum. I’m thinking about constructing a small wing dedicated to the art of the 20s and 30s but I have to think it over once more. If I made up my mind I would like to cooperate with some curator, maybe Polish one, who would help me present all of this properly.

Book: Julian Przyboś , “Z ponad” (From Above) , cover designed by Władysław Strzemiński (1930), courtesy dr Werner Jerke

CL: Do You collect the works of young artists as well?

WJ: Yes, of course. Many of them are my friends who I invite frequently to my house. They’re often my guests.

Nevertheless, even if I’m socializing with them I always buy their works via galleries. I have never tried to omit the galleries and buy directly from the artists. It would probably be cheaper but I think that every collector should support the galleries. After all, such gallery owners introduce an artist to the art market and promote him in an appropriate way. They just merit to be supported. Thanks to their galleries, many artists have an opportunity to present themselves and the collectors can find them. A young artist doesn’t have a chance to present his works on such events like the Art Cologne or the Art Basel and this is the point where the galleries play their role – they introduce him to the art world. I think that it’s not fair if a collector buys directly from an artist. I always buy in the galleries.

Paweł Książek, courtesy Dr Werner Jerke

CL: I heard about an interesting idea that You cooperate with the young creators by mixing two passions – wine and art, is that true?

WJ: Yes, indeed, I have such a hobby of mine. I’m an owner of two vineyards where the wine is produced (editor’s note: the vineyard is being managed according to the strict rules of the wine culture. Since 1994, it’s an annual leader on the list of German 100 best wines, member of “VDP Prädikatsweingüter”, the oldest vineyard association in the world, and winner of the “Feinschmecker Wine-Award” in 2011 as “the best collection of the year”).

The labels / covers of bottles of the particular vintage are designed by Polish artists. In the previous year the labels were designed by Sławek Elsner and this year by Zbyszek Rogalski. Two bottles were even put up for auction. One, here in Germany, and another one in Poland in the Auction House Agra-Art.

CL: Where did this idea come from?

WJ: It’s actually the Rotschilds’ idea which pleased me. They also have the wine labels designed by artists, for example by Picasso, Miró, Chagall, Braque, Warhol, Bacon, Balthus (editor’s note: in 2012 Jeff Koons was invited to cooperation). So I thought: why not doing the same but with the Polish artists?

“Edition Jerke” Pinot Noir 2011, Weinzer Kreuzberg, courtesy Dr Werner Jerke, Konrad Szukalski form Agra-Art Auction House

CL: You said that You buy mainly via galleries, but is it really the only way?

WJ: I happen to buy in auction houses, usually the works of deceased artists who do not have their own galleries. Actually, I was purchasing at auctions at the beginning of my art adventure. I buy about 90% of works in Poland but I happen to buy abroad, for example here in Germany. The art market in Poland is different from the German one. For example, the auction houses in Poland have different character than their western equivalents which are focused mainly on auctions while the Polish auction houses are also galleries where you can purchase the paintings without an auction. It’s not a bad idea.

CL: When You started collecting, how did you select the works? Were You asking for advice and support or were You following your instincts and preferences?

WJ: Often, the galleries suggest me some artist but if he doesn’t appeal to my preferences I won’t buy his works no matter who tells me about his chances on the market and how good he seems to become. I’m very glad for the information shared and discussions held with the gallery owners but I don’t want somebody to persuade me to buy something. The choice is mine. However, sometimes I won’t tell that I want the works of certain artist in my collection. You can see the works of an artist mostly by visiting the galleries. If there’s only one painting out of ten I like, I choose it but this choice is very subjective. I wouldn’t explain it by the fact that this one work is good and the others are not, but it’s simply the kind of art I appreciate.

CL: Collecting, what does it mean to You? Why did collecting the art works become so important to You?

WJ: It’s kind of a sickness. If I like something I have to get it. It’s kind of an addiction – almost a disease. I had waited for some paintings for five or ten years. The collection begins only when the walls are covered with paintings. When You put the works behind the sofa or in the basement… Beforehand it’s only a decoration.

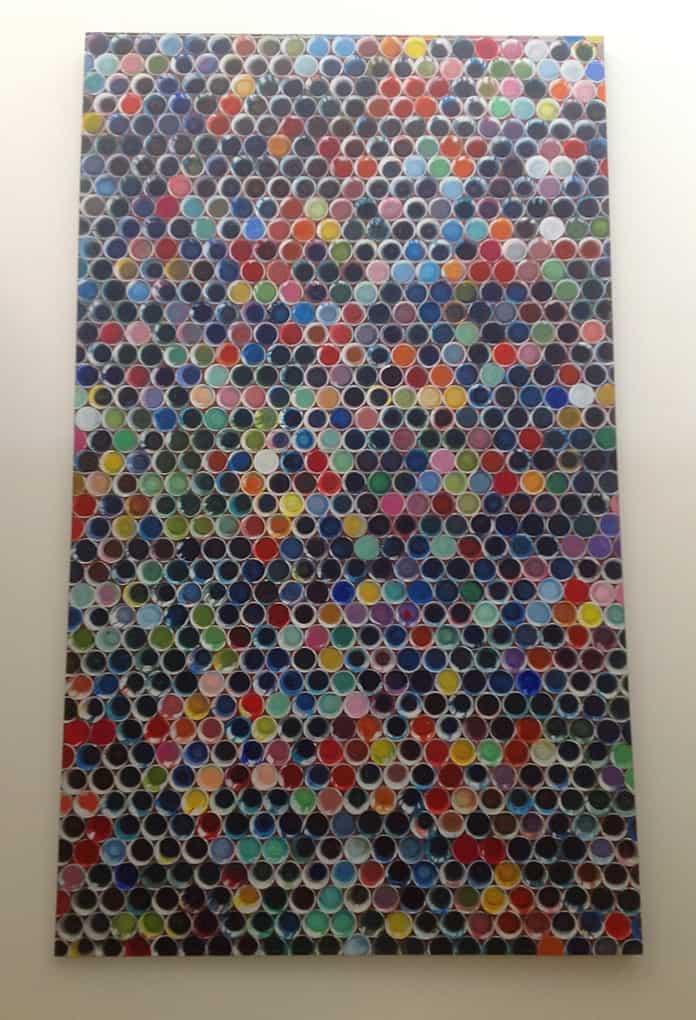

Zbigniew Rogalski, Cups, courtesy Dr Werner Jerke

CL: What is the difference between the Polish collectors and those, for example, from Germany?

WJ: The only difference I can see, but it’s nothing negative, is that the Polish collectors are focused on the Polish art. I mean, some people happen to buy the works of the western creators and sometimes the works go to different institutions but it’s not the main core of their collection. I don’t know anyone who would collect the western art.

Maybe the reason for this is the fact that the salaries of most Polish people are too low to let them afford the collection. The historical context is not without the meaning. In the western countries, for generations people were achieving wealth, houses, cars and holiday houses and then it was time to start an art collection. In Poland, it was only since the 90s when people could enjoy the benefits of a free market and as a result the society needed at first place to fulfill its basic needs and then to collect the art. There’s nothing extraordinary in it.

CL: Do You collect the paintings of foreign artists?

WJ: Yes, I do. I collect the paintings of the German avant-garde artists from the 20s and 30s. Maybe in the future I will manage to create a small comparative exhibition of the Polish and German avant-garde. I would like to complete this part of the Polish art collection with the German art and present it to the audience. The Polish and German cultures have a lot in common. The only difference is language but the art is very similar. Even our cuisines and food preferences are pretty similar. Come to think of it, which other two countries in Europe have so similar cuisines? Lots of people do not appreciate the intercultural connections between these two nations. Certainly, the history didn’t spare bad circumstances in the relations between them but for instance Szczecin is an example of how the Polish culture and Polish city affect the German area. In the surroundings of Szczecin, on the German side, there is no other bigger city. And that’s why I started wondering: why shouldn’t the Polish art museum be created in the Ruhr district? The one third of the society living here has Polish origins. It has begun in the end of XIXth century when a lot of people came here from Masuria to work in the mines. I moved from Silesia. Before the war, the football team in Schalke was composed only of Poles, and this is one of the most important teams. Schalke is situated in a distance of 10 km from Recklinhausen. The Polish culture suits here.

CL: You collect the Polish art in Germany and now You create there the Polish Art Museum. What is the reception of this art in Germany? What is people’s reaction when You tell them about national artists?

WJ: The reception is really positive. Few days before I bought the building and started telling people that I would build there the Museum I had met the mayor and few other persons who were delighted with this Polish art idea and they declared themselves to support me as much as they can. Some articles about my project were already published in the local press. In my medical practice, almost every day I talk with my patients about it. They ask questions, discuss and express their opinion that it’s a brilliant idea to introduce the Polish art here in Germany. This warm reception astonished me. Initially I thought that if anyone criticized me it would be all right but I didn’t expect such a positive attitude. Of course, not everyone knows the Polish artists but really – who (without studying the history of art) could know Władysław Strzemiński or Katarzyna Kobro fifteen or even twenty years ago? Germans need to be educated in the field of Polish art. Of course for those who study art these names aren’t unfamiliar. Everyone heard of Wilhelm Sasnal but I’d like to expand this knowledge. For the exhibition of Szapocznikov in New York I took twelve people from Recklinhausen. People are curious but firstly you have to show them something.

Wilhelm Sasnal, Magnetowid (Video Recorder), courtesy Dr Werner Jerke

CL: What about the Polish artists on the German market?

WJ: They still play there a marginal role. Our auction houses in Germany don’t resemble those in USA or in England. Some artists appear on the market but usually it’s an incidental phenomenon. It’s an art dating from different time periods. In Munich you can often find the works of the artists from the Munich school. The widest category of paintings that are being sold in Germany include works of Kossak and Brandt. In Berlin you could already buy paintings of Roman Opałka and Sasnal.

CL: Who buys the Polish art in Germany?

WJ: It depends. On the one hand, Poles living in Germany, and on the other hand – Germans. Some of my friends buy the art works, but it’s still not so much. My daughters started collecting also. The elder one started with Kossak’s painting and she has recently bought the work of Sławek Elsner.

You can distinguish three categories of persons who buy: Germans, Germans with Polish origins and Poles (in one third) who come specially for the auctions.

CL: Do You think there is a „demand” or rather an interest in the Polish art in western countries?

WJ: Yes, there’s a demand. However, it’s also time to educate people. Anyone who didn’t hear about them wouldn’t buy their works.

CL: Your Museum will be a great example of a place for such activity…

WJ: It won’t be very big but if somebody follows my example and observe it elsewhere, maybe he will join this project. This is the only way to show the Polish art and there’s a lot to do about it.

CL: What should be another milestone in the Polish art market to get out of this niche?

WJ: I think that probably the only problem is making the art export more and more difficult. In my opinion, the government should help the art market in that matter. Unfortunately people are afraid of buying in Poland because they wonder how they will take their newly purchased goods abroad. The export procedures are very complicated but this problem may still be solved so that foreigners could buy on auctions and in galleries in Poland. However, when I talk with different people I often hear a statement: “But if I bought something, I couldn’t take it out of the country”.

CL: Thank you and we will keep our fingers crossed for Your Museum!

Translation: Katarzyna Przybyś