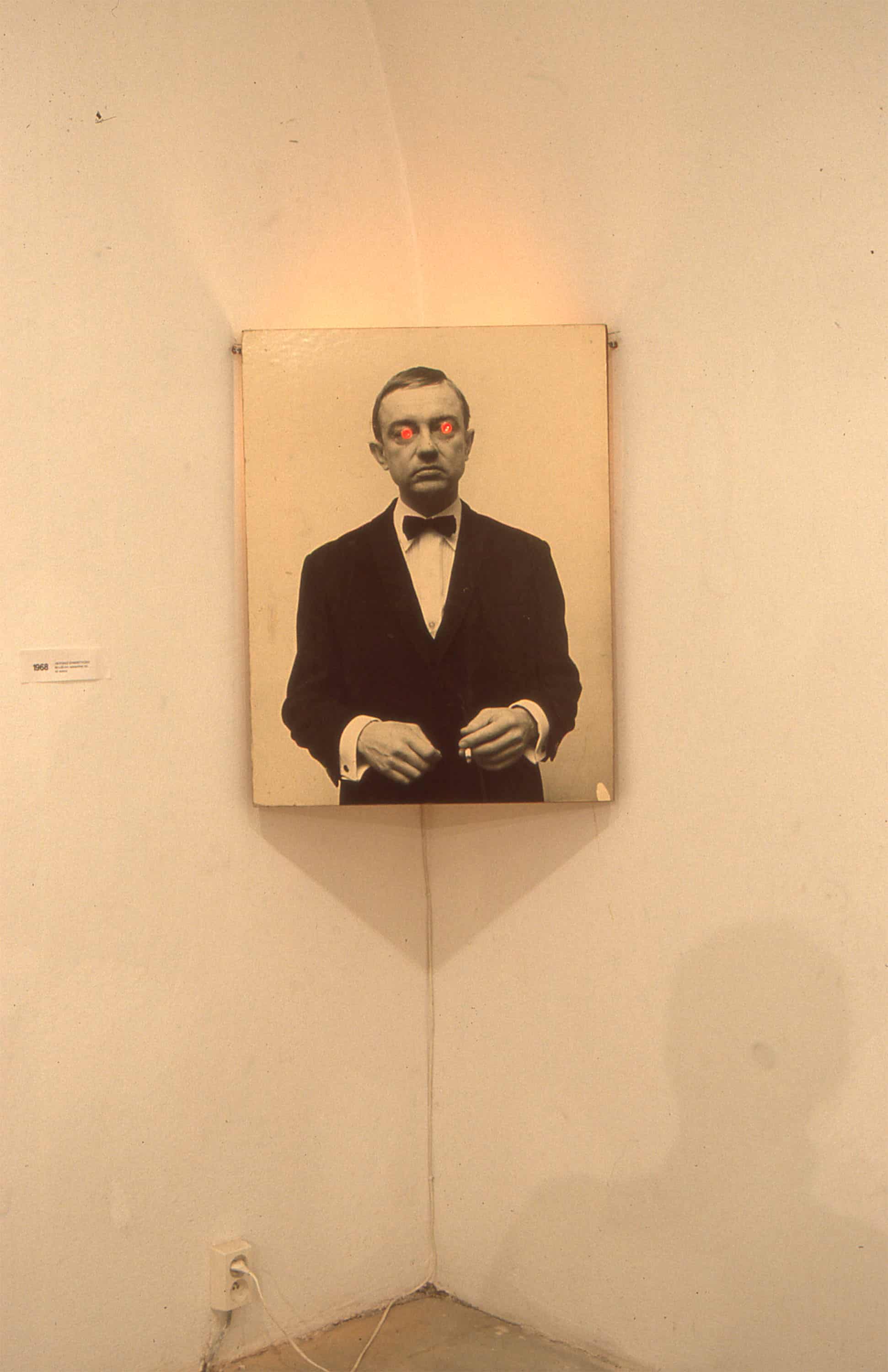

[…] I met Włodzimierz Borowski in 1968, when he was showing his action/exhibition at the Odnowa Gallery in Poznań. That was the Eighth Syncretic Show entitled Sensitization to Colour. In the three rooms of the gallery there were sheets of daily newspapers scattered on the floor; standing around or suspended on ropes there were the open crates of Threadoids, while in the corners of each interior one could find large, black-and-white photographs showing the author. During the preview, the artist, dressed as in the photographs (in a dinner jacket, white shirt and black bowtie) used an electric drill on each of his likenesses in turn, boring holes where the eyes were, until a coloured light showed through (blue, red, and then yellow). The drilling proceeded to the accompaniment of tape-recorded, piercing cry of pain that morphed into the sounds of a military march. Even though five decades have passed since that event, I remember every detail and can hear the shriek. It was a poignant, extraordinarily personal statement about art, about the status and the role of the artist, and—as it soon turned out—about the real world. The preview took place on March 6th, 1968. Two days later, the premises of the University of Warsaw saw a rally of several thousand people protesting against a number of students having been expelled. The demonstration was brutally suppressed by the police forces and militias of the so-called worker activists. This was the beginning of a wave protests that soon swept the country. On the day of the first riots, party newspapers in Poznań published a vitriolic review which denigrated artistic value of Borowski’s action. Quite readily (though not necessarily as the author wished), Sensitization to Colour was linked to what was happening in the streets. The gallery started facing problems and a year later, following Andrzej Matuszewski’s happening entitled Proceeding, the regional party authorities ordered the venue closed down.

Włodzimierz Borowski’s portrait from Syncretic Show VIII, reconstruction, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art.

I invited Borowski to participate in Sieć (net), and we began to meet regularly, either at my place in Poznań, or at his in Brwinów. We became friends. We would also see each other at various symposia and crypto-open-air sessions, which offered a pretext to exchange ideas and views with artists and theorists from outside the official art mainstream.

[…] For reasons that were more political than artistic, during the period of the martial law Borowski demonstrated contempt of the official galleries, just as many other artists. Though a non-believer, he would solidarily participate in a number of exhibitions organized at the time in Warsaw churches. He would refrain from becoming involved in current politics but, as a permanent rebel, responded to the restrictions imposed by the then political system on ethical grounds. Towards the end of the 1970s, he made the basement of his house available for clandestine printing of leaflets of the Workers’ Defence Committee; when the martial law had been introduced, he sheltered a member of the opposition wanted by the Security Service. He saw it as something obvious and never mentioned it, even though we spoke often, also—as it inevitably happened—about politics.

the latest catalogue published by Fundacja 9/11 Art. Space: “Włodzimierz Borowski. So what? Nothing. Exactly.”

[…] Akumulatory 2 Gallery in Poznań saw three of Borowski’s solo exhibitions. In 1977, he came there with Black, a piece which deliberately drew on the show from twelve years ago at the Symposium of Artists and Scientists in Puławy. The show in question had featured mathematical symbols “+” and “–” fashioned from mirrors, and a styrofoam “0” between them, which soon crumbled to pieces. At the Akumulatory, there were ten sheets of white paper inscribed with short texts, hanging around in space. Handwritten by the artist, the verbal metaphors referred to things, notions, and colours, leading gradually to a large black surface painted on the wall. In his preview speech, the artist elucidated on the links between that work and the idea underlying the piece in Puławy. A year later, during the collective show Private Views (also at the Akumulatory), he supplemented Black with new elements: five, likewise handwritten, pages of White.

the latest catalogue published by Fundacja 9/11 Art. Space: “Włodzimierz Borowski. So what? Nothing. Exactly.”

In 1981 Borowski presented The Cataract, a kind of reserved installation consisting of nine white plaques with a repeating, template-like drawing of an eye. The same motif appeared on three, somewhat larger pieces of hardboard. The difference was that in the latter there were words inserted into the contours of the eye: “nos [nose]” on two of them, and “katarakta [cataract]” on one. By disrupting the order of the white plaques, they changed their semantic status and caused confusion. Also, in front of each set of plaques hanging on three walls at the gallery, there stood an ashtray with draped, artificial flowers that had been sprayed with perfume. In later exhibitions, the work was displayed on single wall, with the flower ashtray placed centrally before it.

The following exhibition at the Akumulatory, To See or to Hear (1984) comprised two, seemingly distinct pieces. The first was a series of eight pictures—loose, frameless rectangles of grey, unprimed canvas. On the margins of each, one could see multiple iterations of “I was”, written in small letters. Only on some could one discern the enigmatic traces of what (inadvertently?) happened or might have happened. They were hung on the wall in one row, evenly spaced. The second piece featured three drawings with two commentaries, also executed on loose, unprimed canvases. The work had a separate title: Triptych with Gaps. The drawing on the right had been made by the artist’s wife, Grażyna, while the one on the left was created by Weronika, their 4.5-year-old daughter, both of whom did it blindfolded. The canvas in the centre bore the imprints of paws of their favourite dachshund, Rols. The artist reduced his contribution to authorizing/filling in the 40-centimetre gaps between the sections of the triptych. To dispel any doubt, he confirmed it with an inscription in the corners of the drawings.

Włodzimierz Borowski, Arton-AM2 (Arton VIII, Arton Manilus), assemblage, 49x32x16-cm, a private collection.

Borowski increasingly reduced material reifications of his ideas in favour of notional elocutions. More and more often, he would play with words, written or spoken, while collaboration with others gave him a sense that the scope of his own artistic freedom expanded. Therefore, his projects grew ephemeral and were delivered only once, including Nine Times If or What-Iffings (piece for once voice and two kettledrums), The Raven’s Day and In the Second Month After the Raven’s Day (featuring Janusz Bałdyga), Ethical Parsing (featuring Piotr Bikont) or Pedagogical Table Poem.

When in 1992 an opportunity presented itself to organize a comprehensive retrospective of Borowski’s work at the Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, I hoped it would serve to verify the often myth-based, incontrovertible canons of contemporary history of Polish art. Włodek was sceptical of my proposal, but was ultimately won over to the idea. Consequently, Traces 1956–1992 showed all available works of the artist, including some which had never been displayed in Poland, as well as reconstructions of pieces that had been destroyed. The exhibition made a tremendous impression, and drew numerous viewers every day. The extensive bilingual catalogue which accompanied the show included a text by Jerzy Ludwiński, original texts by Borowski, a substantial amount of reproductions and a detailed biographical note. A number of enthusiastic reviews were published, too; after Warsaw, the exhibition toured to Sopot, Wrocław and Lublin, where it enjoyed considerable interest as well. But that was as far as it went. No entrenched art-and-history canons were undermined.

‘Włodzimierz Borowski’ – exhibition catalogue, Contemporary Gallery, Warsaw.

Among the works shown at the Centre was Borowski’s latest: a monumental, four-part, colour assemblage entitled So What? Each part consisted of three integrated, oval elements, each covered by different, evenly laid colour. To these colourful surfaces the artist affixed varied configurations of simple tools: hammers, pincers, wood saws. Most likely, it was with those tools that he had made the work. They did not symbolize anything, they were no metaphor. They were complemented by slapdash words in white paint: “so what?”, “nothing” and “exactly”. I believe that after the experience of reduction of the artistic self in Triptych with Gaps, that was Borowski’s final farewell to objectified art, to any kind of materiality of the work, to the mythology of the artist-demiurge.

[…] He died in 2008. A year later 13 banners were hung in the park in front to the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, inscribed with artistic catchphrases-mottos relating to current ideas in art. And among them, there was a quote from Włodzimierz Borowski: “the work of art is a trace, a husk of what has been discovered.”

Włodzimierz Borowski’ book titled ‘Est-Etyka’

Written by Jarosław Kozłowski

The abstract from the latest catalogue published by Fundacja 9/11 Art. Space: “Włodzimierz Borowski. So what? Nothing. Exactly.”

The project was co-financed by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage from the Culture Promotion Fund. Co-financed by the City of Poznań.