Pre-internet age…

Polish culture has had little bearing on the global landscape, contributions of selected artists notwithstanding. Certain events were often propelled forward due to those artist’s own projects. Rarely do these kinds of bold artistic statements emerge amidst the socio-political turmoil of today’s Poland. In my extensive artistic career, I have had a chance to witness at least two such monumental events in the early 1980s – INFERMENTAL and Konstrukcja w Procesie (Construction in Process). Since the latter project has already received recognition, allow me to take its predecessor under close scrutiny. INFERMENTAL was an international art project launched in Budapest in 1980. The Internet did not exist, yet the need to establish a global cultural network was palpable. The introduction of fax and mail art fell short of expectations. One should bear in mind that Poland was then the only country steeped in a sense of freedom owing to the efforts of the Trade Union “Solidarność” and its proponents. For others, Poland was the beacon of hope.

Several members of the Warsztat Formy Filmowej (Workshop of the Film Form) arrive in Budapest at the invitation of the Centre for Polish Culture to present their multimedia works of art – Małgorzata Potocka, Paweł Kwiek, Ryszard Waśko and yours truly (Józef Robakowski). We are taken aback by the great turnout; there are over 500 people in the audience. There is a film screening which includes highly analytic pieces of cinema, as well as films about art. We engage in seminal debates: why do we enjoy so much liberty, how do we stay so optimistic? The following night, we meet Dóra Maurer, an outstanding Hungarian artist, Gábor Bódy, a filmmaker we are already familiar with, and Veruschka (his wife). They put forward the exceptional idea of INFERMENTAL, an international communication platform of the avant-garde movement. The original concept belongs to Gábor Bódy. We sign the treaty heralding a close collaboration. Our discussions indicate that we would create the very first international magazine on videocassettes, the most popular networking system on the planet. The material submitted for the given issue would be curated in several different cities. Initially we opt for Vancouver, Tokyo, Paris, London, Cologne, Vienna, Budapest and Łódź. It is worth mentioning that Gábor Bódy receives a lavish DAAD Scholarship in the West Berlin around the same period of time. Thus, we obtain the shoestring budget indispensable for setting things in motion. My video “Żywa Galeria” (Living Gallery, 1975) becomes the epitome of the module. Five minutes to showcase the offered material on a vast array of subjects featuring documentations, clips, video and film excerpts, photography in every form imaginable, interviews, reviews of conferences and other cultural events. You relinquish copyrights by submitting your work. Turning a profit on the material is not an option. The principle dates back to the 1970s and the activity of the Warsztat Formy Filmowej. Unfortunately, the inaugural magazine produced in Budapest is issued under Poland’s martial law. INFERMENTAL fulfills its role, nonetheless. Miklós Novottny, a student of the Łódź Film School born in Hungary, avoids being searched at the border. He is the one who smuggles the VHS tapes with recordings from all over the world to Łódź and Budapest. Materials collected for the following edition are curated by Małgorzata Potocka who leaves for Budapest. My passport has been revoked for years already. In the Exchange Gallery, we use two VHS players to copy the tapes delivered by Novottny and proceed to circulate them around Poland. INFERMENTAL provides us with insight into the latest tendencies in the global culture and avant-garde movement. In my opinion, this significant project initiated by a group of ordinary artists from the so-called Eastern Block should forever go down in the history of art.

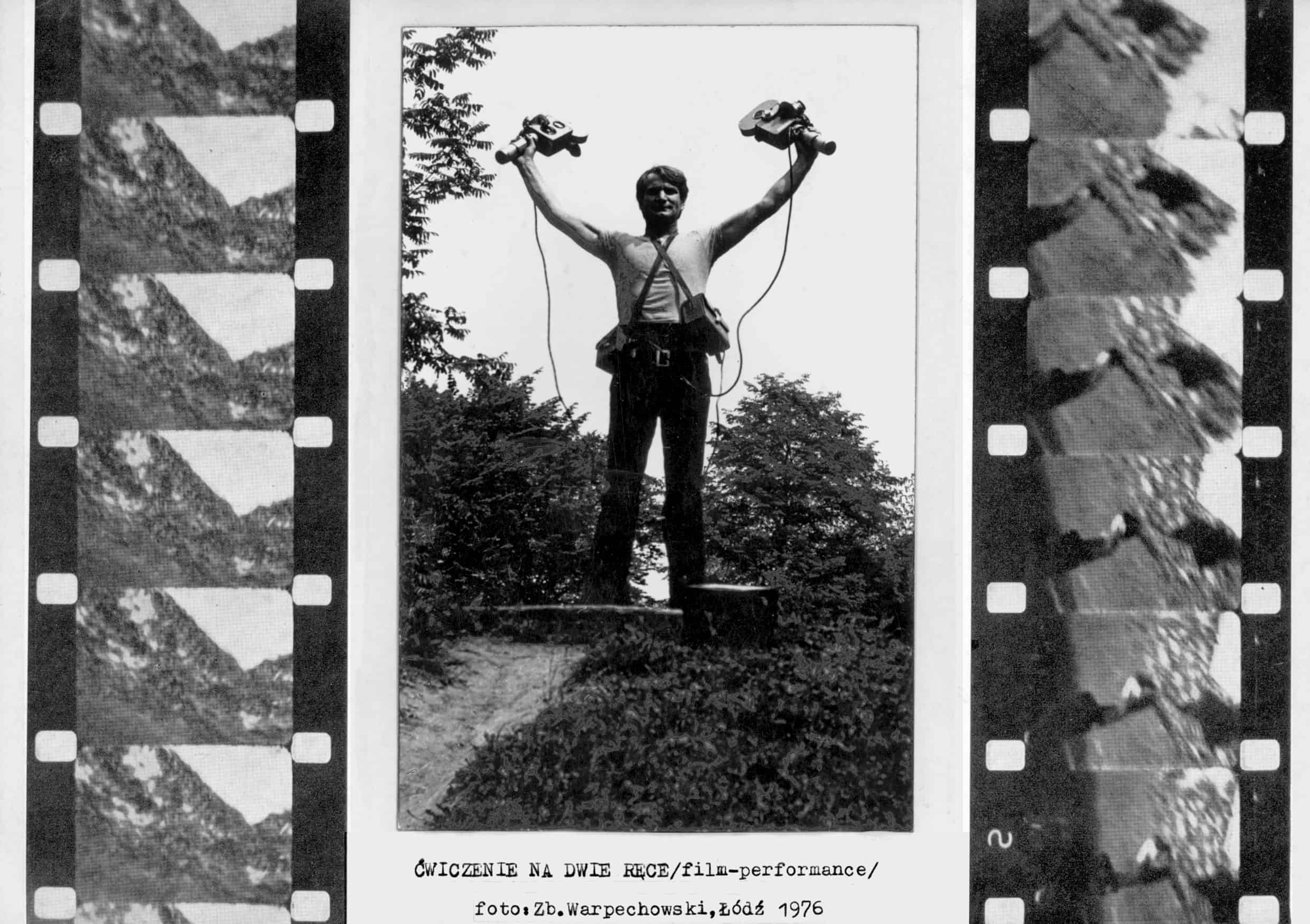

Józef Robakowski, “Exercise for Two Hands,” filmed action, 1976 (operator: Zbigniew Warpechowski), courtesy of the Exchange Gallery

Ways of seeing/looking. The origins…

The way of seeing I proposed was borrowed to some extent from tradition. This historic milestone was viewed by my generation in terms of Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński’s raid over the art scene in Łódź. Faced with an exponentially oppressive socialist realism, the pair of Soviet artists relocated to Poland in search of artistic freedom. This period of national convalescence was marked by the predominant Neo-Romanticism, a creative exploration drawing on the experiences of Expressionism or Futurism. Dadaists were scarce. Though artistically prolific, Witkacy disassociated himself from the tradition of Dadaism. Kobro and Strzemiński introduced something unprecedented to the Polish art scene. In his extreme manifesto on Unism in painting, Strzemiński purports the existence of painting enclosed by a frame which can assume the form of a timeless unified plane. His convention rejects any sort of expressionistic tension. While the principles of Constructivism are firmly cast aside, his “unist painting” manages to retain its organic quality. A new definition of sculpture devised by Kobro establishes its connection with the space. Her “spatial compositions” organize movement. This underlying assumption demonstrates a remarkable affinity with urban planning. Kobro’s theory stays relevant. Her notions are held in high regard by numerous contemporary artists. For this reason, Strzemiński and Kobro’s daughter and I decided to establish the Katarzyna Kobro Award in 2001. This prestigious distinction conferred upon ingenious artists seeking unconventional conceptual solutions is handed out annually under the auspices of the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź by a group of artists selected by a curator, who is also an artist. Katarzyna Kobro was an artist of great pride. In the 1937 survey conducted by the magazine Głos Plastyków, she made a statement in favor of international exchange, reproached Stanisław Szukalski, a sculptor, for his nationalist and fascist tendencies and alluded to the circle of extraordinary artists from the Western Europe, such as Vantongerloo, Arp and Brâncuși. A paper on spatial compositions delivered during a seminar by Janusz Zagrodzki, a fellow third-year student of museology at Toruń University, sparks my interest in the exceptional art practice of Katarzyna Kobro. After I’d graduated from film school, Janusz and I made the experimental film dedicated to her oeuvre (1971). The Workshop of the Film Form drawing on the analytic achievements of Kobro and Strzemiński is established in the year 1970. The animated video entitled “Rynek” (“Market”), which I shot in collaboration with my colleagues, Tadeusz Junak and Ryszard Meissner, is the very first film production of the Workshop. We adopt a strict rule, the film is to be recorded with a time-lapse camera at the rate of two frames per five seconds. We sit on a rooftop of a very tall building by the so-called “red market” in Łódź and observe. An entire day’s footage is captured in just under four minutes. We examine various events which occurred in the enormous square at an accelerated pace. As a result, we arrive at the conclusion that we can transcend the limits of human imagination thanks to the apparatus. No other director is remotely capable of constructing this type of “reality.” Many of us, guys previously focused on technicalities, ventured into the exploration of reality throughout the 1970s. Another incident aimed at penetrating the so-called “natural reality” was an artistic action performed on the same location in autumn. The square is still empty at four in the morning. We unload tons of stuff that we procured from my dead aunt’s spacious apartment on Piotrkowska Street. The level of decay varies, yet most objects are still fit for use (chairs, mattresses, utensils, mirrors, closets, plates, cans…). We arrange them at the market stall situated right in the middle of the square, in close proximity to the walls of a public bathroom. Wacław Antczak, a tailor/artist and a proud representative of the shabby proletariat, is appointed as the salesman while we, the artists from the Workshop of the Film Form, decide to stay undercover. We play the mob that has gathered in front of Wacław Antczak’s market stall. Valuable possessions of my aunt are sold at a great bargain: a closet – PLN 20.00, couch – PLN 15.00, two chairs – PLN 10.00 etc. etc.…Antczak leaves his post at noon to take a leak. The objects he left unguarded are looted in fifteen minutes. This anonymous “penetration of reality” represents the antithesis to the artistic conventions of theatre proposed by Tadeusz Kantor and Józef Szajna, which both assign the role of an oppressive principle to the director. A similar action was performed in the Piotrkowska Street by Andrzej Barański, the now legendary film director. Random passers-by were asked by a cameraman to recite the following lines from “Ode to Youth” by Adam Mickiewicz. Consequently, a unique joint interpretation of the poem was offered to a number of participants. Those public artistic gambits were meant to probe and expand the notion of cinema to include a perspective extraneous to the director. The Workshop of the Film Form gained international acclaim due to our countless inquiries. Numerous films we produced have paved the way for so-called expanded cinema.

Józef Robakowski, “Market,” video, 1970, collaboration: Tadeusz Junak, Ryszard Meissner, WFF, courtesy of the Exchange Gallery

Testing and expanding the notion of cinema…

Art appeared in my life almost organically, a gesture spurred by yearning for freedom. In spite of the hardships I might face these days, I always try to find a place for myself, as well as other fellow artists. Nowadays I often dive into the cultural space of the Internet, scrolling through Facebook for instance, and hoping to come across some snippets of thought indicative of a multitude of shifts in people’s minds. The human mind is a vast and intricate notion. Therein often lie the origins of art. Among other things, it is “the online reality” viewed as an actual transmission channel for many people’s convictions that underscores my pieces. In that sense, creativity goes way beyond my own imagination, ignites my relentless efforts to “decipher” the cognitive material code of e.g. Facebook, which acts as the storage for ideas conjured up by scores of contemporary artists and culture figures. I gallivant around the Internet in search of inspiring issues raised by other users. I am the collector who often alters the context of their original meaning. As someone else fuels my creativity, I experience moments of happiness. It was also the case when we were shooting my seminal art film entitled “Living Gallery.” I yielded “the creative aspect of filmmaking” to a group of new media artists. They all were granted a complete liberty and a 1:30 minute film slot to present their own artistic endeavors. My role as a producer was to provide them with limitless possibilities. Bearing witness to the “live” expansion of the very notion of cinema brought me immense satisfaction. Interestingly, a couple of those twenty artists struggled with the medium itself. Time factor is of paramount importance for filmmaking. Pacing builds a sense of reality. I once had a debate with the marvelous Jerzy Bereś who showed me his 30-minute “manifestation” at Krzysztofory Gallery. After the shooting was done, I asked him how he planned to abide by the one unbreakable rule (1:30 minutes). “You are the director, Józef. You count the time,” he snapped back. Touché. I am eternally grateful for his masterful riposte. On the other hand, Ryszard Winiarski was much more methodical in his actions. He ensconced himself in an animation studio and filmed his feature in a painstaking manner. A disparity in these two approaches testifies to the merits of celluloid testing. It was indeed a test for the artists willing to partake in such a risky project, as well as for the director himself who collaborated with those following their instincts and therefore broadened his own horizons.

First signs of freedom…

In the socialist era, my artist friends and I focused on carving out our niche. The art we produced as students was deliberately detached from the tentacles of the national administration and artists’ associations. Naturally we also availed ourselves of ZSP funding and opportunities provided by public universities. For instance, a student research club was established by members of the Workshop of the Film Form. Art groups enabled us to engage in extracurricular creative activities. In Toruń, we founded the artistic film club STKF “Pętla,”, as well as an art group dedicated to photography called Zero-61. At times, we had no recourse other than to organize exhibitions and film screenings with the financial support of the Polish Students’ Association (ZSP), which dealt with a broadly understood development of culture. On the other hand the Socialist Youth Union (ZMS) and the Rural Youth Union (ZMW) both had extreme political agendas in line with the socialist policy. I was never even remotely interested in these organizations. In the 1960s we managed to establish independent associations untarnished by suggestions of the party. So-called socialist art has never been produced by any member of Zero-61, STKF “Pętla” or the Workshop of the Film Form. It’s a phenomenal statement. We also steered clear of blatantly political events. We cynically boycotted art-related events such as the famous socialist demonstration on the Poniatowski bridge, the Palace of Culture and Science, as well as outdoor cultural workshops headlined by ZMS. The rise of new media art was precipitated by our organization of not only the huge festival of photography, but also two editions of a film festival held in Toruń (1960s). In the 1970s, this movement contributed to the emergence of expanded cinema and the opening of an abundance of exhibits featuring analytical and conceptual photography. Performance, intuitive music and independent theatre keep thriving. Private publishing houses appear on the scene. A multitude of art galleries with their own programs opens their doors. Alternative workshops and joint gatherings of artists, critics and art historians take place in nature. We ostentatiously manifest our “freedom” by organizing private tours around Western countries to forge a vigorous connection with artists from all over the world. Additionally, we eagerly tap into the possibilities of the exchange of ideas offered by fax machines, mail art and the international art magazine INFERMENTAL.

Józef Robakowski, “The Sale of Furniture,” public action in the market square in Łódź, 1971 (photo by Janusz Połom), courtesy of the Exchange Gallery

Gdańsk, that was it…

The year is 1959. Gdańsk is the cultural hub holding more artistic events than any other city, including Krakow. I lived in the district of Wrzeszcz and attended the Vocational Teacher Training Institute because I got rejected by my beloved Film School. Around that time, hordes of then modern artists popped up in Gdańsk, our student club “Żak” especially: Kobiela, Cybulski, Wajda, Polański, Gruza, Bielicki, Federowicz, Alina and Jerzy Afansjew, Hajdun, Krechowicz, Tuszyńska (a beauty) and Kępińska (a demon), Chyła, Morgenstern and many, many others. When I was a student I met Jerzy Wardak, an outstanding photographer who studied under the true masters of the camera – Edmund and Bolesława Zdanowski. Personally I would often stop by the club whose film section was overseen my friend, Lucjan Bokiniec. He often boasted how he succeeded in luring the great Norman McLaren to Gdańsk, who agreed to present a fantastic screening of his experimental films. I bought an amateur camera Admira 8 and started making my first “important” films. On Sundays I explored the medium of photography by accompanying Wardak to his weekly creative workshops. I used to listen to music in the iconic club “Rudy Kot” located near “Żak.” The early concerts of the Belarussian repatriate Niemen Wydrzycki (Niemen, in short) are still etched in my memory. To me, he was an older gentlemen playing the classic accordion and singing the classic Spanish tune called “Granada” amid the concerts. Although his voice was truly impressive, some audience members were still shouting “Off the stage, grandpa!” during his performances. In retrospect, Czesław Niemen is an absolute music legend whom I respect greatly, especially for the concert he gave alongside Józef Skrzek in Helsinki (1973). What is also worth pointing out is the fact that the performance hasn’t been forgotten due to the professional film recording provided by the top-notch Finnish crew.

Them, the capitalists…

A huge international meeting aimed at bringing together the artistic community from the East and the West was orchestrated in the famous De Apple Gallery in 1978. Amsterdam was flooded by artists from New York, London, Paris, as well as Hungary, Czech Republic, Poland and Yugoslavia. We had the pleasure of the company of Ulay and Abramovich herself, who used to live in the Netherlands at some point. If it wasn’t for the “utilitarian” quality of friendships forged during these creatively inspiring meetings, I would’ve never stood a chance of actually implementing “Construction in Process” (1981) – the largest cross-cultural artistic initiative in the Eastern Europe. Over fifty artists, museum directors and curators were invited to Łódź. Even though all these renown guests had to travel on their own dime, they yearned to experience first-hand the surge of the liberation movement in the Soviet nation that had already been initiated by members of the Trade Union “Solidarność.” Perhaps for the very first time ever, the artists of the West confronted with the spartan conditions of art production were transformed into so-called art workers, as Gerard Kwiatkowski from EL Gallery liked to say. The majority of artists from abroad were eager to change into working suits, which we had enjoyed wearing on a regular basis. Then very popular quilted jackets added a flair of sophistication to our ensembles. In the evenings, we gravitated in our droves towards typical pubs in Łódź. One toast after another, we cemented our artistic life-long comradery with no strings attached. One after another, we thanked Ryszard Waśko, the curator of this excellent international exhibit, for coming up with the great idea.

New media artists from the Workshop of the Film Form, Łódź 1973, courtesy of the Exchange Gallery

We boycotted them, they boycotted us…

The El Gallery was established by Gerard Kwiatkowski in the immense Post-German church situated in Elbląg. This new media center of sorts soon achieved the status of an art sanctuary. Every stay in this “holy” space delivered a wealth of unique experiences. During “Akcja Warsztat” (the Workshop Action) staged in the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź (1973), Kwiatkowski invited us to collaborate on the international meeting/ exhibit entitled KINOLABORATORIUM (CINEMALABORATORY) held within the framework of the 5th Art Biennale. The democratic formula of the project was unprecedented on the Polish art scene. The participants devoted the hour of their own presentation by scribbling on the blackboard which stood in front of the church/art gallery. The open space was available to a number of guests (artists). There was no official list, any person could have unveiled their piece during KINOLABORATORIUM. Visual artists, photographers, filmmakers, musicians, theatre folks, visual poets and performance artists had all assembled in Elbląg. People didn’t care about anyone’s age, wealth or professional credentials. They didn’t receive remuneration, opulent hotel rooms, awards and roaring applause. The international convention lasted five days. Its influential model had often been emulated by the avant-garde in the years to come, at least until the 1989 exhibition “Lochy Manhattanu” in Łódź (The Dungeons of Manhattan). My friends and I launched the staggering art installation. A special location was of great significance to the project. A garage under the tallest building in the local Manhattan was at our own disposal in 1989 thanks to the support of Antoni Szram, a former director of the Film Museum in Łódź. An experience of such a vast austere space was quite overwhelming in itself. As a curator, I reached out to the artists of different generations: those who in the 1980s had never engaged in any collaboration with Wojciech Jaruzelski’s administration and enthusiasts of the avant-garde. What mattered to me the most was creating a platform where young artists and the artists of the 1970s could actually meet, where they could exchange their ideas outside the rules of competition. This exchange in the times of hardship defined the value of the project. Uniting these two generations carried great weight because numerous art historians, critics and artists themselves professed the doom of their predecessors on the grounds of their ties with Polish Socialism. Ultimately, the two generations became friends during this grand meeting (at least in my opinion). They gained respect for one another. “Lochy Manhattanu” went down in history as a successful yet unorthodox endeavor. Afterwards we issued the first celluloid catalogue that perfectly conveys the atmosphere of the exhibit/ installation. You can watch the video on the official website of the Museum of Modern Art. The 1970s team included for instance Natalia LL, Bruszewski, Mitan, Winiarski, Rytka, Murak, Warpechowski, Mikołajczyk, Schaeffer…whereas the 1980s generation was represented by Gruppa, Staniszewski, Bałka, Kryszkowski, Bohdziewicz, Truszkowski, Konopka, Yach Film, among others…GARAŻ, as the stage for performances and presentations, was booming. The 1980s was the decade of sweeping demonstrations held by young artists, e.g. in Sopot. The first proper neo-expressionist exhibit featured only works by an older generation, a decision made by Ryszard Ziarkiewicz, the show’s curator. A stark divide persisted among the artists. I committed myself to bringing them all together, to spark a mutual interest. Personally I find any form of political or biological categorization entirely unacceptable. Furthermore, “Lochy Manhattanu” was the first exhibit in Poland centered on new media art and installation. While making preparations for the show, I discovered that our curators had never even used these terms in any book or catalogue. Our local critics still very much preferred presenting and discussing painting, drawing, graphic and conventional sculpture. New media art was denounced by many artists and critics. Almost the entire decade was marked by an open defiance of avant-garde artists towards the national government and authorities. We (a throng of independent artists) remained intransigent in our opposition towards the official state-endorsed events. The alternative movement was thriving, functioning outside the official structures of galleries, museums, cinema, press and television. Nowadays, it is hard to imagine that the name of someone, such as let’s say Robakowski, would be erased for an extended period of time. The national boycott was lifted only in the 1990s. For seven or eight years in the previous decade, numerous Polish artists were banished from the cultural landscape. My videos and films from that period include images recorded on a TV-set because I was unable to use my camera outside. The irony is that today I am willingly filming my computer desktop with Facebook open, yet another vibrant fascinating “reality” brought to life by yet another collection of people from various corners of the globe.

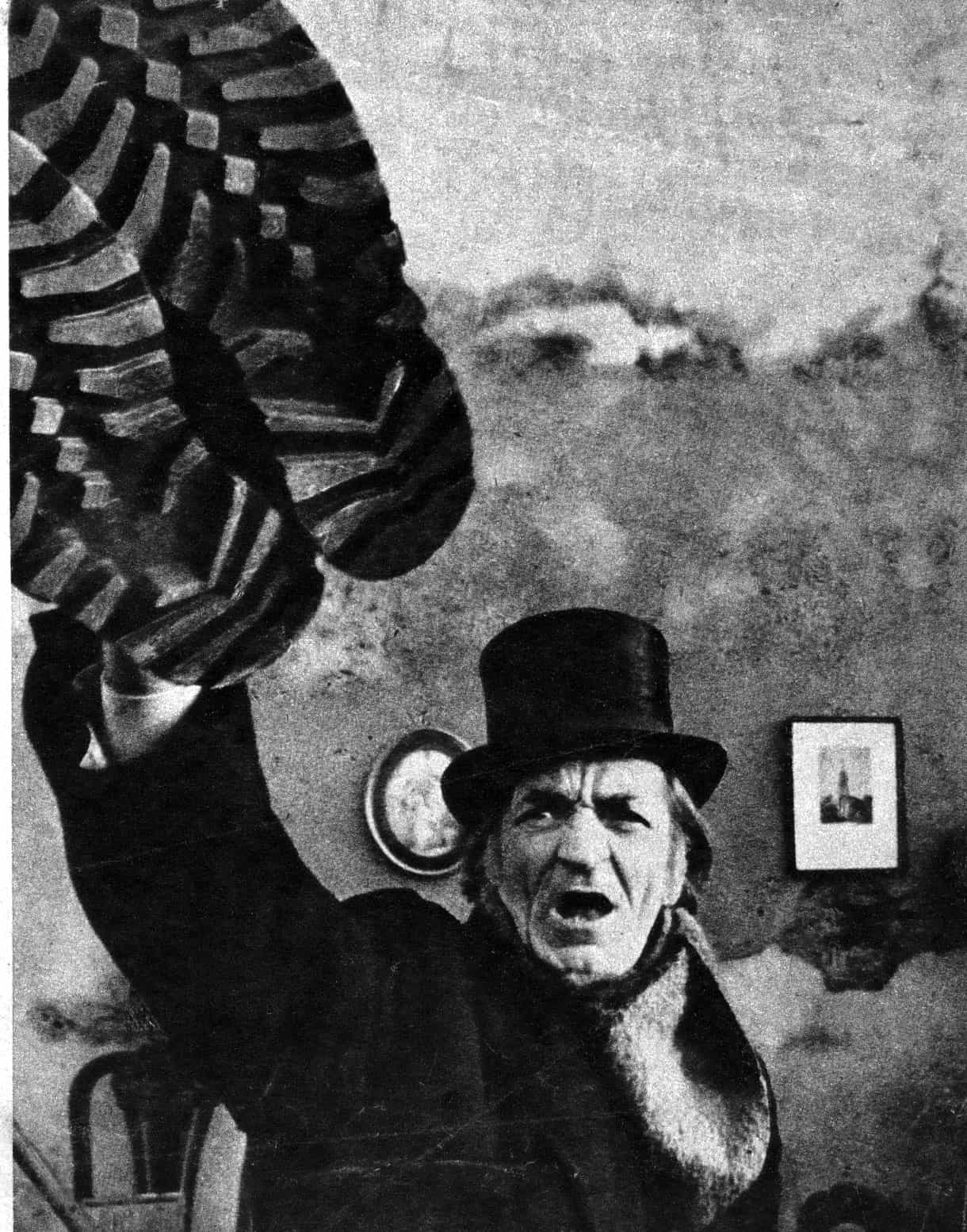

Andrzej Partum, “Avant-garde Silence,” working screenshot from “Living Gallery” by J. Robakowski, 1975, courtesy of the Exchange Gallery

A pattern of human behavior…

A large exhibition entitled “Okrutna kamera” (Vicious Camera) opened in Łódź in celebration of the end of my tenure at the Film School. In 1974, the Dean of the Acting Department asked me to film a staged scene prepared for entrance exams by other professors. Candidates are expected to “arrange” the space of a room with only a chair, widow and an ordinary hanger. The rules of the assignment are discussed with candidates beforehand. Over fifty applicants stand waiting in the atelier behind the doors leading to the set. They knock, enter and execute the assignment one after another. A turned-on camera “plays” the window. The assembled professors analyze the final results of their “arrangements” on the basis of the processed material. The name of each candidate is called prior to their entrance. I feel extremely uncomfortable watching this footage now. Here, I bear witness to a cruel trick of the academics. All pupils experience the enormous stress. As a result, they conform to schematic patterns of behavior, their movements seem unnatural. Stage fright reduces them to wooden puppets. Numerous television and film records are dedicated to this “vicious camera.” The people it captures become my characters whose status alludes to the evolution of mentality occurring in our pretty complex reality.

Films as the icons of bygone day…

Is there anything left to do for us, artists? If the goal is to become an active creator, then I choose to “immerse myself into” so-called reality, this is my arena. With that in mind, I have relinquished a number of social obligations and stopped teaching at the academy. Finally I have the freedom to produce my works however I want. I have always considered myself an advocate of “auteur cinema.” It’s the perfect position for any creative mind. My colleagues who passed away missed out on a chance to observe their achievements. However, my greater longevity allowed to me to finally realize how much I owe them. I was a member of several art groups that made valuable contributions to our culture. Together, we created “icons” – “models” even – which I believe operate seamlessly up to this day. They are indispensable for those who will come after us. Nowadays I lack the strength to rise to the task. I receive offers and refer interested parties to museum collections, to the public and private archives. The collections themselves are in a constant state of transition. For the artist can experience genuine satisfaction only if their accomplishments live on due to their merit and intrinsic mystery.

article by Karolina Kliszewska

edited by Maggie Kuzan

Józef Robakowski, “The Sale of Furniture,” public action in the market square in Łódź, 1971 (photo by Janusz Połom), courtesy of the Exchange Gallery